Data snooping is the catch-all term used to describe a misuse of data mining techniques. There are perfectly legitimate uses to data-mining, but data snooping is a big ‘no-no’ for the legitimate statistician. If the researcher does not formulate a hypothesis before looking at the data, but instead uses the data to suggest what the hypothesis should be, then he or she is data snooping.

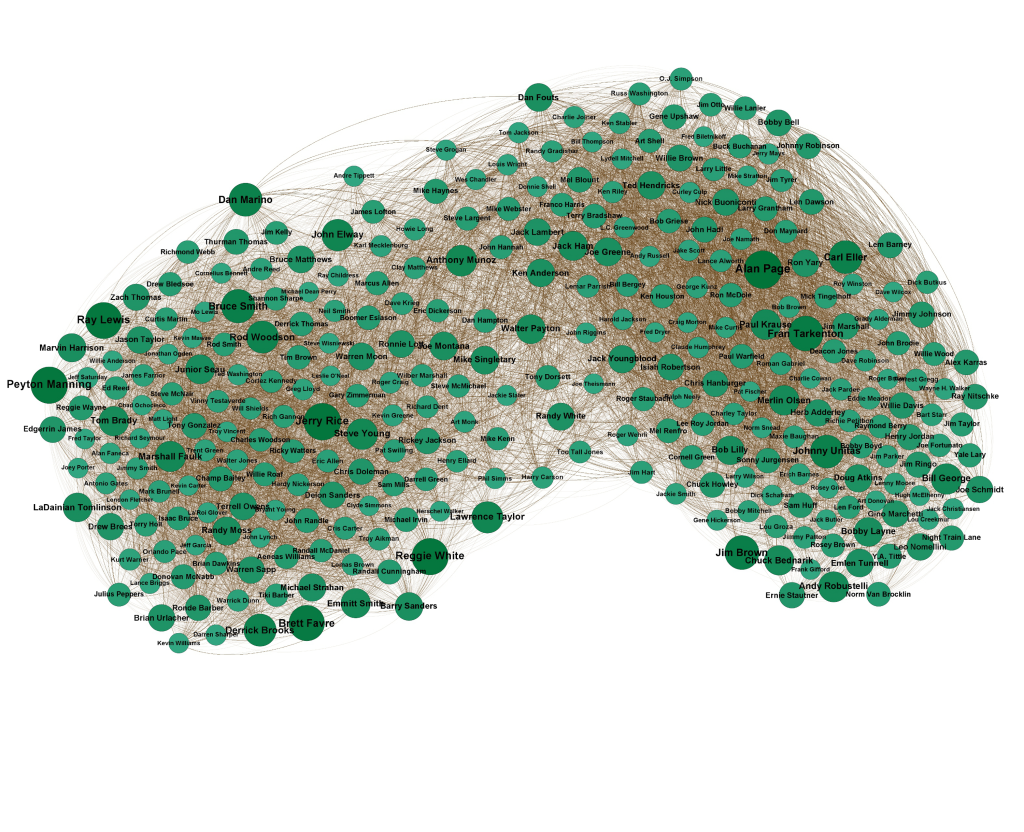

I’m guilty of data snooping, but (hopefully) only in a tongue-in-cheek fashion. When I said Reggie Wayne was much better against blue teams than other opponents, that was data snooping. We’ve all been taught that history repeats itself; that translates to “if the evidence indicates a strong relationship in the past, then it is likely to continue in the future” when it comes to statistical analysis. For example, history tells us that first round picks will perform better, on average, then sixth round picks. That’s both what the data suggest and an accurate statement.

But what happens when the data suggest that being born on February 14th or February 15th means a player is more likely to be a great quarterback? After all, the numbers tell us that 14% of all the NFL’s 31,000-yard passers were born on one of those two days, which only account for 0.6% of the days of the year. Just because history tells us that those dates are highly correlated with success — and the p-value would surely be very impressive — doesn’t mean that there is any predictive value in that piece of information.

[continue reading…]