Yesterday, I looked at coordinators who immediately left Super Bowl champions to become head coaches. Today, I expand on that study by looking at the 50 offensive/defensive coordinators on the 25 Super Bowl champions from 1992 to 2016 and tracking the remainder of their tenures. Let’s leave Josh McDaniels (2014/2016 Patriots offensive coordinator) out of the mix, since it appears as though he’s doing to be in New England for the foreseeable future. What about the other 48? When did they finally leave?

Left Immediately (7)

Charlie Weis (2004 NWE OC)

Romeo Crennel (2004 NWE DC)

Mike Martz (1999 STL OC)

Mike Shanahan (1994 SFO OC)

Ray Rhodes (1994 SFO DC)

Norv Turner (1993 DAL OC)

Dave Wannstedt (1992 DAL DC)

In this group, 5 left to become head coaches of other NFL teams, Martz was promoted to Rams HC, and Weis left to become the Notre Dame head coach.

Left After One Additional Year (14)

Matt Patricia (2016 NWE DC)

Rick Dennison (2015 DEN OC)

Wade Phillips (2015 DEN DC)

Dan Quinn (2013 SEA DC)

Jim Caldwell (2012 BAL OC)

Joe Philbin (2010 GNB OC)

Steve Spagnuolo (2007 NYG DC)

Ken Whisenhunt (2005 PIT OC)

Charlie Weis (2003 NWE OC)

Romeo Crennel (2003 NWE DC)

Marvin Lewis (2000 BAL DC)

Peter Giunta (1999 STL DC)

Butch Davis (1993 DAL DC)

Norv Turner (1992 DAL OC)

Eight of these coordinators left to become head coaches after one more season as a coordinator (Patricia, Quinn, Caldwell, Philbin, Spagnuolo, Whisenhunt, Crennel, and Turner). What about the other 6?

- Dennison and Phillips were both let go as part of the coaching change from Gary Kubiak (retired) to Vance Joseph a year after winning the Super Bowl. Both resurfaced on playoff teams in 2017 (Bills and Rams).

- Weis, as mentioned above, left to join the Fighting Irish.

- Lewis had his contract expire with the Ravens after 2001, as everyone assumed he would leave to get a head coaching job; that didn’t happen, so he had a one-year pit stop as the Redskins defensive coordinator before becoming the Bengals coach indefinitely.

- Giunta was fired after the Rams defense collapsed in 2000.

- Davis left to become the Miami Hurricanes head coach, and later, the Cleveland Browns head coach.

Left After Two Years (6)

Going all the way to the Super Bowl can sometimes work against a coach, as it may have with Lewis, or McDaniels or Patricia in the past. Returning to the same team is the norm, but if you are still on the same team two years later, you may not be head coaching material. None of these six left to become head coaches in the NFL:

Kevin Gilbride (2011 NYG OC)

Gregg Williams (2009 NOR DC)

Ron Meeks (2006 IND DC)

Greg Robinson (1998 DEN DC)

Fritz Shurmur (1996 GNB DC)

Ernie Zampese (1995 DAL OC)

- Gilbride was retired/fired after the Giants offense declined after the Super Bowl run.

- Williams had his contract “expire” after the Saints defense collapsed, amid other issues; he resurfaced as the Rams DC for about a month before being suspended for his role in BountyGate (i.e., the other issues).

- Meeks “resigned” — noticing a trend here? — with the Colts after the ’08 season, but was hired as the Panthers defensive coordinator one week later.

- Robinson was fired after the Broncos defense bottomed out in 2000. He went to the Chiefs in 2001, who would not become known for their defense.

- Shurmur, who had a reputation as a defensive genius, left the Packers after the ’98 season to join Mike Holmgren in Seattle. Tragically, Shurmur never coached a game with the Seahawks, passing away of liver cancer that August.

- Zampese was fired along with Barry Switzer after the 1997 season to make room for offensive-minded head coach Chan Gailey.

Three More Years (8)

Matt Patricia (2014 NWE DC)

Perry Fewell (2011 NYG DC)

Bruce Arians (2008 PIT OC)

Tom Moore (2006 IND OC)

Charlie Weis (2001 NWE OC)

Romeo Crennel (2001 NWE DC)

Greg Robinson (1997 DEN DC)

Sherman Lewis (1996 GNB OC)

Patricia, Crennel, and Weis stayed with the Patriots after winning the Super Bowl, winning another Super Bowl two years later, and making a third Super Bowl the next season, before ultimately all leaving for head coaching jobs. The other five?

- Fewell lasted just one more year than Gilbride, as the Giants defense continued to disappoint year after year under Fewell.

- Arians was retired/fired by the Steelers after 2011, and that’s when his career took off. He joined the Colts as offensive coordinator but became head coach after Chuck Pagano stepped aside to battle a cancer diagnosis. Arians would go on to win two AP Coach of the Year awards, in both 2012 and 2014.

- Moore slowly transitioned from OC to senior offensive consultant with the Colts. After the 2009 season, the 71-year-old Moore gave up those duties to Clyde Christensen, and Moore left the Colts after 2010 (he worked with the Jets in 2011, the Titans in 2012, and the Cardinals from 2014 to 2017, so he wasn’t question ready to retire).

- Robinson, as mentioned above was fired three years after the ’97 Broncos won the title (and two years after the ’98 Broncos).

- After Holmgren left the Packers in ’98, Ray Rhodes was brought in to replace him. Lewis, the offensive coordinator, stuck around under the defensive-minded Rhodes, but both were gone when Green Bay brought in Mike Sherman (who was Holmgren’s OC in Seattle in ’99) as head coach in 2000. Lewis went on to the Vikings, but lasted just two years in Minnesota.

Four More Years (3)

Darrell Bevell (2013 SEA OC)

Matt Cavanaugh (2000 BAL OC)

Dave Campo (1995 DAL DC)

Bevell made it back to another Super Bowl with the Seahawks in 2014, but a questionable playcall at the end of that game — do you remember it? — has haunted his tenure ever since. He was finally relieved of his offensive coordinator duties at the end of the 2017 season, and remains a free agent.

Cavanaugh was the offensive coordinator for one of the worst offenses to ever win a Super Bowl. Baltimore’s offense didn’t do any better from ’01 to ’04, and eventually, Cavanaugh was fired by the Ravens. After the season, he got a job as offensive coordinator from the Pittsburgh Panthers under Wannstedt, giving the ’05 to ’08 Pitt Panthers two men who won Super Bowl rings as coordinators. In their first year, Wannstedt and Cavanaugh announced that sophomore Tyler Palko had won the starting quarterback job, causing the backup quarterback to transfer. The Ravens couldn’t have picked a better time to fire Cavanugh, as that backup quarterback was Joe Flacco.

Campo is the big outlier here. He won the Super Bowl as the Cowboys defensive coordinator in ’95, stayed on post-Switzer under the offensive-minded Gailey, and then was named the Dallas head coach for the ’00 season as a way to try to return to the glory days in Texas. The Cowboys went 5-11 in each of his three seasons as head coach.

Five More Years (1)

Dean Pees (2012 BAL DC)

Pees lasted for five more seasons with the Ravens, but was retired/fired. He came out of a month long retirement a couple of weeks ago to become the 2018 Titans defensive coordinator.

Six More Years (4)

Dick LeBeau (2008 PIT DC)

Kevin Gilbride (2007 NYG OC)

Bill Muir (2002 TAM OC)

Monte Kiffin (2002 TAM DC)

LeBeau lasted forever in Pittsburgh, but after winning his second Super Bowl with the Steelers in 2008, the defense gradually began to decline. By 2014, Pittsburgh ranked 18th in both points and yards allowed, and LeBeau resigned after the season (and joined the Titans one month later).

Gilbride got a reprieve by winning another Super Bowl with the Giants in 2011, but as noted above, the offensive decline by 2013 eventually did him in.

Muir and Kiffin lasted as long as Jon Gruden did in Tampa Bay, lasting through the collapse at the end of the 2008 season. But if their post-Gruden career was the same, their pre-Gruden career couldn’t have been any different. Kiffin was the famed defensive coordinator who was 62 when Gruden arrived: he was extraordinarily well-respected but never given a serious look at a head coaching job because of his age (he would later join the Cowboys as defensive coordinator at 73 years old in 2013). Muir? Well, he had an even more unusual history.

Seven More Years (2)

Dom Capers (2010 GNB DC)

Gary Kubiak (1998 DEN OC)

Capers and the Packers won the Super Bowl in 2010 with a defense that ranked in the top 5 in both points allowed and yards allowed. The Packers never again ranked in the top 10 under Capers, and after the pass defense ranked in the bottom five in NY/A in both 2016 and 2017, Capers was finally fired on New Years day, 2018.

Kubiak left to become a head coach, which only happened after the Broncos finally won a playoff game again in 2005. Under Kubiak, Denver won the Super Bowl in ’97 and ’98, ranking in the top 3 in both points and yards both years. The Broncos did that in 2000, too, but Kubiak wasn’t able to land a head coaching job. In fact, after the ’00 season, he interviewed with the expansion Houston Texans, but didn’t get the offer. The Broncos offense regresesd in ’01, but he had four more strong years under Shanahan from ’02 to ’05. But after not winning a postseason game from ’99 to ’04, Denver and Kubiak rebounded in ’05, going 13-3 and earning the 2 seed in the AFC. After the season, he interviewed for the Texans job — and this time, he got it.

Eight (2)

Gary Kubiak (1997 DEN OC)

Pete Carmichael (2009 NOR OC)

Kubiak, of course, is on here because he won titles in both ’97 and ’98.

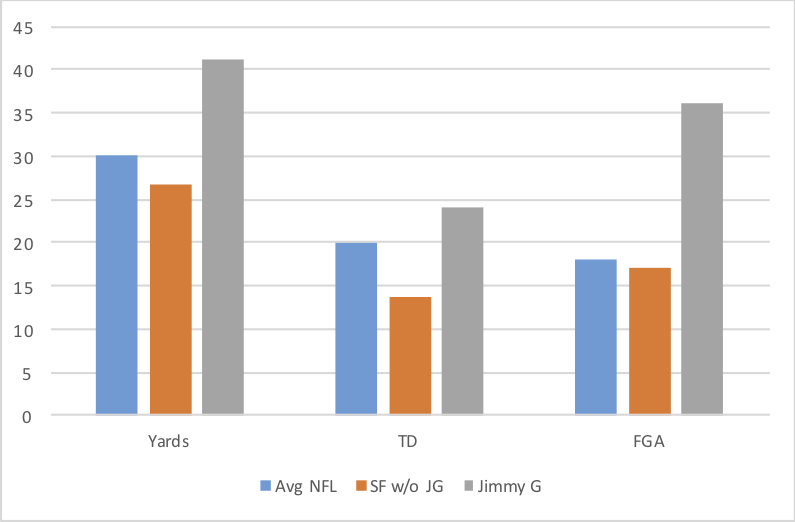

Carmichael? Well, he’s soon about to join the next list: all indications are that he will be back in 2018, which would make for 9 straight years as the Saints offensive coordinator after winning the Super Bowl. Perhaps, like Kubiak, working for a head coach with a reputation as an offensive guru has hurt Carmichael, along with the whole Hall of Fame quarterback thing, too. One could argue that Weis and Bill O’Brien with Brady, Joe Philbin with Rodgers, and Adam Gase with Manning haven’t helped his cause in that regard, as none have had magic touches at quarterback after getting jobs with new teams. But Carmichael is about to enter his 10th season with the Saints, and in his first nine, the Saints rank 1st in yards, 1st in yards per play, and 2nd in points. He’s always been talked about, but never given a serious look, perhaps because he’s viewed as the #3 man on the Saints offense.

It’s unprecedented for a coordinator to win a Super Bowl, and oversee a unit that’s this good for this long without getting a head coaching job.

Nine (1)

Dick LeBeau (2005 PIT DC)

And finally we have LeBeau ’05, who will soon be joined my Carmichael ’09. The difference here is that LeBeau already a job as a head coach with the Bengals and was in his seventies starting in 2007; Carmichael is just 46 years old.