It’s the game’s first play from scrimmage. Your team has the ball, on 1st-and-10, at its own 30-yard line. The quarterback hands it to the running back, who begins running forward.

He avoids a tackle in the backfield, preventing a 1-yard loss. He then runs from the 29 to the 30 to the 31 to the 32…. and so on, until getting tackled at the 45 yard line. He gets high-fives from his teammates as he jogs back to the huddle.

Now, let’s look at you the coach. Which one-yard incremental gain out of those 15 yards made you the happiest? The least-happy? Let’s assume that you are all-knowing, and therefore know the value of each yard gained at all points during a game. If we had a happiness monitor on you, where would it spike? Did the 1-yard gain from the 29 to the 30 make you happy (ignoring for these purposes, the fact that you couldn’t gain the other yards if you didn’t gain the first ones)? Was it the 1-yard gain from the 33 to the 34, putting you in 2nd-and-6? The 1-yard gain from the 39 to the 40, guaranteeing a new set of downs? The 1-yard gain from the 44 to the 45, bringing you ever closer to the end zone?

What about the least happy: that is, which 1-yard gain did almost nothing for you? As it turns out, there’s an answer to that question. And it may surprise you.

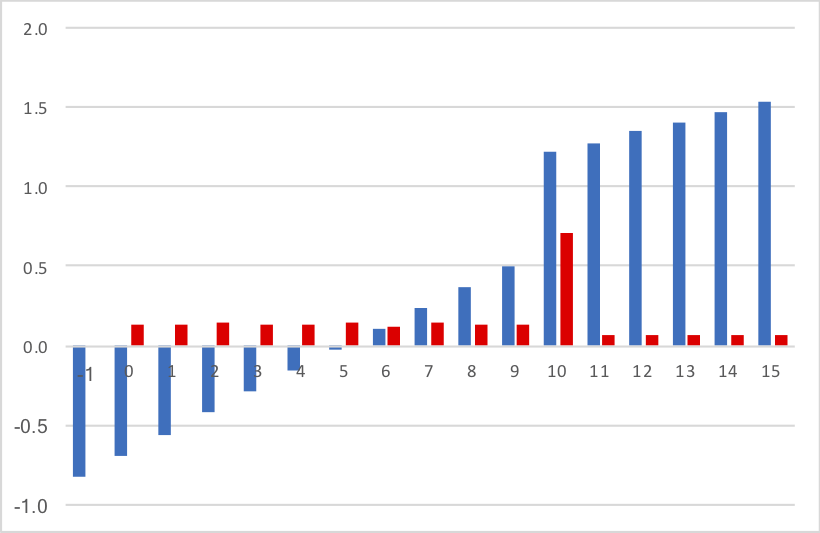

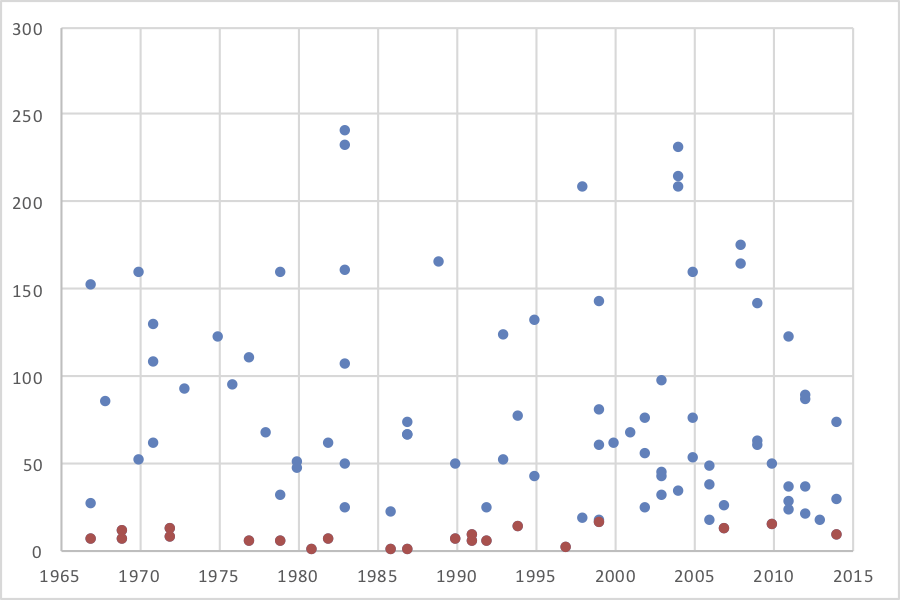

Using the Expected Points Added feature in PFR’s play-by-play log, we can measure how many expected points were added as each yard was gained. That is shown that in blue columns in the graph below. For example, a 1-yard gain is worth -0.4 expected points, because gaining just one yard on 1st down is a bad thing; it sets a team back. Gaining exactly 4 yards is worth 0.0 expected points: it doesn’t change how you think this drive will end. Gaining 12 years is worth nearly 0.8 additional expected points, and gaining 15 yards is worth nearly one full point of EPA. That’s what the blue columns show.

The red columns? They show the marginal expected points added of each additional yard gained. There are three takeaways from looking at the marginal value of each yard: (1) each yard is worth about +0.14 EP up until yard 10; (2) the 10th yard provides zero (or even negative!) value, and (3) all yards after 10 are about half as valuable as the yards gained before 10 yards (about +0.07 EP). Take a look:

This is a bit counter-intuitive. Don’t feel bad if you thought that the 10th yard was the most valuable yard, since that is the yard that moves the chains. But history shows us that it’s better for an offense to have 2nd-and-1 at the 39 than 1st-and-10 at the 40, since 2nd-and-1 is such an advantageous situation for the offense.

Pretty interesting, I think.

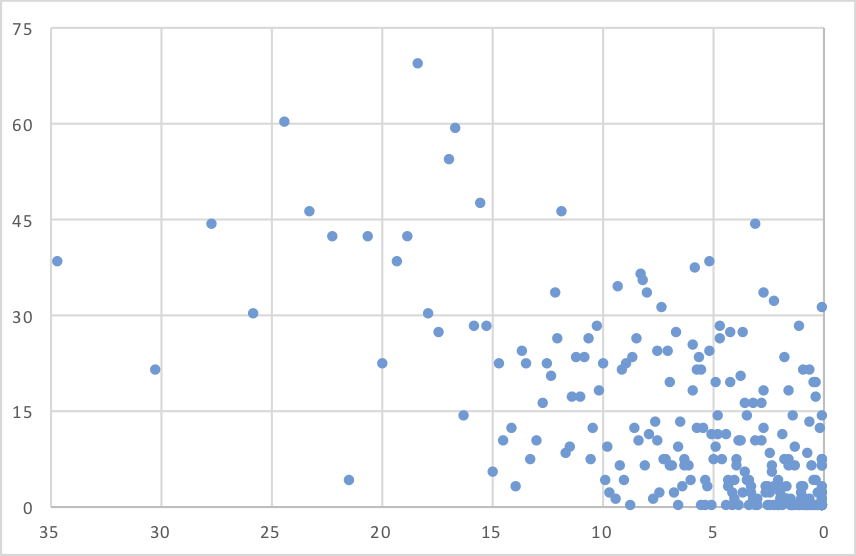

Now, let’s do the same exact exercise but for 2nd-and-10. Once again, each additional yard is worth about 0.14 EP in the beginning, but then we have an enormous jump when it comes to that 10th yard. Gaining 9 yards on 2nd-and-10 is worth 0.50 EPA, but gaining 10 yards is worth 1.21 EPA! That means there are 0.71 EPA assigned to that 10th yard, making it by far the most valuable. And then, once again, the value of each yard gained after picking up a first down drops in half to about 0.07 EPA. The total EPA from each gain is shown in blue, while the red column shows the marginal value of each yard gained.