Last year, Neil wrote a very interesting post on quarterback aging curves. In it, Neil computed the year-to-year differences in Relative ANY/A at every age. While reviewing that post, a lightbulb went off. We can greatly increase the sample size if we only look at running backs from year-to-year, and not just the best running backs on the career level.

There are 723 running backs since 1970 who had at least 150 carries in consecutive seasons and who were between 21 and 32 in the first of those two seasons. For each running back pair of seasons, I calculated how many rushing yards the player gained in Year N and many yards he gained in Year N+1. Take a look:

Just so we’re clear on what that table says, let me walk through an example. There were 43 running backs who were 22-years-old and had at least 150 carries, and also had at least 150 carries at age 23. [1]Careful readers will quickly recognize that this opens us up survivorship bias issues. Running backs who decline greatly from Year N to Year N+1 won’t have their failures recognized in this … Continue reading Those running backs averaged 1,057 yards at age 22 and then 986 yards at age 23. While these numbers may be useful for reference purposes, if you’re like me, a table like this isn’t particularly intuitive; a graph would be much better at explaining what the data tell us.

If we assume that a running back will rush for 1,000 yards at age 21, and then gain or lose the amount of yards showed in the table above each season (i.e., will rush for 89 more yards at age 22, then 70 fewer yards at age 23, then 74 more yards at age 24, and so on), he would produce the following career curve:

The dotted blue line tracks our fictional player who rushed for 1,000 yards at age 21. But the smoothed black line is probably the more useful one, which is presumably a better representation of the effects of age on a running back’s production. What’s interesting to me is that despite using several different variables and measuresh, this study comes to a pretty similar conclusion to the last one: running backs peak at age 26, and then begin a steady decline. It also suggests that for older running backs, some dropoff should always be expected from year-to-year, even if they have done very well in the prior season.

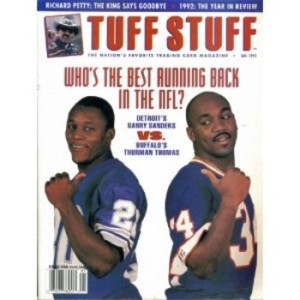

Do you know which running back’s career most closely resembles our set of averages? The answer: Buffalo Bills Hall of Famer Thurman Thomas. The graph below shows Thomas’s yearly rushing averages from ages 22 (when he entered the league) through 33: as you can see, the curve is shifted upwards because he was better than the average back, but the shape of the curves are pretty similar. If nothing else, may you remember that Thurman Thomas aged like your typical running back.

Thomas had a great five-year peak from ages 23-to-27 on which his Hall of Fame career was built. That was followed by a respectable but inferior three-year period; after that, his production fell off a cliff sharply, beginning after his age 30 season.

What can we take from today’s post? The survivorship issue [2]You guys always read the footnotes, right? has not been resolved, although I don’t think it’s a huge issue here. If anything, my guess would be that it understates the degree of magnitude by which older running backs decline. Another conclusion is that running backs don’t take very long to progress in their careers: a running back in the draft is not far behind, if at all, from a running back who is 25 or 26. [3]Of course, we’re focused just on production in the running game here, not things like pass protection. This is your 1,283rd reminder that giving big money contracts to older running backs is one of the riskiest moves an organization can make. Three years ago, a 26-year-old Maurice Jones-Drew led the league in rushing. Over a week into free agency, the 29-year-old running back is still looking for a job. Last season, a 26-year-old Knowshon Moreno gained 1,586 yards from scrimmage and scored 13 touchdowns. He’s still looking for a job, too.

Update: For those curious about the choppiness at the beginning of the curve, the table below shows the results for the 22-year-old running backs:

References

| ↑1 | Careful readers will quickly recognize that this opens us up survivorship bias issues. Running backs who decline greatly from Year N to Year N+1 won’t have their failures recognized in this study if they fail to hit the 150-carry threshold. Unfortunately, I can’t quite think of a good solution right now, but perhaps one will come to me (via the comments?) by the time Part III is produced. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | You guys always read the footnotes, right? |

| ↑3 | Of course, we’re focused just on production in the running game here, not things like pass protection. |