It was just under 5 years ago that the Rams made a blockbuster trade to acquire the number one overall pick to select Jared Goff. As a reminder, in April 2016, the Rams traded:

the 15th overall selection (WR Corey Coleman), the 43rd pick (Austin Johnson), the 45th selection (Derrick Henry), and a third round pick (#76, Shon Coleman), plus next year’s first round pick (which turned into the 5th overall pick and Corey Davis) and third round picks (#100, Jonnu Smith)

to Tennessee for

the first overall pick (Goff), and two later round picks in the 2016 Draft (#113-Nick Kwiatkoski, #177-Temarrick Hemingway)

At the time, the Rams probably didn’t think they would be sending the 5th overall pick in 2017, but that’s one of the risks of trading away a future first round pick. And how did it work out for Los Angeles? It’s tough to say. Goff certainly didn’t live up to expectations: the Rams are explicitly telling the world that Goff is not good enough by trading him and a lot of draft capital to Detroit for Matthew Stafford. On the other hand, not only did Goff have a lot of success with the Rams, but there is some irony in what wound up happening. The concern in sending a lot of draft capital to move up to draft a quarterback is that you wind up in Jetsland, where New York sent a ton of capital for Sam Darnold and then never could build a team around him. The Rams didn’t get the franchise quarterback they wanted, but wound up building a great team around Goff despite the lack of draft capital. One could argue that Los Angeles is one of the top-5 talented teams in the NFL, if you remove the quarterback from the equation.

And that is the gamble Los Angeles is making this weekend. The Rams just sent Goff, along with the team’s first round picks in both 2022 and 2023 and the 88th pick in the 2021 Draft to Detroit for Matthew Stafford. And it’s very interesting what the trade says about not just how the Rams, but the entire NFL, view Goff.

Valuing future picks is always challenging because we have to include the time value discount associated with those picks plus the uncertainty of knowing exactly where they will fall in the draft. This trade is particularly difficult to analyze because it’s initially unclear whether Goff is an asset (a talented, former number one overall quarterback in his prime) or a liability (a quarterback viewed as significantly overpaid with a contract that is going to cost Detroit $54M in cap dollars over the next two years, unless they cut him, in which case he would cost $44M over the next two years).

What do the Lions want to do? If they are looking to tear down the roster and rebuild, Goff may not have a lot of value — and they could look to trade him or cut him in the next 12 months. That would mean he is viewed as a liability, and the Rams actually paid less than they would have for Stafford if they didn’t make Detroit take Goff. On the other hand, are we to assume that no team would have traded for Goff with his existing contract? If even one team (the Colts? Steelers?) would have offered the Rams something, then there would have been no reason to bundle him in this deal. But perhaps his contract really was an albatross: we will only find out once we see what the Lions do with him. As it turns out, we can get a pretty good sense of whether Goff is an asset or a liability by analyzing the rest of the trade. More on that in a moment.

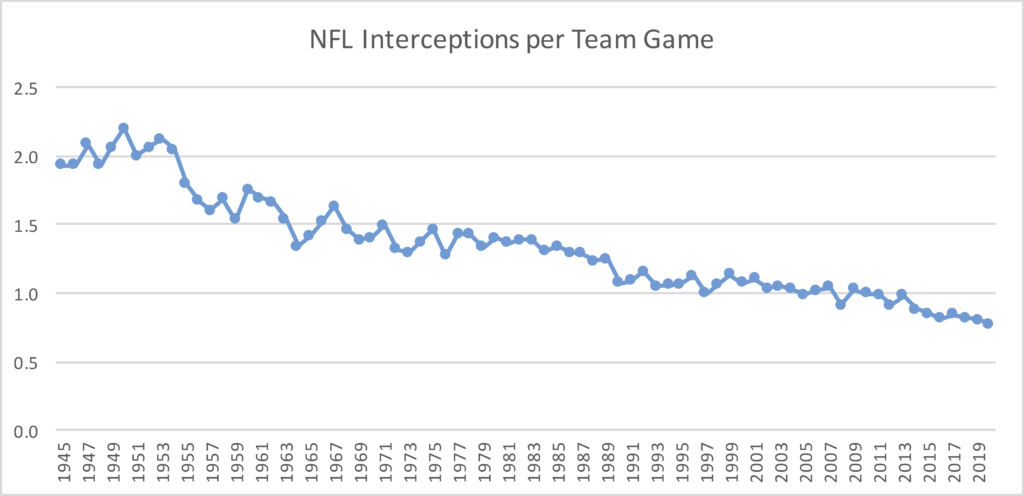

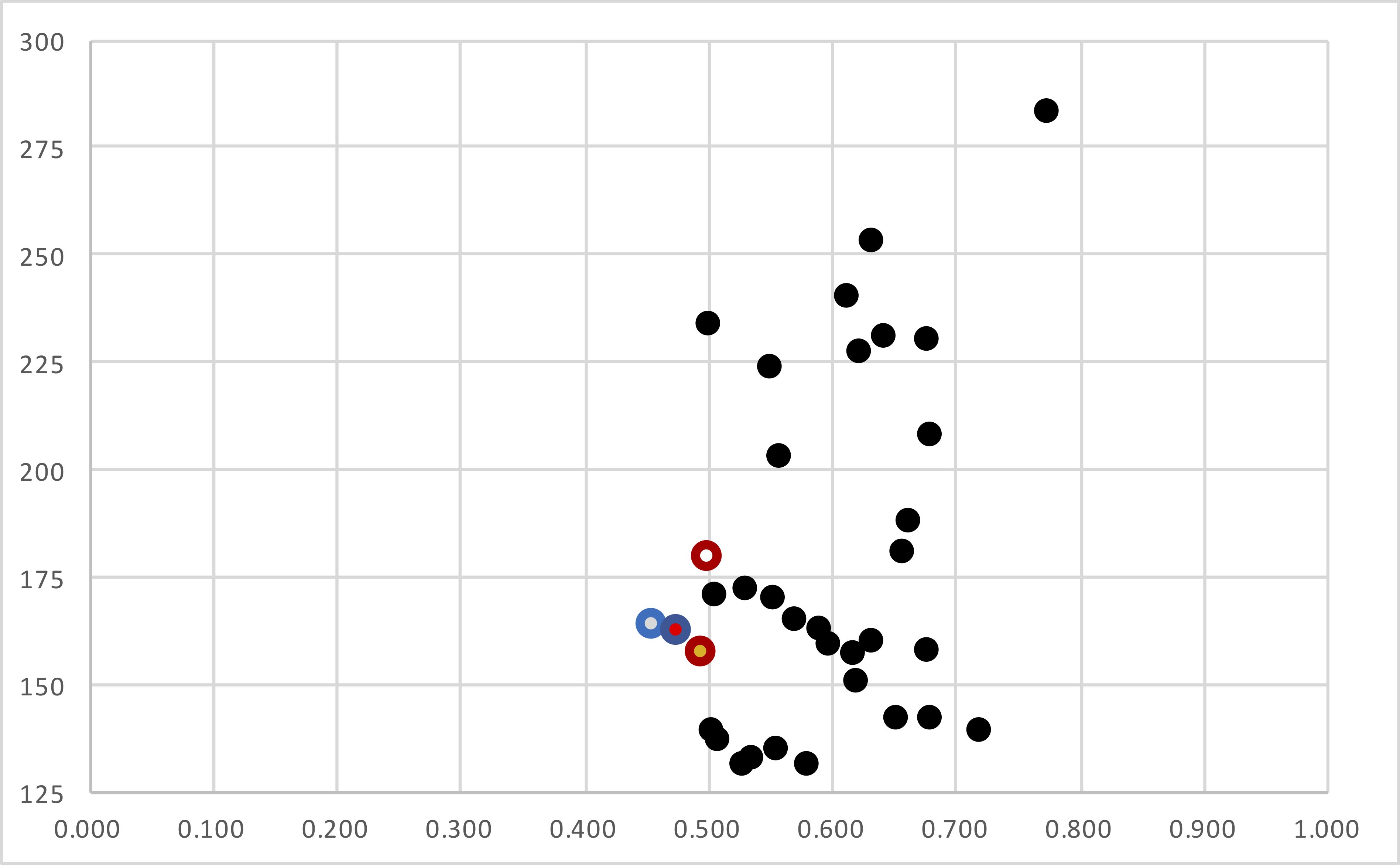

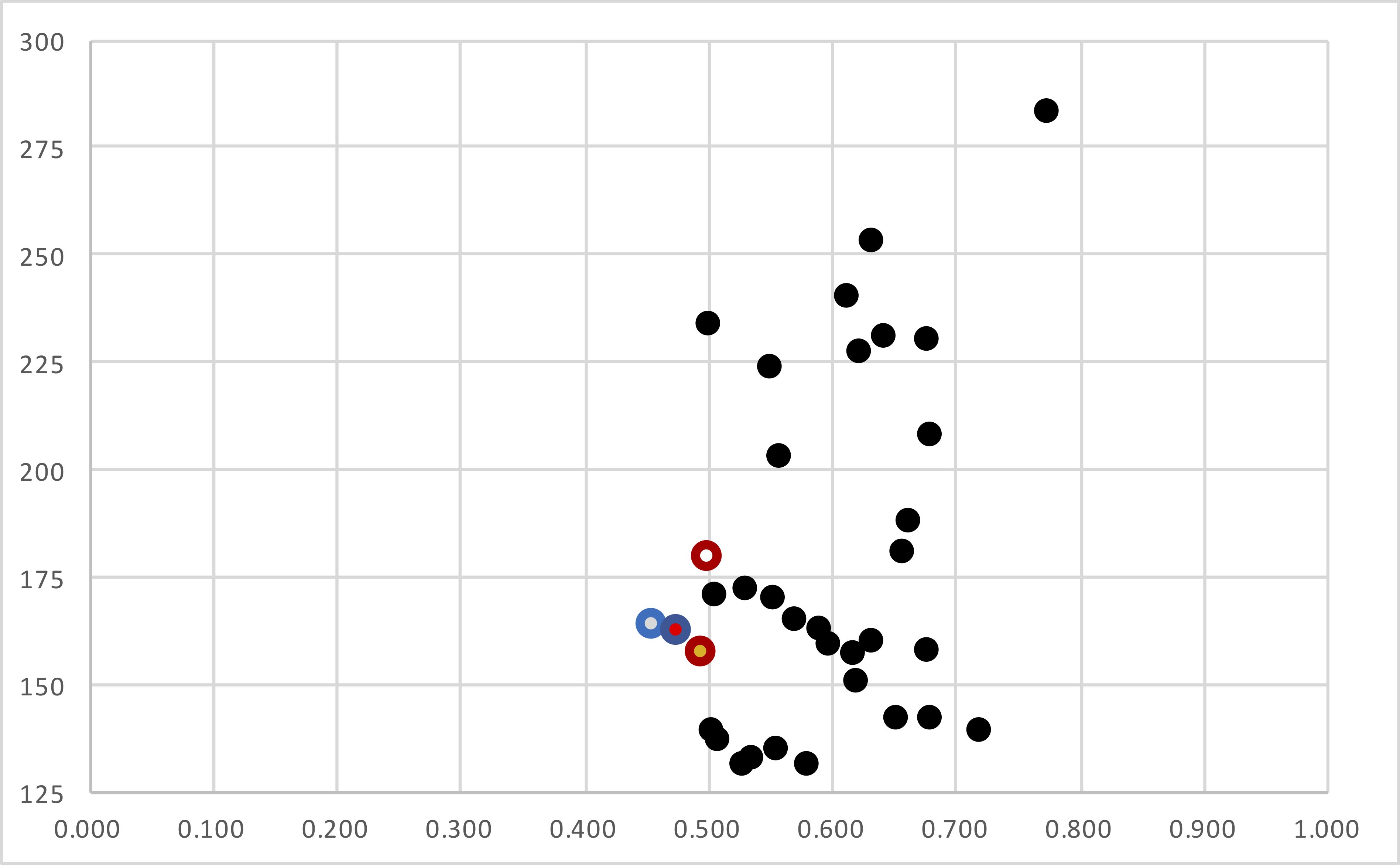

For Detroit, this closes the book on the Stafford chapter. Did he disappoint in Detroit? I think the better summary is that he was a very good player saddled on a bad franchise. There are only four quarterbacks to start 130+ games with one team despite having a losing record: Stafford, Joe Ferguson, Jim Hart, and John Brodie. Here is every quarterback-team relationship with 130+ starts, with their collective winning percentage on the X-Axis and their number of starts on the Y-Axis. I have put Stafford, Ferguson Hart, and Brodie in team colors; yes, Stafford has the worst winning percentage of the group.

So how much is Los Angeles giving up to get Stafford? Some NFL teams put a full round discount on future picks, which would make a 2022 1st round pick equal to a 2021 2nd round pick, and a 2023 1st round pick equal to a 2021 3rd round pick. That is more justifiable when, like with the Rams, the expectation at least is that those first round picks will not be top-10 picks. If we use the Jimmy Johnson calculator, and treat the ’22 1st as equivalent to the 45th pick and the ’23rd 1st like the 75th pick, that implies L.A. sent value equal to the 20th or 21st pick in this year’s draft. But that is probably the wrong way to analyze the situation: it assumes too significant a discount, as we would expect Stafford to be worth more than that (for example, Indianapolis has a quarterback need and the 21st overall pick in this year’s draft, and that presumably would not have been enough to get Stafford).

So if that discount is too high, how do we determine the right discount? Let’s start by saying the average first round pick is worth 18.4 points on my chart, equivalent to the 13th overall selection (because the dropoff in value is logarithmic). On the JJ Chart, the average first round pick is about the same, falling in between the 12th and 13th overall picks.

If we use a 10% discount rate, that would make a 2022 1st round pick equal to the 17th pick on my chart and the 15th on the JJ Chart. Use a 20% discount rate, and a 2022 1st round pick is equal to the 23rd pick on my chart and the 17th on the JJ chart; a larger discount rate than that is hard to justify. For a 2023 1st round pick, using a 10% discount rate, we get the 22nd pick or the 17th pick on the FP and JJ charts, and equivalent to the 36th pick and the 24th pick in 2021 using a 20% discount rate.

Here, the Rams are getting Stafford, a relatively known commodity. Does that argue for a higher discount rate? Perhaps so. So let’s say we use the 20% number. How do we value the 88th pick in this year’s draft plus the two first rounders the next two years? If we consider the 2022 and 2023 first round picks to be average in value, and then apply a 20% discount, those picks combined with the 88th overall selection are equivalent to the 32.6 points on the Football Perspective Draft Value Chart and 1817 points on the traditional, JJ Chart. That’s equal to between the 1st and 2nd picks on my chart, or the 4th pick on the traditional chart.

And that is… a lot. I feel pretty confident in saying that such a collection of picks is worth more than Stafford alone. The Jets and Dolphins are the 2nd and 3rd picks, and I don’t see any reason to think either team would trade that pick for Stafford. Miami in particular might be a great landing spot for a player like Stafford, but there was no indication that the Dolphins were willing to offer up the 3rd overall pick for Stafford.

Which means the Rams — and the NFL — must view Goff as a liability. Stafford alone isn’t worth the 3rd pick in the draft, but Stafford is worth the 3rd pick along with Goff’s contract.