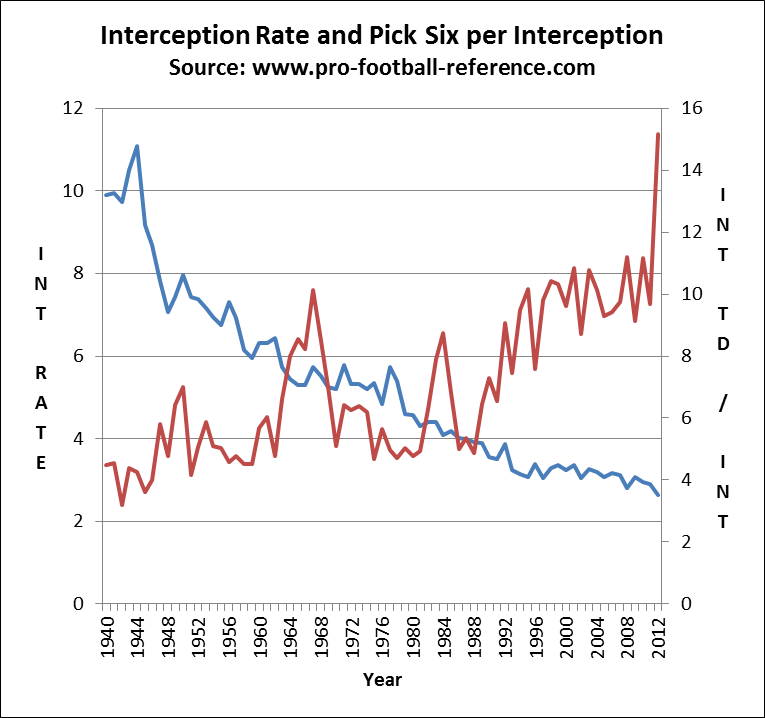

Last week, I wrote about why I was not concerned with Trent Richardson’s yards per carry average last season. I like using rushing yards because rush attempts themselves are indicators of quality, although it’s not like I think yards per carry is useless — just overrated. One problem with YPC is that it’s not very stable from year to year. In an article on regression to the mean, I highlighted how yards per carry was particularly vulnerable to this concept. Here’s that chart again — the blue line represents yards per carry in Year N, and the red line shows YPC in Year N+1. As you can see, there’s a significant pull towards the mean for all YPC averages.

I decided to take another stab at examining YPC averages today. I looked at all running backs since 1970 who recorded at least 50 carries for the same team in consecutive years. Using yards per carry in Year N as my input, I ran a regression to determine the best-fit estimate of yards per carry in Year N+1. The R^2 was just 0.11, and the best fit equation was:

2.61 + 0.34 * Year_N_YPC

So a player who averages 4.00 yards per carry in Year N should be expected to average 3.96 YPC in Year N+1, while a 5.00 YPC runner is only projected at 4.30 the following year.

What if we increase the minimums to 100 carries in both years? Nothing really changes: the R^2 remains at 0.11, and the best-fit formula becomes:

2.63 + 0.34 * Year_N_YPC

150 carries? The R^2 is 0.13, and the best-fit formula becomes:

2.54 + 0.37 * Year_N_YPC

200 carries? The R^2 stays at 0.13, and the best-fit formula becomes:

2.61 + 0.36 * Year_N_YPC

Even at a minimum of 250 carries in both years, little changes. The R^2 is still stuck on 0.13, and the best-fit formula is:

2.68 + 0.37 * Year_N_YPC

O.J. Simpson typifies some of the issues. It’s easy to think of him as a great running back, but starting in 1972, his YPC went from 4.3 to 6.0 to 4.2 to 5.5 to 5.2 to 4.4. Barry Sanders had a similar stretch from ’93 to ’98, bouncing around from 4.6 to 5.7 to 4.8 to 5.1 to 6.1 and then finally 4.3. Kevan Barlow averaged 5.1 YPC in 2003 and then 3.4 YPC in 2004, while Christian Okoye jumped from 3.3 to 4.6 from 1990 to 1991.

This guy knows about leading the league.

Those are isolated examples, but that’s the point of running the regression. In general, yards per carry is not a very sticky metric. At least, it’s not nearly as sticky as you might think.

That was going to be the full post, but then I wondered how sticky other metrics are. What about our favorite basic measure of passing efficiency, Net Yards per Attempt? For purposes of this post, an Attempt is defined as either a pass attempt or a sack.

I looked at all quarterbacks since 1970 who recorded at least 100 Attempts for the same team in consecutive years. Using NY/A in Year N as my input, I ran a regression to determine the best-fit estimate of NY/A in Year N+1. The R^2 was 0.24, and the best fit equation was:

3.03 + 0.49 * Year_N_NY/A

This means that a quarterback who averages 6.00 Net Yards per Attempt in Year N should be expected to average 5.97 YPC in Year N+1, while a 7.00 NY/A QB is projected at 6.45 in Year N+1.

What if we increase the minimums to 200 attempts in both years? It has a minor effect, bringing the R^2 up to 0.27, and producing the following equation:

2.94 + 0.51 * Year_N_NY/A

300 Attempts? The R^2 becomes 0.28, and the best-fit formula is now:

2.94 + 0.53 * Year_N_NY/A

400 Attempts? An R^2 of 0.26 and a best-fit formula of:

3.18 + 0.50 * Year_N_NY/A

After that, the sample size becomes too small, but the takeaway is pretty clear: for every additional yard a quarterback produces in Year N, he should be expected to produce another half-yard in NY/A the following year.

So does this mean NY/A is sticky and YPC is not? I’m not so sure what to make of the results here. I have some more thoughts, but first, please leave your ideas and takeaways in the comments.