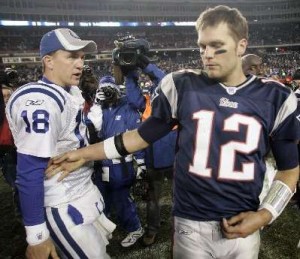

The teacher and the pupil.

has had an incredible career revival since

Jim Harbaugh came to San Francisco. The first six seasons of his career,

Alex Smith won just 38% of his 50 starts, but he has an incredible 15-3 regular season record since 2011 (83%). From 2005 to 2012, Smith had an ugly 72.1 passer rating, the worst of any quarterback with

1500 attempts over that span. Since Harbaugh came to town, Smith has a 93.6 passer rating,

the 7th best mark of any quarterback over that time frame.

But there are two other, related, metrics, that indicate a fundamental shift in Smith’s style of play. In 2011, Alex Smith led the NFL in interception rate, but he also led the league in sacks. Smith threw an interception on just 1.1% of his passes in 2011 but took a sack on 9.0% of his dropbacks; this year, his sack rate has jumped to 10.9% while he has yet to thrown an interception.

Last year, the average quarterback threw an interception on 2.9% of his passes and was sacked on 6.4% of his dropbacks, meaning Smith’s interception rate was just 39% of the league average while his sack rate was 41% higher than league average. Smith also averaged just 197 passing yards per start, 80% of the league average metric.

It’s extremely early, of course, but Smith looks to be on a similar path this year. Which made me wonder: how often does a quarterback have a two-year stretch with (1) an excellent interception rate, (2) a bad sack rate, and (3) a below-average amount of passing yards per game? The answer is very rarely.

There’s a lot of information to present, so I’ve overloaded the table below. This lists all quarterbacks since 1978 who over a two-year period had a sack rate at least 30% higher than average, an interception rate of 70% of league average or lower, and were below league average in passing yards per game. After the traditional categories, I’ve listed each quarterback’s sack rate, interception rate and yards per game, and then how their sack rates, interception rates and yards per game compared to league average. The last two columns show the quarterback’s record over those two years.

During Jim Harbaugh’s 4 years in Indianapolis, he was essentially Alex Smith. He had a 9.6% sack rate and a 2.1% interception rate, while averaging under 180 passing yards per game. When discussing Joe Namath, I noted that he almost never took sacks, which by some measures penalized him because it drove down his completion percentage and increased his interception rate. You can put Alex Smith and the Indianapolis version of Jim Harbaugh on one end of a spectrum and Joe Namath on the other. Both interceptions and sacks are bad, but to some extent, quarterbacks can decide whether they want to throw interceptions or take sacks. Smith, under Harbaugh’s tutelage, has clearly chosen the latter.

On a team with a great defense, that can work. Namath’s defenses weren’t always good, but when they were, the Jets were Super Bowl contenders. When the defenses struggled, Namath pressed even more, and ended up throwing even more interceptions. Smith is never asked to do too much, and Harbaugh has surrounded him with enough talent on the other side of the ball to make that a winning formula.

From 1994 to 1996, Jim Harbaugh went just 20-26 with the Colts. In 1997, Harbaugh had the lowest interception rate in the NFL and the second highest sack rate in the league. But the 1997 Colts ranked in the bottom 5 of the NFL in points allowed, passing touchdowns allowed, interceptions forced, rushing yards allowed, rushing touchdowns allowed and yards per carry allowed. The team went 3-13 overall, and 2-9 with Harbaugh, indicating that this conservative philosophy has its limitations.

Often times we use stats as a way to rank players, where more of one stat or less of another means a player is good, and less of one stat and more of another means a player is bad. But stats can also be used descriptively without overarching themes of good or bad. Just like some running backs are big and slow and others are small and fast, some quarterbacks are risky and some are risk-averse.

Harbaugh clearly was a risk-averse player in Indianapolis under Lindy Infante. What about the other players on the list? Conservative and risk-averse were good adjectives to describe Charlie Batch’s first two years in the league. In 1998, he had Barry Sanders, but Batch’s numbers were nearly identical both seasons (of course, you would normally expect some improvement by a quarterback betwen year one and two). It looks like he played things very safe as a rookie on a good team in 1998, and let’s not forget how he got the starting job: Scott Mitchell was benched after throwing a pick-six in overtime. We can safely conclude that Batch was told to avoid interceptions at all costs, for many reasons.

Steve Young led the league in passer rating in ’96 and ’97, and for many reasons, doesn’t really feel like a comparable player to Alex Smith. He had already been a two-time MVP by 1996.

Ken O’Brien was a very accurate quarterback who led the league in interception rate in ’85, ’87 and ’88. But he took a ton of sacks, in part because of a below-average offensive line. At his peak he was better than Smith has been so far — in ’85 he was 2nd in yards per attempt and he was 5th in that metric in ’86 — but there are some similarities between the two players.

From 1982 to 1986, Neil Lomax had a 10.5% sack rate but a tiny 2.8% interception rate; despite the conservative nature, his team went just 30-36-2 over that span. Lomax was outstanding in 1984, but otherwise was a solid but unspectacular player during this span (Lomax made the Pro Bowl in ’87 when he led the league in completions, attempts, and passing yards.) Lomax also benefited from consecutive All-Pro seasons from Roy Green in ’83 and ’84, but poor defenses prevented Lomax from compiling a winning record in St. Louis.

In the early ’80s, Steve Bartkowski had some success under Leeman Bennett, and made the Pro Bowl in ’80 and ’81. During those years, he was at or above average in sack rate and also interception rate, but then his interception rate improved dramatically in ’83 while his sack rate fell off for the rest of his career. A likely explanation is the hiring of Dan Henning that season, who may have emphasized a more conservative approach.

The two years before Harbaugh arrived, Smith had a 6.2% sack rate and a 3.1% interception rate, both numbers which were pretty close to league average. But Alex Smith 2.0 is not trying to prove to the world that he’s the #1 pick who can do everything; this version is concerned with minimizing risks at all costs. So far, it’s been a very successful formula.