The table below shows the leader in rush attempts for every three year period beginning with the AFL-NFL merger. Here’s how to lead the Lynch line: From 2011 to 2013, Lynch, who was 27 in 2013, led the NFL in carries. Over that period, he rushed 901 times for 4,051 yards, a 4.50 yards per carry average. [continue reading…]

Jerome Bettis is a polarizing Hall of Fame candidate. I’m on the fence with the Bus; I don’t think he’s as deserving as Steelers fans think, but he’s a more deserving candidate than those who mostly remember end-of-career-Bus remember. One thing I’ve heard from time to time about Bus is that he was the greatest “big” back of all time. That’s undoubtedly true, assuming you set the weight [1]Try the veal. high enough. Bettis had an official playing weight of 252 pounds, and no running near that weight can match his resume. Cookie Gilchrist, Pete Johnson, Marion Butts, Christian Okoye, Natrone Means, and Mike Alstott had short bursts of success, but they can’t match Bettis’ longevity. Players like Jamal Lewis, Michael Turner, Larry Csonka, Eddie George, Jim Brown, Franco Harris, John Riggins, and Earl Campbell carried the “big back” label, but all were 10-25 pounds lighter than the Bus.

I looked at every running back in history, and calculated his number of rushing yards over 500 in each season (to avoid giving undue weight to compilers). After adjusting for season length, I then calculated career grades in this statistic. In the graph below, the Y-Axis shows this career rushing grade, while the X-axis displays weights. Bettis is represented on the far right with the code “BettJe00.”

References

| ↑1 | Try the veal. |

|---|

Regular readers know that I’m skeptical of using “yards per carry” to evaluate running backs. That’s because YPC is not very consistent from year to year. But it’s also not consistent even within the same year. For example, In 2013, Giovani Bernard rushed 92 times for 291 yards in even-numbered games last year, producing a weak 3.16 YPC average. But in odd-numbered games, Bernard averaged 5.18 YPC, rushing 78 times for 404 yards!

Jamaal Charles also showed a preference for odd-numbered games, averaging 5.80 YPC in games 1, 3, 5, etc., and only 3.96 YPC in even-numbered games. Buffalo’s C.J. Spiller had a reverse split, producing 5.57 YPC in even games and 3.61 YPC in odd games.

Okay, this stuff is meaningless, you say. Who cares about these random splits? Well, there are a couple of reasons to care. For starters, these splits serve as a great reminder that splits happen. If Spiller averaged 3.61 YPC in the first half of the year and 5.57 in the second half, the narrative would be that Spiller was finally healthy by the end of the year, and was set up for a monster 2014 campaign. Meanwhile, if Charles had seen his YPC fall from 5.8 YPC in the first eight games to 3.96 in the back eight, the narrative would be that he couldn’t handle a heavy workload, was breaking down, and could be a huge bust this year. Narratives are easy to invent, and remembering that “splits happen” is an important part of any analysis. [continue reading…]

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a list of the best rushing teams in 2013 using Adjusted Yards per Carry. That metric, you may recall, is calculated as follows:

Rushing Yards + 20*RushingTDs + 9*RushingFirstDowns

We can use the same formula to grade every team across history. To account for era and quantity (having more above-average rush attempts is better), I calculated each team’s AdjYPC average, subtracted the league-average AdjYPC average, and multiplied that difference by the team’s number of rush attempts.

The top team by this method isn’t even an NFL team: it’s the 1948 San Francisco 49ers. You may recall that the 49ers and Browns staged two epic battles that season, and may have been the best two teams in pro football. That season, San Francisco averaged 6.1 yards per carry and rushed for 35 touchdowns on 600 carries; along with 152 first downs, and the 49ers averaged 9.5 Adjusted yards per Carry. That’s the highest average ever, just narrowly topping the production of the franchise’s Million Dollar Backfield six years later. Joe Perry was on both teams because Joe Perry was the man.

The table below shows the traditional rushing data for the top 200 rushing teams of all time; the VALUE column represents the number of Adjusted Rushing Yards produced above average (i.e., relative to the league average AdjYPC). I’ve also listed the three most prominent rushers on each team. [continue reading…]

Mendenhall ended the season with 687 yards on 217 yards, a 3.2 yards per carry average. Ellington finished his rookie year with 118 carries for 652 yards, producing 5.5 yards per rush. One way to measure the magnitude of the difference in the effectiveness of these two players — and boy was there a large difference — is to simply look at the delta in the players’ yards per carry averages. In this case, that’s 2.36 yards per carry.

Where does that rank historically? Some teams — I’m looking at the Lions in the early Barry Sanders years — gave only a handful of carries to their backup running backs. So one thing we can do is to take the difference in the yards per carry between the team’s top two running backs and multiply that number by the number of carries by the running back with the lower number of carries. In each instance, I’ve defined the running back with the most carries as the team’s RB1, and the running back with the second most carries as the RB2. In Arizona’s case, that would mean multiplying -2.36 (Mendenhall’s average, since he was the RB1, minus Ellington’s average) by 118, the number of carries Ellington recorded. That produces a value of -278. [continue reading…]

Over the last three years, Chris Johnson has rushed 817 times for 3,367 yards, a 4.12 yards per carry average. Over the last three years, the Jets have had running back seasons where a rusher recorded at least 150 carries: Bilal Powell and Chris Ivory in 2013, and Shonn Greene in both 2011 and 2012. Collectively, in those four seasons, the group rushed 887 times for 3,647 yards, a 4.11 yards per carry average.

If you put a lot of stock in yards per carry as a metric, it would seem as though Johnson won’t be bringing much to New York in the running game. But today we’re going to take a closer look at the production of Johnson and the Jets back. And I’ve created some graphs that I think are pretty interesting.

Because Johnson has 817 carries since 2011 and the Jets backs have 887, we can’t just compare things on a carry per carry basis (i.e., 20th best carry for each). So instead, I’m going to look at their percentile ranks — i.e., how many yards they gained on X percent of their carries. This first chart looks at the percentile ranks for Johnson and the Jets backs over the last three years. For example, 22% of Johnson’s runs have gone for negative yards or no gain, while the 22nd percentile of Jets runs has been for one yard. In the table below, the X-axis represents percentile, and the Y-axis represents yards gained. In this chart, being higher is better, and the Jets green line is higher or even with Johnson’s blue line on about 75% of all runs. Then, at the end, things switch, with Johnson being more productive with respect to each group’s best runs. [continue reading…]

Today I want to look at how traditional rushing statistics compare to rushing Expected Points Added, one of the main stats used over at Advanced Football Analytics. In my analysis, I used the EPA numbers for each team in each season from 2002 to 2013.

Stickiness from year to year

Yards per carry is not a sticky metric: by that, I mean, it is not very consistent from year to year. The correlation coefficient between a team’s yards per carry in Year N and yards per carry in Year N+1 was just 0.31. Sometimes the square of the correlation coefficient is described in terms of “explanatory power”: loosely speaking, this means roughly 10% of a team’s YPC average in Year N+1 can be explained by its YPC average in Year N.

Now, a lot of metrics aren’t sticky from year to year, because the NFL is a highly competitive league. In fact, Rushing EPA per play has a lower correlation coefficient from year to year at just 0.30. That’s a strike against EPA. On the other hand, Burke’s success rate metric has a CC of 0.39, which is more impressive. The CC for Net Passing Yards per Attempt year over year is 0.43. [continue reading…]

There is no doubt that in modern times, passing is king. But until pretty recently, we were at the peak level in NFL history with respect to individual rushing performance. On the team level, rushing production ebbed and flows, with high points in the late ’40s, mid-’50s, and mid-’70s, but on the individual level, the 2006 season may have been the high point.

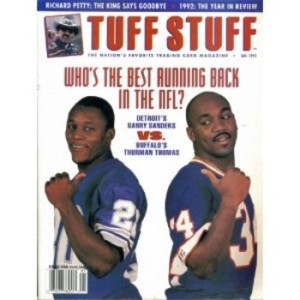

That year, Pittsburgh’s Willie Parker rushed 337 times for 1,494 yards and scored 13 touchdowns, but Parker ranked just sixth in rushing yards. He also caught 31 passes for 222 yards, but Parker ranked only 7th in yards from scrimmage. That season, the average leading rusher on the 32 teams gained 1,124 rushing yards. Again, that was average. Last year, the average leading rusher gained 912 yards. Consider that in 1991, after Emmitt Smith, Barry Sanders, and Thurman Thomas, the fourth-leading rusher was New York’s Rodney Hampton, and he gained 1,059 yards. In other words, 2006 and its surrounding seasons — even if it might not feel like it — really was a different era of football for running back statistics.

The graph below shows the average rushing yards gained by the leading rushing for each team in every season since 1932. All team seasons of fewer than 16 games were pro-rated to 16 games [1]But this does not pro-rate for injury.; the NFL line is in blue, while the AFL/AAFC line is in red. [continue reading…]

References

| ↑1 | But this does not pro-rate for injury. |

|---|

A couple of weeks ago, Brian Burke of Advanced Football Analytics (formerly Advanced NFL Stats) wrote a great post on the value of a first down. From that post, we concluded that the marginal value of a first down is 9 yards, and we’ve previously determined that the marginal value of a touchdown is 20 yards. Therefore, we can create an Adjusted Yards per Carry statistic, which can be calculated as follows:

Adjusted Yards per Carry = (Rushing Yards + 20 * Rushing TDs + 9 * Rushing First Downs) / Rushes

If we use this metric to analyze the 2013 season, how would it look? Last year, the Eagles averaged 5.13 yards per carry and 8.29 Adjusted YPC, courtesy of the fact that the team led the NFL in rushing first downs. Philadelphia also ranked 1st in the NFL in both of those metrics and in overall rushing yards. [continue reading…]

- Calculate the percentage of yards from scrimmage a running back gained in each season as a percentage of his career yards from scrimmage. For example, if a player gained 10% of his yards from scrimmage in 1999 and the team went 15-1 that season, then 10% of the running back’s weighted winning percentage would be 0.9375. This is designed to align a running back’s best seasons with his team’s records in those years. For example, Emmitt Smith played 2 of his 15 seasons with the Cardinals. But since he gained only 6.5% of his career yards from scrimmage in Arizona, the Cardinals’ records those years count for only 6.5% — and not, say, 13.3% — of his career weighted winning percentage.

- Add the weighted winning percentages from each season of the player’s career to get a career weighted winning percentage.

At the time, Steven Jackson had the lowest average adjusted winning percentage of any running back in my study. Since then, Jackson played for the 7-8-1 Rams in 2012 and the 4-12 Falcons in 2013. That upped his adjusted winning percentage from 0.292 to 0.307. Among the 129 running backs in NFL history with at least 7,000 yards from scrimmage, only James Wilder had a worse career adjusted winning percentage.

The running back with the highest adjusted winning percentage is Lawrence McCutcheon, who spent the majority of his career with the Rams before end-of-career cups of coffee with Denver, Seattle, and Buffalo. The table below shows the first and last year for each running back, the teams he played for, his career yards from scrimmage, and his adjusted winning percentage. McCutcheon played on those great Rams teams of the ’70s, gaining the bulk of his yards from ’73 to ’77. As a result, his adjusted winning % is an incredible 0.741: [continue reading…]

At the end of my Seahawks-Saints playoff preview, I came up with (what I thought was) a pretty neat bit of trivia:

New Orleans gained 4918 passing yards and allowed only 3105 passing yards. That 1813 yard difference is largest by any NFL team in history. The 1961 Oilers, led by George Blanda, Bill Groman, and Charley Hennigan, actually gained 2,001 more passing yards than they allowed, but Houston of course was an AFL team. And there’s a bit of an asterisk here because of the games played: the 1943 Bears, 1951 Rams, and 1967 Jets also had a larger passing yards differential on a per-game basis. But regardless, that puts the Saints in some pretty impressive company. The Oilers, Bears, and Rams all won their league’s championships that season, and Joe Namath’s Jets won the Super Bowl the next season. The team with the fifth largest passing yards differential on a per-game basis, prior to the Saints, was the 2006 Colts, also a Super Bowl champion.

I never ran the same numbers but for rushing yards, because I just assumed it would be dominated by the ’72 Dolphins and other similar teams. But as it turns out, the undefeated Dolphins rank only third in net rushing yards in a single season since 1950, even on a per-game basis. In 1972, Miami rushed for an amazing 2,960 yards, but allowed 1,548 yards on the ground to opposing teams. That comes out to a 1,412 yard difference, or a +100.9 rushing yards per game differential.

The 2001 Steelers, with Kordell Stewart, Jerome Bettis, and a suffocating defense, finished with a +98.7 differential, the fifth best differential since 1950. The ’84 Bears, behind Walter Payton and their own dominant defense, checks in at #4 at +99.8. The second best performance is owned by the ’76 Steelers, who finished with a +108.1 differential. That was the year Pittsburgh allowed just 28 points over the team’s final 9 games, and Franco Harris and Rocky Bleier both hit the 1,000-yard mark (they were the second duo to do so, behind Larry Csonka and Mercury Morris on the ’72 Dolphins).

None of those teams caused me any surprise, which I guess is why I never ran the numbers until today. But it would have taken me quite a few more guesses to come up with the number one team on the list. That’s why I’ll give you guys some hints. [continue reading…]

Last year, I provided a starting point for my running back projections. The idea is pretty simple: some fantasy statistics are much more repeatable, or sticky, than others. Over at Footballguys.com, I used the following formula to help isolate those factors:

1) Rushing Yards (R^2 = 0.47). The best-fit formula to predict rushing yards is:

-731 + 3.73 * Rush Attempts + 180 * Yards/Rush

2) Receptions (R^2 = 0.42). The best-fit formula to predict receptions is:

11.1 + 0.39 * Receptions + 0.032 * Receiving Yards

3) Receiving Yards (R^2 = 0.38). The best-fit formula to predict receiving yards is:

83.7 + 1.65 * Receptions + 0.46 * Receiving Yards

4) Rushing Touchdowns (R^2 = 0.29). The best-fit formula to predict rushing touchdowns is:

0.1 + 0.0037 * Rushing Yards + 0.35 * Rushing Touchdowns

5) Receiving Touchdowns (R^2 = 0.23). The best-fit formula to predict receiving touchdowns is:

0.1 + 0.0022 * Receiving Yards + 0.25 * Receiving Touchdowns

Using these formulas, we can come up with a good starting point for your 2014 running back projections.

You can read the full article here.

Only two players in NFL history have ever rushed for 5,000 yards with two teams. Can you name either of them?

Here’s a couple of hints for the only player to rush for 5,300+ yards with two different teams.

| Trivia hint 1 | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint 2 | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

Here’s a couple of hints for the other player:

| Trivia hint 1 | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint 2 | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

One other player was really, really close.

Here’s a couple of hints for that player:

| Trivia hint 1 | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint 2 | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

Except that’s not the case. It appears as though veteran running backs and college running backs are like Coke and Pepsi at a time when a lot of consumers have decided to stop drinking soda. In 2013, for the first time since 1963, no running back was selected in the first round of the draft. The top back off the board was Giovani Bernard at 37, the longest a draft had ever gone without hearing a running back’s name called. That was until this year, when the first 53 picks came and went without a single running back being selected. Bishop Sankey was the first back off the board to Tennessee with the 54th pick, although Jeremy Hill, and Carlos Hyde were drafted with two of the next three picks.

You’ve heard a lot about how running backs are being devalued in the draft. By nature, I’m a bit of a contrarian, but even I can’t spin this graph, which shows the percentage of draft capital spent on running backs in each NFL draft since 1950: [continue reading…]

Peyton Manning’s time in Indianapolis was peppered with record-breaking moments that have been very well-publicized. But a relatively unknown record occurred during the nascent days of the Manning Era. In 1999, Edgerrin James rushed for 1,553 yards, an impressive accomplishment in any era. But here’s what’s really crazy: Manning was second in the team in rushing yards with 73! Keith Elias was the only other running back to record a carry, and he finished with 28 yards (Marvin Harrison and Terrence Wilkins added six total rushing yards). This means James recorded 93.6% of all Indianapolis rushing yards that season, still an NFL record, and one that is in no danger of being broken in the near future.

Second on the list of “largest percentage of the rushing pie” is … Edgerrin James for the Colts the following season. In 2000, he was responsible for 91.9% of all Indianpolis rushing yards. Only three other players have ever gained 90% of all team rushing yards: Emmitt Smith, Barry Sanders, and … Travis Henry. The table below shows the top 100 seasons as far as percentage of team rushing yards: [continue reading…]

In December, I noted that fewer rushing yards are coming from first round picks. That’s a trend that seems very likely to continue in 2014, and perhaps for the foreseeable future. As it turns out, running backs are also getting shorter and heavier.

LeSean McCoy, Alfred Morris, Frank Gore, Knowshon Moreno, Zac Stacy, DeAngelo Williams, Maurice Jones-Drew, Ray Rice, Giovani Bernard, Trent Richardson, Doug Martin, Danny Woodhead, and Mark Ingram are all 5’10 or shorter. As you can probably infer from the sheer quantity of the group, those players aren’t significant outliers: the “average” running back, weighted by rushing yards last season, was only five feet and 11.1 inches tall. That means backs like Jamaal Charles (6’1), Matt Forte (6’1), and Adrian Peterson are more outliers than the 5’10 backs.

This is a weighted average, so McCoy (who had about 3% of all rushing yards from running backs last year) counts three times as much as, say, Donald Brown when calculating the 2013 (weighted) average running back height. Regular readers will recognize that this is the same methodology I used when calculating the average (weighted) average of each team’s receivers last season. The graph below shows the average weighted height of all running backs since 1950: [continue reading…]

The free agent running back market has been as peculiar as it’s been quiet. There have been no big contracts doled out and only a few sizable ones of note, although some of the ensuing narrative about the demise of the running back position has been overblown. Today I want to look at the ten biggest free running back signings [1]Excluding Joique Bell, who was a restricted free agent. of 2014 and see what conclusions we can draw.

Player contracts are notoriously complicated to analyze; I won’t pretend that we can truly and fully measure contracts handed out by ten different teams. But I won’t let the perfect be the enemy of the great: armed with the understanding that this analysis is not perfect, we march onwards. Over The Cap publishes detailed salary cap information, including the total value of the contract, the average per year, the amount of guaranteed money (which is never as clear as it sounds), the guaranteed money per year, the percent guaranteed, and the number of years. I’ve added one additional column: the approximate value of the contract in the first two years, which in itself is pretty tricky to calculate. [2]For players on one-year contracts, I averaged the guaranteed amount and the total amount, and multiplied that average by two. For players on two-year contracts, I averaged the guaranteed amount and … Continue reading It’s not close to perfect, but no method is, and I thought this was a better metric by which to sort the table than any other. Take a look: [continue reading…]

References

| ↑1 | Excluding Joique Bell, who was a restricted free agent. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For players on one-year contracts, I averaged the guaranteed amount and the total amount, and multiplied that average by two. For players on two-year contracts, I averaged the guaranteed amount and total amount. For players on three- or four-year contracts, I treated the first two years as fully guaranteed and ignored the remainder. |

Last year, Neil wrote a very interesting post on quarterback aging curves. In it, Neil computed the year-to-year differences in Relative ANY/A at every age. While reviewing that post, a lightbulb went off. We can greatly increase the sample size if we only look at running backs from year-to-year, and not just the best running backs on the career level.

There are 723 running backs since 1970 who had at least 150 carries in consecutive seasons and who were between 21 and 32 in the first of those two seasons. For each running back pair of seasons, I calculated how many rushing yards the player gained in Year N and many yards he gained in Year N+1. Take a look:

As a disclaimer, I’m in the camp that thinks YPC is an overrated statistic. In 2013, Marshawn Lynch, Eddie Lacy, and Frank Gore all averaged around the league average of 4.17 yards per carry, but that doesn’t make them average backs. So consider much of this post to be a bit of trivia and fun with stats, rather than the best way to identify running back productivity. With that disclaimer out of the way, I calculated each player’s “yards above league average” for each season since 1950, which is the product of a player’s number of carries and the difference between his YPC average and the league average YPC rate.

For example, since Rice averaged 3.08 YPC on 214 carries, he gets credited for being 231 yards below average in 2013. By this measure, Rice was the worst running back in the league. He was worse than his teammate Bernard Pierce (who actually had a lower YPC average but on fewer carries, so he finished 197 yards below average), worse than Willis McGahee (-198) or Rashard Mendenhall (-217), and even worse than Trent Richardson (-220). And this wasn’t your typical worst season in the league, either: his 2013 performance ranks as the 15th worst in this metric since 1950: [continue reading…]

When I went on the Advanced NFL Stats Podcast in late December, I discussed my use of Z-scores to measure the Seattle pass defense. Host Dave Collins asked me if I was planning on using Z-scores to measure other things, like say, Adrian Peterson’s 2012 season. I told him that would be an interesting idea to look at in the off-season.

Well, it’s the off-season. So here’s what I did.

1) For every season since 1932, I recorded the number of rushing yards for the leading rusher for each team in each league. So for the Minnesota Vikings in 2012, this was 2,097.

2) Next, I calculated the average number of rushing yards of the top rusher of each other team in the NFL. In 2012, the leading rusher on the other 31 teams averaged 974 yards.

3) Then, I calculated the standard deviation of the leading rushers for all teams in the NFL. In 2012, that was 386 yards.

4) Finally, I calculated the Z-score. This is simply the difference between the player’s average and the league average (for Peterson, that’s 1,123), divided by the standard deviation. Peterson’s Z-score was 2.91, good enough for 15th best since 1932. The table below shows the top 250 seasons using this method from 1932 to 2013; it’s fully searchable and sortable, and you can change the number of entries shown by using the dropdown box on the left. [continue reading…]

Christian Okoye and Thurman Thomas were second round picks, Barry Word was a third round pick, and the rest of the 700+ yard group (Herschel Walker [1]Who, of course, was morally a first round pick, but fell in the draft because he was in the USFL at the time., Johnny Johnson, Marion Butts, Merril Hoge, Derrick Fenner, and Earnest Byner) was drafted after the fourth round. But the majority of the top running backs were former first round picks.

1990 was a bit of an outlier year. That season, 48.9% of all rushing yards by NFL running backs came from backs selected among the first 30 picks. If you also include the rushing yards produced by Anthony Thompson, Dalton Hilliard, and Ickey Woods — each of whom was drafted 31st overall — the total jumps to 51.1% of all rushing yards by running backs that season. That means the 31st pick in the draft was the tipping point, or median draft slot, for rushing yards by running backs that season.

References

| ↑1 | Who, of course, was morally a first round pick, but fell in the draft because he was in the USFL at the time. |

|---|

How crazy is it for one back in a committee to average more than four more yards per carry than the other back? I ran the following query for every team since 1970:

- First, I noted the two running backs who recorded the most carries for each team

- Next, I eliminated all running back pairs where the lead back had over 150 more carries than the backup.

- I also eliminated all pairings where the lead back was a lead back in name only due to injury to the starter (otherwise, years where Maurice Jones-Drew and Darren McFadden ranked second on their team in carries would be inappropriately included). To do that, I deleted sets where the “lead” back — defined as the back with the most carries — averaged fewer carries per game than the second running back.

After running through those criteria, the table below shows all situations where the backup averaged at least one more yard per rush than the lead back. As always, the table is fully searchable and sortable. It is currently sorted by the difference between the YPC average of the backup and the starter, but you can sort by year to bring the recent instances to the top.

[continue reading…]

As you might expect, much of the blame falls on the Baltimore offensive line. In particular, tackles Michael Oher and Bryant McKinnie have been terrible, so much so that McKinnie was traded to Miami. Pro Football Focus also gives poor run-blocking grades to Ed Dickson, Dallas Clark (unsurprisingly), and Vonta Leach (very surprisingly). I haven’t watched enough of Baltimore to tell you why the Ravens have struggled so significantly to run the ball, but I can provide some perspective on how poorly Rice’s numbers are.

We don’t have play-by-play data going back to 1960, but we do have game-by-game data back that far. I went back and noted every running back who had a season-to-date yards per carry average below 2.80 following the game where he recorded his 97th carry. The table below shows the 43 players to do so from 1960 to 2012, sorted in reverse chronological order. The last player was former Raven Chester Taylor, and here is how his line reads: In 2010, playing for the Bears at age 31, Taylor had 105 carries for 252 yards, producing a 2.4 yards per carry average, following the game where he received his 97th carry of the year. The rest of the season, he had 7 rushes for 15 yards, a 2.14 YPC average.

[continue reading…]

Not too surprising, I suppose. This includes all rushing touchdowns, including in the postseason, but does not include rushing touchdowns for 2013, not that it matters very much for Chris Johnson. :rimshot:

All players with at least 30 rushing touchdowns are included since 1940.

[continue reading…]

- How often does the first running back selected in the draft become the best running back from his class? The field is always a better bet than one player: Only about 40% of the highest-drafted backs led their class in rushing yards as a rookie, with that number dropping to about 33% on a career basis. On the other hand, that’s better than the production of the first-drafted wide receiver.

- In 2012, the field won, as both Doug Martin and Alfred Morris rushed for more yards than Richardson. I then tried to project the number of yards for all three players for 2013 based on their draft status and rookie production; as it turns out, draft status remained extremely important, and Richardson projected to average the most yards per game in year two out of that group (a projection that doesn’t look very good right now).

- In July, I continued to voice my disdain for the use of yards per carry as the main statistic for running backs, when I argued that Richardson’s 3.6 average last year was not important. More specifically, I said if you loved Richardson as a prospect, his 3.6 YPC average in 2012 was not a reason to downgrade him (of course, if you didn’t like Richardson, that’s a different story). Richardson still received a huge percentage of Cleveland carries and had a strong success rate, and I argued that his low YPC was simply a function of a lack of big plays. For a more in-depth breakdown of his rookie season, Brendan Leister compiled a good film-room breakdown of some of Richardson’s mistakes in 2012. Leister noted that Richardson had some mental mistakes, which isn’t atypical of a rookie, and still fawned over the former Alabama star’s physical potential.

- After the trade to Indianapolis, I wrote that Richardson’s ability as a pass blocker was tough to analyze, and advised you to view some of the numbers thrown around in support of Richardson with skepticism. Believe it or not, I still have thoughts on that trade that I just haven’t gotten around to finishing, so look for my hot take on the Richardson deal to be published in say, March.

In 75 carries with the Colts, Richardson is averaging just 3.0 yards per carry. Even though I find yards per carry overrated, there is a certain baseline level of production needed for every running back, and 3.0 falls well short of that number. For his career, Richardson now has 1,283 yards on 373 yards, a 3.44 YPC average. He’ll reach 400 career carries in a couple of weeks, so I thought it might be interesting to look at the YPC averages of all running backs after their first 400 carries.

We can’t measure that exactly through game logs, but what we can do is calculate the career YPC average of each running back after the game in which they hit 400 career carries. The table below shows that number for all running backs who entered the league in 1960 or later and is current through 2012. Let’s start with the top 50 running backs:

[continue reading…]

I’ve written a couple of times about “yards per carry” as a key statistic to grade running backs. The usual argument in favor of using YPC is that a running back who rushes for 1200 yards on 300 carries is less valuable, all else being equal, than one who rushes for 1200 yards on 250 carries. But when it comes to running backs and yards per carry, “all else” is is never equal. Two players come to mind whenever yards per carry is cited for running backs: Eddie George and Curtis Martin.

From 1996 to 2002, George led the league with 2,421 carries. Only Martin (2,236) was within 300 carries of George. In NFL history, Eric Dickerson is the only player to ever record more carries during a player’s first seven seasons. But some would have you believe that George wasn’t very good during those seven years, because he averaged just 3.71 yards per carry. During that stretch, the Titans went 68-44, giving them the fourth best record in the NFL and the second-best mark in the AFC during that span. But, the yards-per-carry proponents would argue, Jeff Fisher didn’t know what he was doing when he kept handing the ball off to George, play after play, game after game, year after year.

In 1998, the Jets went 12-4 and earned a first-round bye; New York went 12-1 in Vinny Testaverde’s thirteen starts, and finished in the top five of the league in points, yards, and first downs. That season, Curtis Martin received 369 carries despite missing one game due to injury. Martin rushed 25+ times in seven games and recorded at least 17 carries in every game that year… and averaged only 3.49 yards per carry. There are some who would have you believe that the Hall of Fame head coach didn’t quite know what he was doing that year, and the Jets would have been even better had the team called Martin’s number less frequently.

[continue reading…]

The team’s top two offensive players in 2012 were left tackle Jared Veldheer and quarterback Carson Palmer. Palmer is now in Arizona, while Veldheer is out indefinitely with a torn triceps. Brandon Myers (Giants) and Darrius Heyward-Bey (Colts) are also gone, and they combined for 29 starts last season. The big free agent signings were S Charles Woodson (Green Bay), LB Kevin Burnett (Miami), QB Matt Flynn (Seattle), CB Mike Jenkins (Dallas), CB Tracy Porter (Denver).

As a result, there’s little optimism in Oakland entering the season. The Raiders are one of the favorites to land the first pick in the 2014 draft, so the 2013 season will likely be used to see what building blocks actually exist in Oakland. After Terrelle Pryor outplayed Flynn in the preseason, many now think the Raiders going to start Pryor in week 1 because, well, why not? If that’s the case, we’ll have another example to test out a theory that’s widely-accepted by conventional analysts.

[continue reading…]

I don’t know if that’s true, but let’s investigate. First, I’m only giving a running back credit for his additional carries after his 15th carry of the game. So an 18-carry game goes down as a “3” and a 25 carry game is a “10.” Using this scoring system, Arian Foster had the highest number of “Carries over 15” from last season, with 117. Such a list mostly corresponds to the number of overall rushing attempts for a player, but the exceptions could be revealing.

[continue reading…]

Yesterday, I set up a method for ranking the flukiest fantasy football seasons since the NFL-AFL merger, finding players who had elite fantasy seasons that were completely out of step with the rest of their careers. I highlighted fluke years #21-30, so here’s a recap of the rankings thus far:

30. Lorenzo White, 1992

29. Dwight Clark, 1982

28. Willie Parker, 2006

27. Lynn Dickey, 1983

26. Robert Brooks, 1995

25. Ricky Williams, 2002

24. Jamal Lewis, 2003

23. Mark Brunell, 1996

22. Vinny Testaverde, 1996

21. Garrison Hearst, 1998

Now, let’s get to…

The Top Twenty

20. RB Natrone Means, 1994

| Best Season | ||||||||

| year | g | rush | rushyd | rushtd | rec | recyd | rectd | VBD |

| 1994 | 16 | 343 | 1,350 | 12 | 39 | 235 | 0 | 103.0 |

| 2nd-Best Season | ||||||||

| year | g | rush | rushyd | rushtd | rec | recyd | rectd | VBD |

| 1997 | 14 | 244 | 823 | 9 | 15 | 104 | 0 | 12.9 |

Big, bruising Natrone Means burst onto the scene in 1994 as a newly-minted starter for the Chargers’ eventual Super Bowl team, gaining 1,350 yards on the ground with 12 TDs. In the pantheon of massive backs, he was supposed to be the AFC’s answer to the Rams’ Jerome Bettis, but Means was slowed by a groin injury the following year and never really stayed healthy enough to recapture his old form. The best he could do was to post a pair of 800-yard rushing campaigns for the Jaguars & Chargers in 1997 & ’98 before retiring after the ’99 season.

19. WR Braylon Edwards, 2007

| Best Season | |||||

| year | g | rec | recyd | rectd | VBD |

| 2007 | 16 | 80 | 1,289 | 16 | 107.7 |

| 2nd-Best Season | |||||

| year | g | rec | recyd | rectd | VBD |

| 2010 | 16 | 53 | 904 | 7 | 15.4 |

The 3rd overall pick in the 2005 Draft out of Michigan, Edwards seemingly had a breakout 2007 season catching passes from fellow Pro Bowler Derek Anderson. But both dropped off significantly the next season, and Edwards was sent packing to the Jets in 2009. He did post 904 yards as a legit starting fantasy wideout in 2010, but he has just 380 receiving yards over the past 2 seasons, and it’s not clear he’ll ever live up to those eye-popping 2007 numbers again.

[continue reading…]

Two house-keeping notes before we get to today’s post. First, today’s a pretty big day for our friend Neil Paine: he’s getting married. I’ll be there to celebrate with him in Philadelphia, but I know you guys will be with us in spirit. Congrats to Kaitlyn and Neil!

And another set of confetti must be reserve for the seven members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame Class of 2013: Larry Allen, Cris Carter, Jonathan Ogden, Warren Sapp, Curley Culp, Dave Robinson, and Bill Parcells. Tonight, those men will be inducted into the Hall of Fame, a must-see event for any football fan.

Today’s post focuses on one player already enshrined in Canton and one future Hall of Famer. As a general disclaimer, it’s best not to take too seriously what comes out of the mouths of football players, especially this time of year. That said, Adrian Peterson, part-cyborg, part-Minnesota Vikings running back, recently told Dan Wiederer of the Minneapolis Star Tribute that he thinks he will break Emmitt Smith’s career rushing record:

Q Forget about Eric Dickerson’s record for a minute. Last December, we talked about Emmitt Smith’s record and I told you you were on pace to get there in Week 4 of 2019. You said sooner and promised to come back with a timetable. Emmitt had 18,355 yards. You’re now 9,506 away. We need a week and a year. When do you get there?

A Man. Oh boy. I have to do some calculations. I’ve been in the league seven years. I’m already right around [9,000]. Calculate it out … Let’s think. Maybe get a couple 2,000 yard seasons … I’ve got … Hmmm … 2017.

Q What week in 2017?

A Man. I better go late. I’m already getting too far in front of myself. I’ll say Week 16. There it is. Week 16 in 2017. Whoo. That’s pushing it, huh? But hey, pushing it is the only way to do it. You know it.

Just to break it down for you in full, that gives Peterson 79 games to amass the 9,506 yards he needs to reach Smith. That comes out to a per-game average of 120.3 yards per contest with the assumption that Peterson avoids injury and doesn’t miss a game between now and Week 16 of 2017. Yes, it’s pushing it indeed. But good fun to consider, right?

Let’s talk reality. Peterson has rushed for 8,849 rushing yards in his six-year career, and was 27-years-old last year. The first problem for Peterson is that he was 937 yards behind Smith’s pace before Peterson even entered the league. That’s because Peterson, born in March, entered the league at 22, while Smith, born in May, entered at age 21. Unless you think we should compare the two by seasons and not age — and more on why that’s a bad idea later — we need to give Smith full credit for one extra year. In fact, here’s a chart comparing the two players in career rushing yards through age X. Smith also rushed for slightly more yards from ages 22 to 27 (9223-8849) than Peterson, but when you factor in his age 21 performance, Smith has a big lead on Peterson through age twenty-seven. You might recall I presented a similar chart when comparing Jason Witten to Tony Gonzalez and Jerry Rice.

[continue reading…]