Bryan Frye is back with another fun guest post. Bryan, as you may recall, owns and operates his own great site at http://www.thegridfe.com/, where he focuses on NFL stats and history. You can view all of Bryan’s guest posts at Football Perspective at this link. You can follow him on twitter @LaverneusDingle.

Fans familiar with the history of the NFL know that Fritz Pollard and Bobby Marshall were the first black NFL players, playing in the league’s inaugural season of 1920. [1]For its first two seasons, the NFL was known as the American Professional Football Association, or APFA. It didn’t become the National Football League until 1922. However, often lost in history is the story of the first recorded black professional football player: Charles Follis.

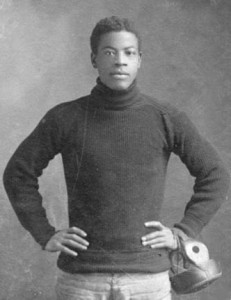

Follis’ name rarely comes up because he played well before the inception of the NFL, before Americans had even heard of Jim Thorpe. When Follis first played professionally, Pollard was only ten years old, and Marshall was just a freshman at Minnesota. The year was 1904 – when Teddy Roosevelt was more interested in negotiating treaties between Japan and Russia than he was in saving football – and the twenty-five year old “Black Cyclone” inked a meager deal with the Shelby Blues of the Ohio League. However, Follis was more than a footnote in football history, and his story merits another telling.

Follis was born in Virginia in 1879, the oldest of seven children. His father was a farm laborer, which effectively meant Charles was, too. He worked long hours with his father, developing great strength at a young age. [2]This reminds me of the well-known story of Jerry Rice working countless hours with his bricklaying father, catching brick after brick after brick that his father tossed to him. It is unclear when the family left Virginia for Wooster, Ohio, but interviews suggest that it was when Follis was still a small child. [3]From Milt Roberts’ 1975 interview with Follis’ sister-in-law, Florence Follis.

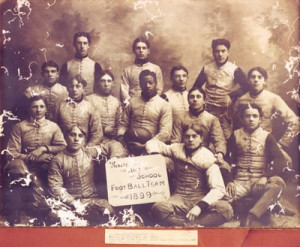

As a junior in high school in 1899, he not only led the effort to establish Wooster High School’s first football team, but he was also subsequently elected team captain by his white teammates. He was the team’s star player as they went undefeated, not allowing a point all season. So great was his impact on Wooster High School that the school’s football stadium was named Follis Field in 1998. His prowess in both football and his best sport, baseball, were so easily recognizable that he was eagerly recruited by the local college.

In the days before the NCAA, eligibility rules were almost comically lenient for college athletes. Despite never actually matriculating in the University of Wooster (now the College of Wooster), Follis began playing for the school’s baseball team at the age of 22. However, he decided to forego playing for the college football team. Instead, Follis played for the Wooster Athletic Association, which was a local amateur club that traveled to play other amateur teams.

F.C. Schieffer [4]I’ve also seen this written as Scheffer and Schiffer, but the spelling I used is the most common. was the manager of the Shelby Blues, a team that had faced and defeated Wooster twice before. However, Follis’ performance in those losses led to Schieffer recruiting him to play for the Blues in 1902. In order to allow Follis to focus on playing football, the manager set him up with a job at a local business, Howard Seltzer and Sons Hardware Store; the shop owner agreed to give Follis plenty of time to practice and play football (thus, while he was not technically paid to play in 1902, he was practically paid to play).

While Schieffer favored Follis, many white players – teammate and opponents alike – disdained him. In addition to avoiding him on the field, some teammates refused to travel with him. Opponents were even worse: when the Blues played away games, opposing players would often spit in his face, kick him, or stomp on him. [5]Obviously, this was not universal behavior. For instance, the Toledo Evening News Bee reported that the team captain of Toledo, Jack Tattersall, petitioned his home crowd not to berate Follis, … Continue reading If you’ve seen just about any movie on the topic of integrating sports, you’re probably familiar with similar stories. However, most firsthand accounts agree that real life was often much worse than its artistic portrayal. [6]While Follis was certainly a better baseball player than football player, his most significant contribution to baseball may have been his influence on Branch Rickey, who was a baseball star at Ohio … Continue reading

Despite experiencing such contempt, Follis demonstrated grace and poise both on and off the field, and Schieffer rewarded him for it. In 1904, the Blues signed him to a professional contract worth ten dollars per game, unknowingly making him the first black professional football player. [7]Credit researchers John Seaburn and Milt Roberts for uncovering this information. In 1975, the two found information in the Shelby Daily Globe indicating Follis signed professionally in 1904. … Continue reading According to newspaper reports from the era, Shelby’s investment in Follis paid off. He was a devastating tackler, adept at using speed or strength to beat opponents. On offense, he was recorded with several long plays on the season, including an 83 yard touchdown run in the 1904 season opener. Ultimately, he led the Blues to an 8-1-1 record, with the team’s only loss coming at the hands of the undefeated league champion Massillon Tigers. [8]If you’re not sure why that name sounds familiar, Massillon is one of the most famous football towns in the country. Massillon Washington High School is as well-known as high school football … Continue reading

Unfortunately, both the game and the world were much different back then. Football was much more dangerous (it resulted in 18 deaths in 1905 alone) [9]Many players actually drowned in mud when trapped at the bottom of a scrum., and both medicine and technology were primitive compared to what we have today. Playing a violent game without good medical treatment or career-preserving technology generally meant that football careers were much shorter, and their immediate effects much more pronounced. On Thanksgiving Day, 1906, Follis “limped off the field for the last time” [10]Ed Arn’s lamentation in his book Black and Gold: The History of College of Wooster Athletics, 1870-1945. at the mere age of 27.

Although his body was too broken to continue with football, he was able to keep playing baseball at the professional level. While playing baseball in Cleveland for the Cuban Giants in 1910, Follis caught pneumonia. He succumbed to the illness on April 5, at the age of 31. His obituary dubbed him “one of the greatest baseball players that ever lived.” [11]The Wooster Republican, April 6, 1910.

The record keeping from the antediluvian days of football is lamentably wanting, so we have little to no way of knowing the whole story of his statistical impact. We know from old newspaper articles that he had several long touchdown runs and that he was anecdotally a great defender, but that is about all we know. When dealing with players from that long ago, we are almost forced to traffic in narrative and myth-making. For one reason or another, the passage of time has all but removed Follis from the game’s narrative, and he has certainly not reached the pantheon of mythic figures from the game’s early days. [12]There are many possible explanations, such as the rather low status of football in American society at the time, or the fact that no one knew he was the first black pro until 65 years after his … Continue reading Whatever the reason, it is important that we not sweep his story under the rug. Pollard and Marshall are rightly remembered as pioneers. Lowell Perry and Art Shell, too. When we remember their names, let’s also remember the name Charles Follis.

References

| ↑1 | For its first two seasons, the NFL was known as the American Professional Football Association, or APFA. It didn’t become the National Football League until 1922. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This reminds me of the well-known story of Jerry Rice working countless hours with his bricklaying father, catching brick after brick after brick that his father tossed to him. |

| ↑3 | From Milt Roberts’ 1975 interview with Follis’ sister-in-law, Florence Follis. |

| ↑4 | I’ve also seen this written as Scheffer and Schiffer, but the spelling I used is the most common. |

| ↑5 | Obviously, this was not universal behavior. For instance, the Toledo Evening News Bee reported that the team captain of Toledo, Jack Tattersall, petitioned his home crowd not to berate Follis, calling Follis “a gentleman and a clean player.” However, such interventions were uncommon. It is important to note, I think, that Follis eventually won over his teammates with his play and his character. |

| ↑6 | While Follis was certainly a better baseball player than football player, his most significant contribution to baseball may have been his influence on Branch Rickey, who was a baseball star at Ohio Wesleyan University at the same time Follis was at Wooster. Apparently, they were the two top catchers in the area, in addition to overlapping on gridiron with the Blues. Therefore, Follis and Rickey played the part of both teammates and opponents, but they ultimately became good friends. Rickey respected and admired Follis, especially for his ability to persevere in the face of such wanton racism. It has been suggested that Rickey, the Brooklyn Dodgers general manager largely responsible for signing Jackie Robinson to reintegrate professional baseball in 1947, believed in the idea of desegregation, in part, because of his time with Follis. |

| ↑7 | Credit researchers John Seaburn and Milt Roberts for uncovering this information. In 1975, the two found information in the Shelby Daily Globe indicating Follis signed professionally in 1904. Separate research conducted by the Pro Football Hall of Fame uncovered evidence that Shelby may have been a professional team in 1902, but 1904 is the earliest year of which this is a certainty. |

| ↑8 | If you’re not sure why that name sounds familiar, Massillon is one of the most famous football towns in the country. Massillon Washington High School is as well-known as high school football teams can get, and also where Paul Brown began his coaching career. You might recall the Massillon Tigers because in 1906, the Tigers and Canton Bulldogs got caught up in professional football’s first major gambling scandal. |

| ↑9 | Many players actually drowned in mud when trapped at the bottom of a scrum. |

| ↑10 | Ed Arn’s lamentation in his book Black and Gold: The History of College of Wooster Athletics, 1870-1945. |

| ↑11 | The Wooster Republican, April 6, 1910. |

| ↑12 | There are many possible explanations, such as the rather low status of football in American society at the time, or the fact that no one knew he was the first black pro until 65 years after his death, but the most plausible is that he played too briefly and was ultimately known for baseball. Even his obituary, which touted his baseball achievements, made no mention of football at all. |