In his first playoff game, Drew Brees threw a game-tying touchdown pass to Antonio Gates with 11 seconds remaining to force overtime against the Jets. In overtime, Brees and the Chargers drove 48 yards down the field, and converted two third downs, to set up a game-winning 40-yard field goal. Unfortunately for Brees, Nate Kaeding missed the kick, and the Jets won in overtime.

In his second playoff game, Brees had an efficient performance in a win over the Eagles. The next week, New Orleans faced an excellent Bears team in frigid conditions in Chicago. Brees’ teammates lost two fumbles, rushed for a total of 48 yards, and allowed 37 points in an NFCCG loss.

Brees’ next three playoff games were all in 2009, when he threw 8 touchdowns and no interceptions as the Saints won the Super Bowl.

His next playoff game? That was the BeastQuake game when Marshawn Lynch rumbled for a 67-yard touchdown in the 4th quarter. The Saints lost 41-36, despite Brees throwing for 404 yards and 2 touchdowns with no interceptions. This would not be the last time Brees would lose a game despite his team scoring over 30 points.

The next playoff game of his career was his best, at least statistically. Even with era and defensive adjustments, it ranked as one of the 10 best passing games in postseason history: He threw for 466 yards and 3 TDs on 43 attempts in a 45-28 win over the Lions.

The next week Brees lost in one of the classic games in modern postseason history. Take a look at the boxscore:

This was the first game in playoff history with four lead changes in the final five minutes. Brees had a monster game against a great 49ers pass defense, and gave his team the lead in the final two minutes. Alas, that was not enough. This would not be the last time that would happen, either.

Two years later, Brees and the Saints won in Philadelphia as underdogs. This was, statistically, the worst playoff game of his postseason career. On the other hand, he and the Saints were a dome team playing a night game in Philadelphia in freezing conditions, and after a rough first half, the Saints scored two touchdowns and two field goals in five second half possessions. On the final drive, he picked up two first downs to set up the game-winning field goal.

The next week wasn’t good: he was 24/43 for 309 yards and 1 TD which oh wait it was against the 2013 Seahawks. In Seattle. So yeah, that was a pretty good game in a losing effort.

That brings us to 2017. In the first round of the playoffs, Brees went 23/33 for 376 yards and 1 TDs in a 31-26 win over Carolina. And then yesterday against the Vikings? After a miserable first half, Brees and the Saints scored three touchdowns on the team’s first four drives of the second half. The final touchdown put New Orleans ahead by 1 point with 2:20 to go.

Minnesota answered with a 9-play, 40-yard drive that culminated with a 53-yard field goal. New Orleans got the ball back, down 2 with 89 seconds left and one timeout, and drove 50 yards for the field goal. The Saints took a 24-23 lead with 25 seconds remaining.

With 10 seconds remaining, the Vikings had the ball at their own 39 yard line with no timeouts left. And then this happened:

Well, this happened:

One of the greatest plays in playoff history. An instant classic. And yet, once again, Brees was left holding the short straw. Does this boxscore look familiar?

There have been two games in NFL postseason history with four lead changes in the final five minutes. And Brees was on the losing end in both of them.

As a reminder, in 13 playoff games:

- The other team has scored 28+ points 6 times, and Brees is 2-4 in those games This includes the only two games in playoff history with four lead changes in the final five minutes and the BeastQuake game where the Saints scored 36 points.

- Brees’ teams are 5-2 when the opponent scores under 28 points. The two losses include a game against one of the best pass defenses in NFL history and a game where his kicker missed a 40-yard field goal in overtime.

- The average score of a Drew Brees playoff game is 28.8 to 26.8. While with the Saints, that jumps to 29.8 to 27.4.

In the last 10 postseasons, there have been 27 games with at least 56 points combined (i.e., an average of 28 points per team). Brees’s Saints have been involved in six of those 27 games. Keep in mind that there have been 214 playoff games over that stretch, and New Orleans has only been in 10 of them.

That means 60% of all Drew Brees playoff games see 56+ points scored, compared to 10% of all other games.

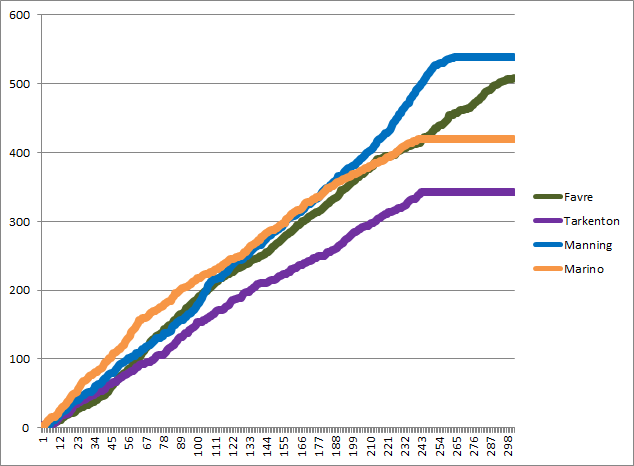

Brees is one of just four quarterbacks with a career passer rating in the playoffs over 100 and has averaged 324 passing yards per game in the playoffs, easily the most of all time. His stat line — 354/537, 4,209 yards, 29 TDs, 9 INTs, 100.7 passer rating, 22 sacks — looks like that of an MVP candidate, especially when you consider that’s in only 13 games. Pro-rated to 16 games, and it’s 5,180 yards with 36 TDs and 11 INTs on 661 attempts. Those are nearly identical to the numbers he put up in an MVP caliber 2013 season.

In other words, Drew Brees in the playoffs plays like the best version of Drew Brees in the regular season, which is pretty darn incredible. But what’s even more incredible is the string of events that have left him with just a 7-6 record. For that 7-6 record, he can thank Kaeding, Lynch, Vernon Davis, Stefon Diggs, and going up against two of the best defenses of the last 15 years.