Today’s guest post comes from James “Four Touchdowns” Hanson, a relative new reader to the site. As always, we thank our guest posters for contributing.

[Editor’s note: There were a couple of minor bugs in the original data. This post has now been updated.]

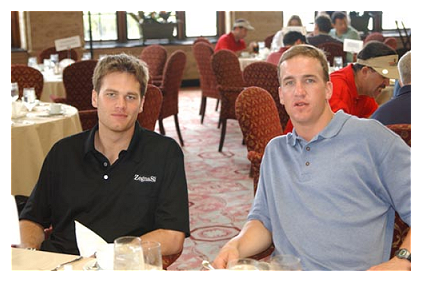

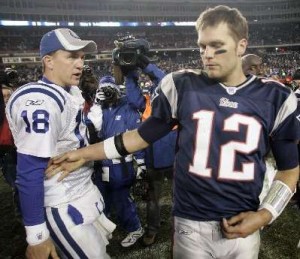

There may be no two quarterbacks more often measured against each other than Tom Brady and Peyton Manning. One simply has to do a Google search of the topic to see that fans and sports writers have compared the two numerous times, using a vast array of criteria from the simple counting of championships to using advanced analytics to make their case.

So it’s surprising to me that I still haven’t come across a comparison of Manning and Brady against the same defenses. It’s an idea that occurred to me when Manning critics pointed out that much of his record-breaking 2013 season came against the mediocre teams of the 2013 NFC East and AFC South, while Tom Brady’s record-breaking 2007 was against a tougher strength-of-schedule. If we’re genuinely after the fairest assessment possible – which is why I assume fans of advanced analytics prefer to measure individual players by their own production rather than team results like wins and championships – what better way to measure each player than by how they performed against the same competition?

So I decided to take a look at the seasons in which Manning and Brady were both active and played against the same teams in the same season. Of course, like any statistical analysis, this one comes with its own set of flaws. When the two quarterbacks play each other’s divisions or one plays the same team in the regular season and the playoffs, one of them may have played the same team twice or even three times in a single season while the other has played them only once.

This can be good or bad for the player’s results – sometimes it allows the opposing defense to learn from the first encounter and make life difficult for the passer the second time around. One example is Peyton Manning’s encounters with the Steelers in 2005; he defeated Pittsburgh with a 102.9 rating and 8.67 ANY/A during the regular season, only to see his performance suffer the second time around during the post-season with a 90.9 rating and 6.21 ANY/A in a loss. Meanwhile, Tom Brady’s single game against the Steelers, where he won with a 92.7 rating and 6.84 ANY/A, stands alone – could he have done better or worse in a second encounter? We’ll never know.

Other times, it can allow the quarterback another opportunity to do well against that defense. When Brady played the Jets for the first time in 2010, he earned a mediocre 72.9 rating and 5.11 ANY/A in a loss. He bounced back to win with an extraordinary 148.9 rating and 12.00 ANY/A in their second meeting and then fell somewhere in between when they met in the playoffs, losing with an 89 passer rating and 5.08 ANY/A. Meanwhile, Manning met the Jets just once in the post-season, where he suffered a loss despite earning a 108.7 rating and 8.85 ANY/A in his last game wearing a Colts uniform. How would he have done if he played the Jets three times? Again, we’ll never know.

In fact, the sometimes vast difference in which each QB has performed against the same defense in the same season should encourage us to take these results with a grain of salt – in-game conditions, game plans from coaches, the play from supporting casts, how one team’s strengths and weaknesses match differently with an opponent, playing at home or away, key injuries on either side, etc. can all effect a player’s performance in any given game.

And there’s always the possibility that Brady or Manning just had a bad day and their performance isn’t indicative of their true abilities: the small sample size of a football season made even smaller by singling out common opponents isn’t ideal in determining a fair and scientific measurement for how good each player actually is. On the other hand, it’s the only evidence we have available, so we’ll have to roll with it.

I bring this up because I don’t intend this to be a definitive attempt at determining which player is better – most people already have made up their minds (and I personally tend to rate quarterback on tiers anyway). Some say Manning would have more championships if he had Belichick and the Patriots organization at his side, while others say Brady would have bigger numbers if he had the receiving talent Manning had during his career. I think both can be true.

I’d also like to mention that I pulled this list manually and despite several reviews, there still may be errors in the data – this is unintentional and I welcome any corrections.

So without further ado, here’s a list of the common opponents they faced in each season, with both 2008 (Brady played one game) and 2011 (Manning was inactive) removed as both players weren’t active during those seasons:

• 2001: Jets, Bills, Dolphins, Raiders, Saints, Falcons, Broncos, Rams

• 2002: Dolphins, Jets, Steelers, Titans, Broncos

• 2003: Dolphins, Jets, Bills, Browns, Broncos, Jags, Texans, Titans, Panthers

• 2004: Ravens, Chiefs

• 2005: Steelers, Jaguars, Chargers

• 2006: Bills, Jets, Dolphins, Titans, Jags, Texans, Broncos, Bengals, Bears

• 2007: Chargers, Ravens, Jaguars

• 2009: Bills, Jets, Dolphins, Titans, Jags, Texans, Ravens, Broncos, Saints

• 2010: Chargers, Jets, Bengals

• 2012: Texans, Ravens

• 2013: Colts, Ravens

• 2014: Bills, Jets, Dolphins, Raiders, Chiefs, Chargers, Colts, Bengals, Seahawks

• 2015: Colts, Steelers, Chiefs

And here are their career averages against common opponents from 189 total regular season and playoff games played (93 Manning, 96 Brady):

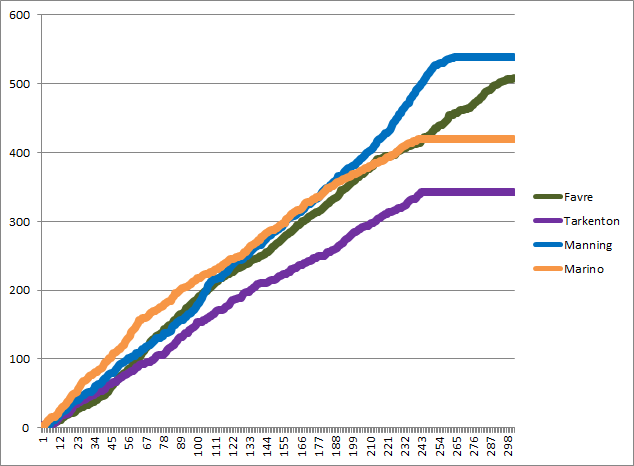

Except for interception percentage, Manning seems to have a slight advantage across the board. Most differences are so small that I personally consider them basically even in most categories. The biggest differences seem to be that Manning’s interception rate is substantially higher, while Brady’s sack numbers are substantially higher – and in Brad Oremland’s TSP and Career Value metrics, where Manning holds a commanding lead.

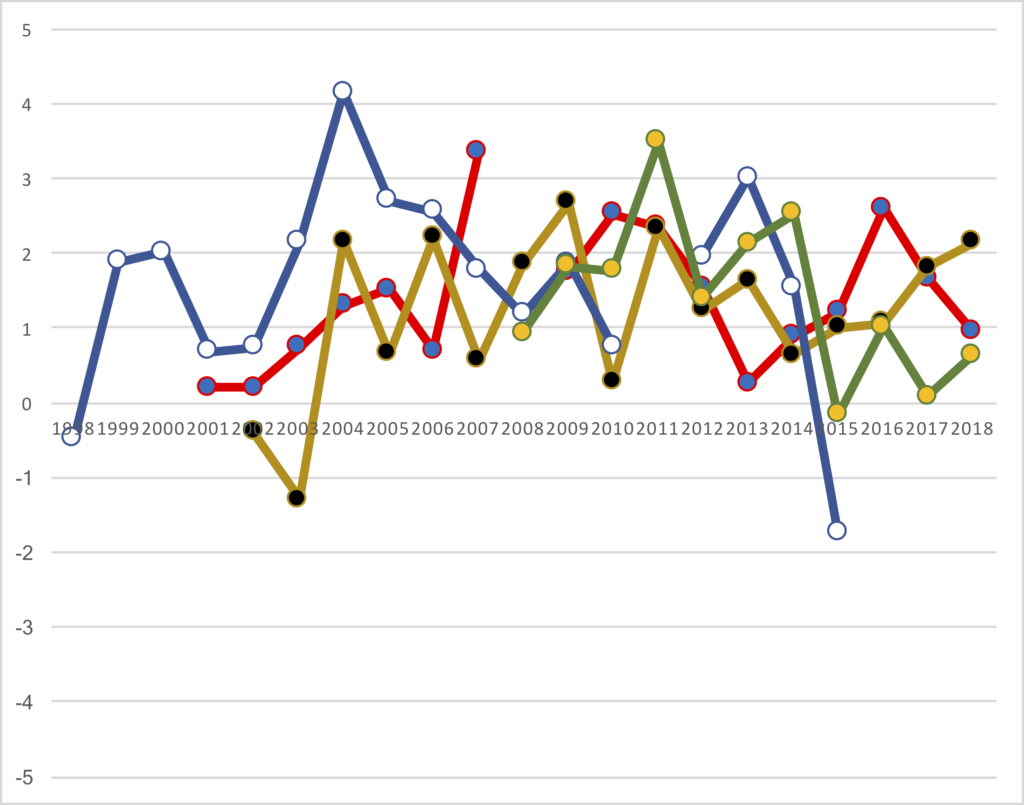

To delve a little further into the numbers, let’s look at the advanced stats of each player by season. The highlights indicate which player did better that year in each metric, while the bolded numbers indicate that season’s number marks a career best (against common opponents) –

The leader in both ANY/A and Passer Rating match in every season, with Manning’s rates beating Brady’s in 8 of the 13 seasons compared. QBR results are also is very similar, with the only difference being Brady having the edge in 2014, putting them even at 4-4.

Interestingly, it seems that for most seasons, one player clearly played better against common opponents by a substantial amount – in Passer Rating, the two only play at a similar level in 2001 and 2007, while the rest of the time the winner often beats the other by ten points or more! What’s really surprising to me is that Manning surpasses Brady in every metric for 2007, which was when Brady led perhaps the greatest offense of all time to a record-breaking season and an AFC Championship.

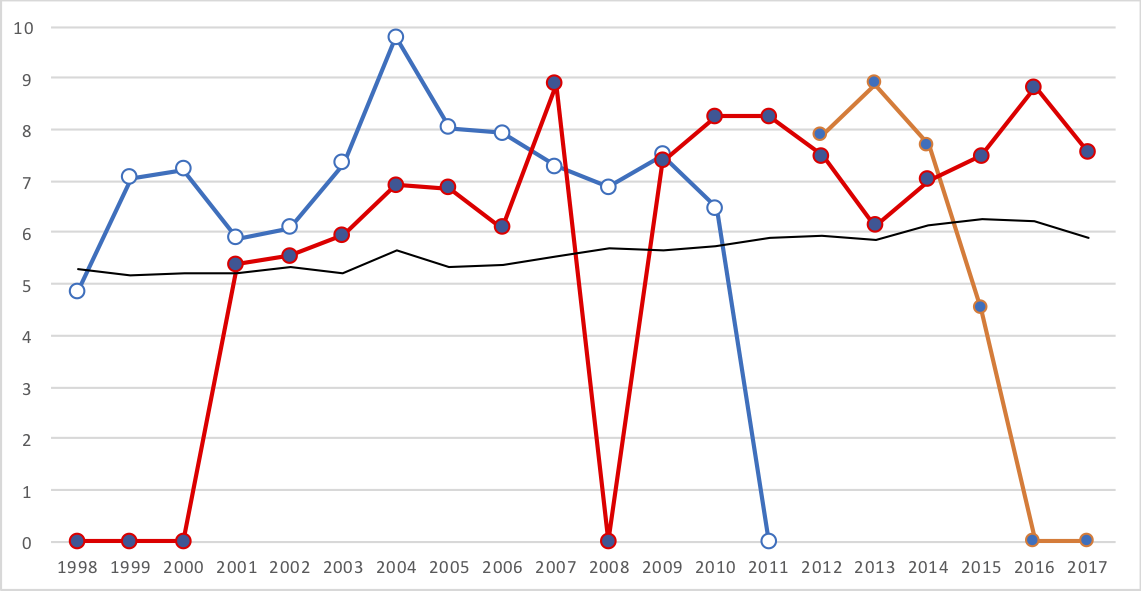

I also wanted to compare their performances against common opponents in each season by TSP but since it’s a raw sum instead of an average like the other advanced stats, I needed to take each season’s statistical averages and multiply them to get 16 games worth of production. The results were –

The first thing that jumps out at you is Manning’s preposterous 2013 prorated across 16 games – over 6,500 yards and 75 TDs with only 5 INTs. That alone tells us to take these results with a grain of salt.

But accepting the numbers for what they are, we see that the leader in TSP for each season matches the leader in Passer Rating and ANY/A. We also see that Manning’s highs and lows are quite extreme in comparison to Brady’s – Brady doesn’t have a season that matches Manning’s 2004 and 2013, but Brady’s TSP never dips into negative numbers as Manning’s does in 2002 and 2015.

And again, Manning’s 2007 results manage to top Brady’s numbers for his most legendary statistical season (though that probably means nothing since the sample size we’re working with is so small).

So what does this all prove? Well, nothing really. As said, I think the majority of people already have their opinions set for these players – this is just for fun. Hope you enjoyed!