As you probably know, the NFL is announcing its top 100 players in league history as part of its 100-year anniversary. The nominating committee selected 24 running backs as finalists, and with the exception of active RB Adrian Peterson, every player is in the Hall of Fame. For the final team, 12 running backs were chosen. The table below shows the finalists and those selected for the official team:

| Player | Teams | First Yr | Last Yr | Selected? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch Clark | Portsmouth Spartans/Detroit Lions | 1931 | 1938 | Selected |

| Steve Van Buren | Philadelphia Eagles | 1944 | 1951 | Selected |

| Marion Motley | Cleveland Browns; Pittsburgh Steelers | 1946 | 1955 | Selected |

| Jim Brown | Cleveland Browns | 1957 | 1965 | Selected |

| Lenny Moore | Baltimore Colts | 1956 | 1967 | Selected |

| Gale Sayers | Chicago Bears | 1965 | 1971 | Selected |

| O.J. Simpson | Buffalo Bills; San Francisco 49ers | 1969 | 1979 | Selected |

| Walter Payton | Chicago Bears | 1975 | 1987 | Selected |

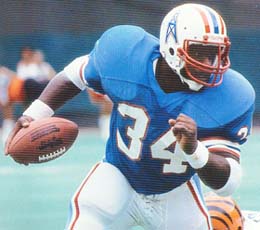

| Earl Campbell | Houston Oilers; New Orleans Saints | 1978 | 1985 | Selected |

| Eric Dickerson | Los Angeles Rams; Indianapolis Colts; Los Angeles Raiders; Atlanta Falcons | 1983 | 1993 | Selected |

| Barry Sanders | Detroit Lions | 1989 | 1998 | Selected |

| Emmitt Smith | Dallas Cowboys; Arizona Cardinals | 1990 | 2004 | Selected |

| Marcus Allen | Los Angeles Raiders; Kansas City Chiefs | 1982 | 1997 | Finalist |

| Jerome Bettis | Los Angeles/St. Louis Rams; Pittsburgh Steelers | 1993 | 2005 | Finalist |

| Tony Dorsett | Dallas Cowboys; Denver Broncos | 1977 | 1988 | Finalist |

| Marshall Faulk | Indianapolis Colts; St. Louis Rams | 1994 | 2005 | Finalist |

| Red Grange | Chicago Bears; New York Yankees | 1925 | 1934 | Finalist |

| Franco Harris | Pittsburgh Steelers; Seattle Seahawks | 1972 | 1984 | Finalist |

| Hugh McElhenny | San Francisco 49ers; Minnesota Vikings; New York Giants; Detroit Lions | 1952 | 1964 | Finalist |

| Bronko Nagurski | Chicago Bears | 1930 | 1943 | Finalist |

| Adrian Peterson | Minnesota Vikings; New Orleans Saints; Arizona Cardinals; Washington Redskins | 2007 | 2019 | Finalist |

| Jim Taylor | Green Bay Packers; New Orleans Saints | 1958 | 1967 | Finalist |

| Thurman Thomas | Buffalo Bills; Miami Dolphins | 1988 | 2000 | Finalist |

| LaDainian Tomlinson | San Diego Chargers; New York Jets | 2001 | 2011 | Finalist |