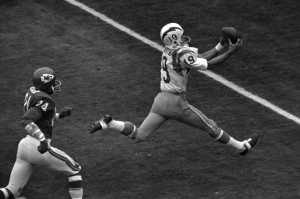

One of many Rams greats to wear #29.

As you guys know, Neil Paine is

the man. Here’s the latest reason: he came up with a metric called True Receiving Yards, the latest in a long line of thoughts in our

Wide Receiver Project. So, what are True Receiving Yards?

We start with Adjusted Catch Yards, defined as 5 * Receptions + Receiving Yards + 20 * Receiving Touchdowns.

1) Then, we convert each player’s Adjusted Catch Yards to the same scale as pure receiving yards using the following formula:

Adjusted Catch Yards * League Receiving Yards / League Adjusted Catch Yards

2) Next, we adjust for how often the receiver’s team passed. We use the following formula:

[Result in Step 1] * League_Avg_Team_Pass_Attempts / Team_Pass_Attempts

For purposes of this post, Team Pass Attempts include sacks.

3) Then we adjust for the league passing environment, by using this formula:

[Result in Step 2] * by (214.54/Avg_Team_Receiving_Yards_Per_Game).

Why 214.54? Because that’s how many yards the average NFL team has passed for in each season since 1970.

4) Finally, we need to adjust for schedule length. This one’s pretty simple:

[Result in Step 2] * 16 / Team Games

As it turns out, the single-season leader in True Receiving Yards is….. Harold Jackson for the 1973 Rams. That will probably surprise some folks; heck, it surprised me. So let’s walk through Jackson’s season by comparing it to Calvin Johnson’s 2012. Jackson caught 40 passes for 874 yards and 13 touchdowns. That gives him 1,334 Adjusted Catch Yards, while Megatron’s 122-1964-5 translates to 2,674 Adjusted Catch Yards, more than twice what Jackson produced.

1) First, we need to convert those ACY numbers into receiving yards. In 1973, that conversion ratio is 65.5%, and in 2012, it was 64.5%; this means Jackson is credited with 874 receiving yards (ironically, his actual number) while Johnson is pushed down to only 1,725 yards. This is because Johnson had a ton of yards but only five touchdowns. In other words, based on his receptions, receiving yards, and receiving touchdowns, Johnson was more like a 1,725-yard receiver last year.

2) Jackson’s Rams had just 288 Team Pass Attempts, while the average team in 1973 averaged 373.3 pass attempts. So we need to bump Jackson up by 29.6%, which would give him 1,132 receiving yards. The 2012 Lions had 769 Team Pass Attempts compared to a league average of 592.4; therefore, we need to give Johnson credit for only 77% of his ACY, bringing him down to 1,329 receiving yards.

3) Next, we adjust for league environment. In 1973, the average team passed for 159 yards per game, which means we need to bump Jackson up by 34.6% (the result of 214.54 divided by 159); this gives him 1,524 receiving yards. For Megatron, since the average team in 2012 passed for 246 yards per game, we need to multiply his result in step 2 by 87.2%, leaving him with only 1,159 receiving yards.

4) For Calvin Johnson, that’s it: he is credited with 1,159 True Receiving Yards, after reducing his numbers for playing in a pass-happy offense, playing in a pass-happy era, and not having many touchdowns. For Jackson, his 1,524 gets pro-rated to a 16-game season, giving him 1,742 True Receiving Yards.

[continue reading…]