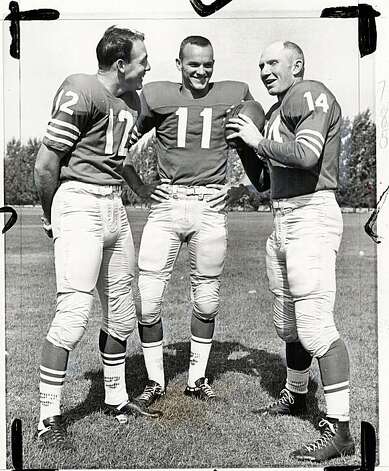

Brodie (left) and Tittle (right) on the 49ers. Photo by Associated Press/1960 Photo: 1960, Associated Press.

I thought it would be interesting to see if certain statistics could help identify teams that ran a West Coast Offense. My initial thought was that an effective West Coast Offense would manifest itself in three key statistics:

- Completion percentage. The WCO is built around short passes that work as a substitute for running plays. These long handoffs lead to high completion percentages for the quarterback.

- Yards per completion. Short passes imply lower yards per completion. Ideally, we’d analyze yards per completion after removing yards after the catch, but that’s not something the NFL kept records of historically. Still, I think a low yards per completion average can be a good indicator that a team ran a West Coast Offense.

- Passing first downs. In a West Coast Offense, teams are moving the chains through the air. With fewer long gains and a pass-first mentality, one would expect a lot of passing first downs.

Background

If you’re a historian, you can skip this section. The classic story told about the birth of the West Coast Offense takes us back to before the AFL-NFL merger. In 1969, the Bengals had Paul Brown as head coach and Bill Walsh as the assistant coach/offensive coordinator. That year, quarterback Greg Cook had one of the great rookie seasons in history, but injuries to his rotator cuff and biceps ruined his career. The team turned to backup Virgil Carter, a very smart and accurate passer but who was destined to be a backup because of his size and weak arm. Those factors led Walsh and Brown to implement an offense that catered to Carter’s strengths and hid his weaknesses.

Carter wasn’t just smart for football. In 1970, he published a seminal paper that was the precursor to the Expected Points models we see today; in ’71, Carter led the NFL in completion percentage, but ranked third to last among the 21 qualifying quarterbacks in yards per completion. The Bengals ranked 9th in passing first downs, and those statistics seem to jive with the picture we all have in our heads of a West Coast Offense.

Of course, Walsh’s offense really took form in San Francisco. In his first year with the 49ers, the team went 2-14 with Steve DeBerg at quarterback. Despite the record, San Francisco still led the NFL in passing first downs and finished in the top three in completion percentage and the bottom three in yards per completion. The next year, Joe Montana’s first year as a starter, Montana ranked 30th among 30 qualifying quarterbacks in yards per completion but 1st in completion percentage, as San Francisco ranked 9th in passing first downs. Walsh and Montana won their first Super Bowl in ’81: that year, Montana finished 1st in completion percentage and second-to-last in yards per completion, as San Francisco ranked 5th in passing first downs.

All of those numbers are background and supporting evidence to suggest that the three statistics I’ve selected serve as good proxies for measuring whether a team has a WCO-style offense.

Before The West Coast Offense

Before Montana finished 1st in completion percentage and last in yards per completion in 1980, four other quarterbacks pulled off that some feat: Sonny Jurgensen in 1969, John Brodie in ’58, Y.A. Tittle in ’57, and Bobby Thomason in 1951. But it’s Tittle and Brodie who caught my eye. [1]Why am I ignoring Jurgensen and Thomason? In 1969, Vince Lombardi was Jurgensen’s coach with the Redskins, and if Lombardi invented the West Coast Offense I think we would have heard about it. … Continue reading

In 1956, Frankie Albert, the first quarterback in San Francisco history, became the team’s head coach. Albert starred at Stanford under Clark Shaughnessy, and was the first quarterback to play in the T-Formation. That gave him some experience with innovative offenses, as his Stanford team capped an undefeated season with a Rose Bowl win in 1940. One could argue that Albert created his own innovative offense with the ’49ers in the late ’50s.

In 1957, San Francisco finished 2nd in passing first downs (by two, to the Johnny Unitas Colts), and the 49ers finished first in completion percentage and last in yards per completion. San Francisco completed 62.6% of their passes, while the number two team in completion percentage, Baltimore, finished closer to league average than they did to the 49ers.

In 1958, the 49ers completed 58.2% of their passes, and again, the #2 team was closer to league average than to the 49ers. Again, the team finished last in yards per completion. And this year, the 49ers also finished first in passing first downs. In ’57, Tittle was the team’s main quarterback, but he split time with Brodie in 1958. That season, Brodie and Tittle finished first and second in completion percentage, Brodie finished last in yards per completion, and Tittle was just a hair behind Norm Van Brocklin for second to last in yards per completion. This is pretty strong evidence that the 49ers were running a West Coast Offense style of system, and it wasn’t just the quarterback.

Wide receiver Billy Wilson led the NFL in receptions in each of Albert’s first two seasons as head coach. From ’57 to ’58, he ranked last among the 11 receivers with at least 1,000 yards in yards per reception. The other receiver, Clyde Conner, caught 49 passes for only 512 yards in 1958. Hugh McElhenny played the Roger Craig role, and he rushed for 929 yards and gained 824 receiving yards combined in ’57 and ’58.

Unfortunately, that’s all I know about the ’57 and ’58 49ers. I don’t know much about Albert’s coaching philosophy, or have any extra knowledge about the system that produce those numbers for Tittle and Brodie. I’d love to hear from anyone who knows more about those San Francisco teams.

Saying that the West Coast Offense was all about throwing lots of short passes would be to a good way to demonstrate that one has a very shallow understanding of the West Coast Offense. There’s nothing particularly innovative about throwing a bunch of short passes instead of alternating between runs and long throws. But based on the statistics available, I get the sense that Albert was using some of the same basic principles that Walsh implemented a couple of decades later. I’d be curious to read anything about the type of offense Albert ran as a head coach, and how that compares to the West Coast Offense. Please leave your thoughts in the comments.

References

| ↑1 | Why am I ignoring Jurgensen and Thomason? In 1969, Vince Lombardi was Jurgensen’s coach with the Redskins, and if Lombardi invented the West Coast Offense I think we would have heard about it. As for Thomason, he split time that year with Tobin Rote, who had a very low completion percentage and a very high yards per completion average. That leads me to believe that Thomason’s numbers are a reflection of him, and not the offensive philosophy. |

|---|