The NFL Draft has emerged from an afterthought to the center of the sports world every April spring. A cottage industry of draftniks has emerged. Teams spend more time, money, and other resources on scouting than ever before. Scouting departments have grown exponentially in both size and sophistication. The Draft used to be much less important, as evidenced by the way teams happily traded away future first round picks like they were fringe benefits. Over the last 45 years, teams should have become a lot better at drafting. But have they?

Measuring how well teams draft in the aggregate is not easy. But suppose teams were perfect at drafting. In that case, the first pick would always turn out to be better than the second pick, the second pick would always turn out to be better than the third pick, and so on. Right?

Well, maybe not. Nobody quite knows the ratio, but player development is a crucial part of the drafting process. Prospects do not come to the NFL as finished products, and it’s up to the team (and the player) to turn that college athlete into an NFL player. Making a selection on draft day is just step one, not the final step. When a player busts, is it the fault or the person in charge of the draft or the person in charge of the development? When a player booms, is it because of the GM or the coach? I don’t know. You don’t know. Nobody knows.

But we do know that player development is an important variable, so even in a perfect drafting world, we probably wouldn’t expect each player to turn out to have a better career than the player drafted after him. But comparing draft status to player production seems like the most basic and obvious way to measure draft efficiency. Frankly, I don’t know even how else one would measure draft efficiency than by comparing draft slot to player production. I’m open to other ideas in the comments, but here’s what I did.

The top 25 selections

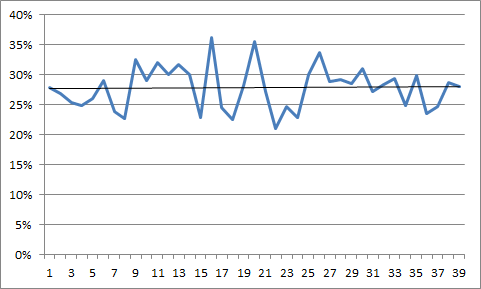

I looked at every draft from 1970 to 2008, and initially focused on the first 25 picks. [1]Why 25? If I used top 32, I was concerned I might bias the results by giving extra weight to bad teams with multiple picks in earlier years. Based on my Draft Value Chart, roughly 35% of all the draft value of the top 222 [2]Why 222? The 1994 Draft had just 222 picks. As we’ll see in a minute, I also analyzed the entire production from each draft, but limited myself to just the top 222 picks in each draft so as … Continue reading picks in every draft is captured in just the first 25 selections. Have teams become more efficient when it comes to the top 25 picks? The graph below shows the percentage of Career Approximate Value grades from Pro-Football-Reference.com for the top 25 picks (as a percentage of the total career AV of the top 222 picks) in each year from 1970 to 2008:

As you can see from that black trend line, teams aren’t extracting more value on a relative basis from the top 25 picks. In other words, there are still a lot of busts inside the top 25. That’s not a shocking conclusion to anyone, of course, but why haven’t teams improved when it comes to drafting first round picks over the last four decades? In 1978, the Bills traded an over-the-hill O.J. Simpson to San Francisco for the 49ers first round pick in 1979. That turned out to be the number one pick in the draft, which the Bills used on Tom Cousineau… who promptly went to Canada over Buffalo. That seems more like the leather helmet era than something approximating the modern NFL.

So shouldn’t teams be performing better? Shouldn’t there be fewer busts in the first round?

Making the matter more complicated, one could argue that better scouting could make it even harder to evaluate the draft. Maybe a Jimmy Graham — a basketball player who caught 17 passes in college — wouldn’t have been drafted 20 years ago, but in the modern era became a third round pick. So it’s a credit to scouting that a player like Graham was taken. As a result, if teams are finding more steals later in the draft, that would make the players selected in the first round look less valuable on a relative basis, which could explain what we see in this chart.

On the other hand, Graham looks to be one of the five or ten best players from the 2010 draft, so it’s easy to say that he’s an example of draft error. I mean, in retrospect, he would be a top ten pick, so should the NFL as a whole be punished or praised for Graham going at 95? That’s hard to say, and unfortunately, I have no answers. Four decades ago, it’s possible that Graham wouldn’t have even been drafted. But if teams are so good at finding steals now, what explains the myriad of first round disasters?

An alternative theory, and perhaps a desirable one, is that player development is more important than pure talent. A player’s work ethic should already be hard-wired into his draft status, so this would really be a reflection of each team. Can your wide receivers coach get the most out of the raw but talented rookie? Will your offensive line coach be able to improve on the technique of your 3rd round pick? On the other hand, teams don’t show a consistent ability to get more out of players than other teams, either.

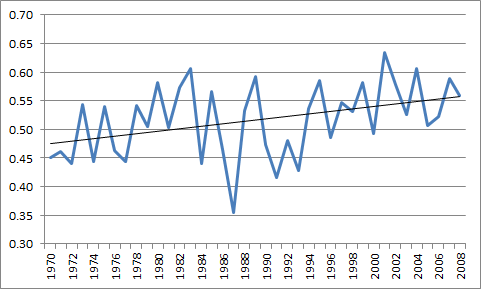

I looked at one other study that did seem to show some improvement by NFL teams. I measured the correlation coefficient between draft value and player production (using PFR’s AV) at the top 222 selections in each draft from 1970 to 2008. For draft value, I used the draft values from my draft pick calculator, calculated on a percentage basis of all 222 draft picks. For example, the 1st overall pick is worth 2.41% of all draft picks in each year, while the 53rd pick is worth 0.65%. For each player, his grade is a percentage of his Career AV divided by the total Career AV of the top 222 selections. So in 1970, Terry Bradshaw gets 2.41% of all draft pick value and 3.0% of all career AV; meanwhile, Mel Blount used only 0.65% of all draft capital but produced 2.9% of all career AV.

The correlation coefficient measures how closely the two variables are related. The results here are interesting: there is a moderately strong correlation (as we would expect) each year between draft value and career value. I then plotted the CC from each season over the period 1970 to 2008:

The black line shows that yes, drafting does appear to have gotten slightly better, at least since the early ’70s. But the early ’80s were a pretty efficient time for drafting, and the 2005 and 2006 drafts were not very “accurate” for our era. In ’05, Trent Cole, Frank Gore, Chris Myers, and Justin Tuck were later round picks who fared very well, while the end of the first round (Aaron Rodgers, Logan Mankins, Roddy White) were were better than many of the earlier picks (Troy Williamson, David Pollack, Mike Williams, Erasmus James, Cadillac Williams).

In 2006, Jahri Evans and Brandon Marshall were fourth round steals, Maurice Jones-Drew was a late second, and Kyle Williams, Cortland Finnegan, Charlie Johnson, Antoine Bethea, and Jeromey Clary were all successful end-of-draft selections. Meanwhile, Matt Leinart, Tye Hill, Vince Young, and Bobby Carpenter were first round picks who left a lot to be desired.

Perhaps the best question is how good can teams get at drafting? Are we already at the optimal level? That seems hard to believe, but I also can’t imagine that we’re ever going to get to a place where there are only a few busts in every first round. Let me know your thoughts in the comments, along with any other ideas on how to measure draft efficiency on a league-wide basis.

References

| ↑1 | Why 25? If I used top 32, I was concerned I might bias the results by giving extra weight to bad teams with multiple picks in earlier years. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Why 222? The 1994 Draft had just 222 picks. As we’ll see in a minute, I also analyzed the entire production from each draft, but limited myself to just the top 222 picks in each draft so as to compare apples to apples. |