On January 3, 2019, the St. Louis Blues had the worst record in the NHL. But by the end of the year, the Blues had captured their first championship. There is no similar success story in NFL history, but I was curious: which Super Bowl champion had the worst record after X games, for all X?

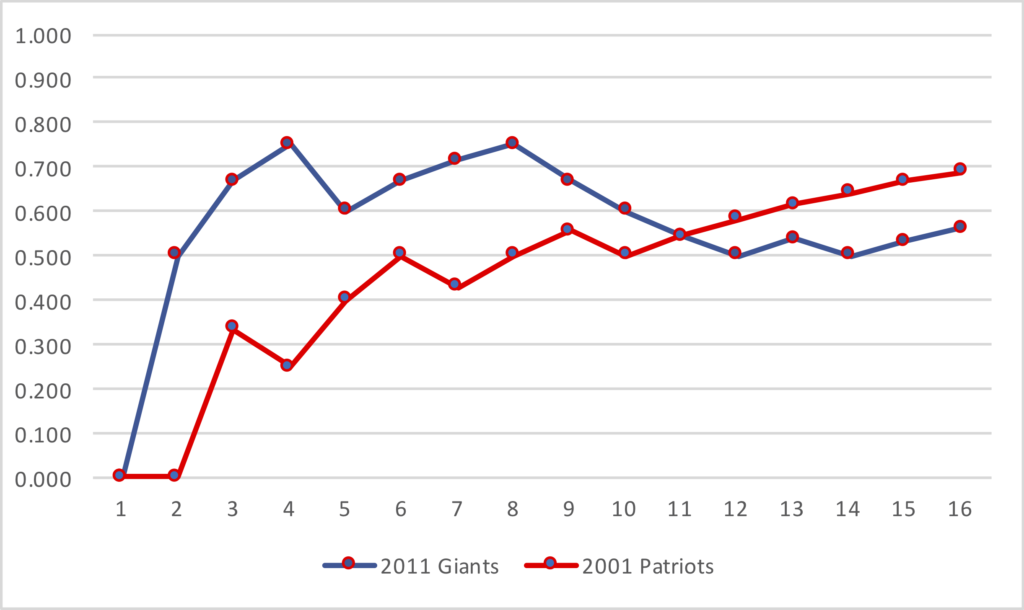

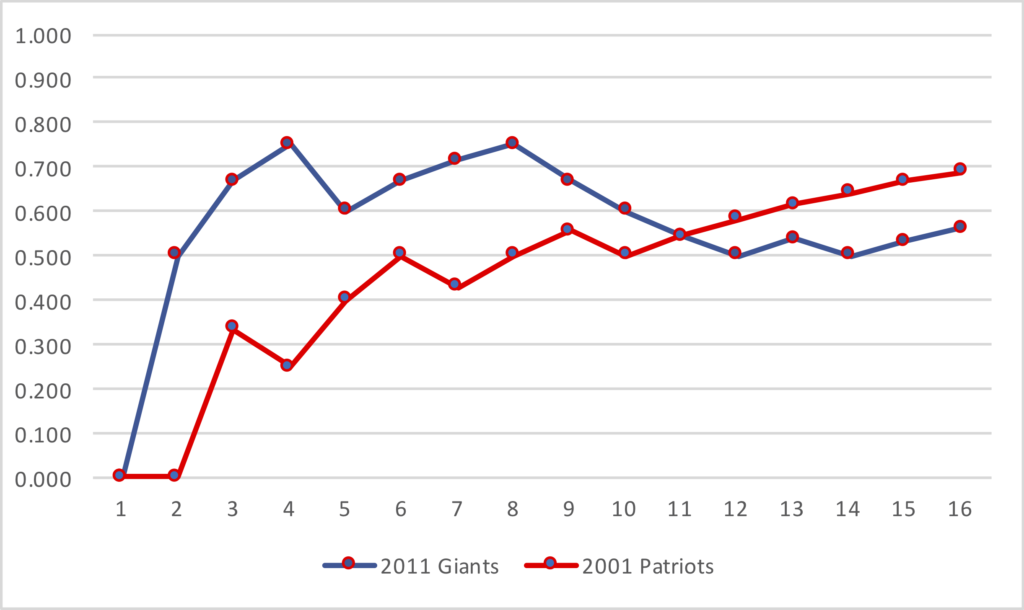

There have been 9 Super Bowl champions that began the year 0-1. That is not a very big hole from which to escape. But only three teams — the 1993 Cowboys, the 2001 Patriots, and the 2007 Giants — have won the Lombardi Trophy after an 0-2 start. And in the first two cases, it’s noteworthy that Emmitt Smith and Tom Brady were not part of that 0-2 start, but entered the starting lineup in week 3.

What about the worst team after 3 games to win a Super Bowl? 5 teams have begun the season with a 1-2 mark; the three teams mentioned above, along with the 1981 49ers and the 2018 Patriots.

After 4 games? Just one team has started 1-3 and won the Super Bowl: the 2001 Patriots.

After 5 games? Two teams have started 2-3 and won the Super Bowl: the 2001 Patriots and the 1980 Raiders.

After 6 games? No team has been 2-4, with the ’01 Patriots, ’80 Raiders, and the 2010 Packers.

After 7 games? Only team, the 2001 Patriots, had a losing record at 3-4 after 7 games.

After 8 games? Only the 2001 Patriots were 4-4 after 8 games; the other 52 Super Bowl champions had a winning record at this point in the season.

After 9 games? No team had a losing record and won the Super Bowl; in addition to the ’01 Patriots, the ’00 Ravens were the only other team at 5-4 after 9 games that won it all in the Super Bowl era (the ’57 Lions also pulled off this feat).

After 10 games? Yes, once again, we have a field of one: the 2001 Patriots are the only team without a winning record after 10 games, as New England began this season 0-2, 1-3, 3-4, and 5-5. That was the team’s last loss of the season.

After 11 games? Three teams started 6-5: the ’88 49ers, ’01 Patriots, and a new entry: the ’11 Giants.

After 12 games? Just one Super Bowl champion, the 2011 Giants, failed to have a winning record at this point in the season.

After 13 games? The 2011 Giants, at 7-6, are the lone entry here.

After 14 games? The 2011 Giants were 7-7! Only one other team, the 2010 Packers at 8-6, had even 6 losses after 14 games.

The 2011 Giants were the only team to win the Super Bowl with 7 losses, so they are the Super Bowl champion with the worst record after 15 and 16 games, too.

So the Patriots had the single worst record, either alone or tied with other teams, of any Super Bowl champion through X games, for all values of X from 1 to 11. At 6-5, the 2011 Giants were tied with the Patriots (and ’88 49ers) for worst record, and the 2011 Giants hold the mark for worst record of any Super Bowl champion through X games, for all values of X from 11 to 16. The graph below shows the winning percentages of both teams after each game of the regular season.

What do you think?