Neil Paine showed some interesting evidence relating to this idea on Friday. Looking at team performance since 2009 for teams with new quarterbacks, Neil showed that preseason passing efficiency helps predict regular season passing efficiency. It’s important to note that part of this result may have been pretty predictable even before we watched those preseason games. The 2012 Redskins replaced Rex Grossman and John Beck with the #2 pick in the draft who would have been #1 in an average year. So we would expect a big improvement to come just by way of moving from Grossman to a healthy RGIII. [continue reading…]

A couple of years ago, I asked how long it should have taken the Jaguars to move on from Blaine Gabbert. Today I want to revisit that general idea, but look at how long it takes the best quarterbacks to identify themselves as top-tier players. A couple of months ago, I looked at the greatest quarterbacks of all time. Using the top 75 quarterbacks from that list, I removed any player whose career began before the merger; that left me with 42 passers.

First, I looked at how each quarterback fared in relative Adjusted Net Yards per Attempt — i.e., ANY/A relative to league average — through their first 16 starts. Just over two-thirds of these passers were above average during their first 16 starts, with 1/3 of those quarterbacks being at least 1 ANY/A better than league average. That group of fourteen quarterbacks — which Aaron Rodgers just falls shy of joining — can be categorized as above-average quarterbacks from the beginning. They are Kurt Warner, Dan Marino, Daunte Culpepper, Chad Pennington, Tony Romo, Mark Rypien, Jeff Garcia, Boomer Esiason, Ben Roethlisberger, Philip Rivers, Matt Ryan, Joe Montana, Steve McNair, and Ken Stabler. Obviously a number of those quarterbacks were not immediate starters in the NFL, but they did excel as soon as they became starters.

The graph below shows each of the 42 quarterbacks’ Relative ANY/A through their first 16 starts. The X-Axis represents the quarterback’s first year, and the Y-Axis shows their RANY/A value through 16 starts.

Now, let’s remove the 14 quarterbacks who had a RANY/A of at least +1.0 through their first sixteen starts. How did the other 28 quarterbacks fare in starts 17 through 32 in RANY/A? Eleven of them produced a RANY/A of at least +1.0 in their next sixteen starts: Bert Jones, Matt Schaub, Ken Anderson, Peyton Manning, Aaron Rodgers, Brad Johnson, Carson Palmer, Jim Everett, Steve Young, Dan Fouts, and Steve Grogan.

Some teams, like the Rams have done a good job of fielding a very young roster; others, like the Raiders, have made a conscious effort to head in the other direction. Overall, the Rams are more representative of the current trend. NFL teams have made a shift towards younger players in the last three years, although you might be surprised by just how dramatic and sudden the change has been. The drop in Approximate Value (AV)-weighted ages of NFL rosters in the last three years is more than 50% larger than in any other three-year period in NFL history.

Looking at the graph, there are two seismic shifts that changed the age distribution of the NFL in the Super Bowl era: the increase that started in the late ‘80s and the decrease in the last five years. These changes tell us about how changes in the collective bargaining agreement can change the NFL landscape in both subtle and dramatic ways.

First, the increase in NFL roster age in the 1980s coincides pretty closely with the introduction of Plan B free agency in 1989. It looks like the increase maybe starts a year too early. Remember, though, that the 1987 age may be skewed a bit by the three games with replacement players. Taking that point in mind, the increase from 1988 through 1993 coincides exactly with the introduction of limited free agency. [continue reading…]

In the Super Bowl era, there has been just one team that was both the youngest in the league and one of the five best teams in football: the 2012 Seattle Seahawks. As friend of Football Perspective Neil Paine recently pointed out, being young and great has historically been a good predictor of teams that have become dynasties. Consider the table below. It captures every team since 1966 that ranked amongst the five youngest teams by Approximate Value (AV)-weighted age and had at least 12 Pythagenpat wins, adjusting everything to a 16-game schedule. [1]My AV-weighted age calculations are very similar to Chase’s, but not always exactly the same. For example, I have Seattle third in 2013, while he has them second. We both had Seattle at 26 years, … Continue reading

| Team | Year | Pyth Wins | AV-wtd age | Age Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIT | 1972 | 13.5 | 25.6 | 5 |

| DAL | 1992 | 12.6 | 26.4 | 2 |

| DAL | 1993 | 12.4 | 26.7 | 4 |

| STL | 1999 | 14.2 | 26.6 | 5 |

| CHI | 2001 | 12.4 | 26.5 | 5 |

| SDG | 2006 | 12.6 | 26.5 | 5 |

| IND | 2007 | 12.8 | 26.7 | 4 |

| SEA | 2012 | 12.6 | 25.8 | 1 |

| SEA | 2013 | 13.1 | 26 | 3 |

There are seven unique teams on this list, not counting the two repeaters. When trying to predict what’s going to happen with the Seahawks, there are two different ways to look at this list. The first looks good for their dynasty potential. The first two teams on the list, the ’72 Steelers and the ’92 Cowboys went on to win multiple Super Bowls. The closest comparison in terms of age also looks pretty good. Teams used to be younger, so the best comparison probably isn’t the ’72 Steelers, who were even younger by age but were only the fifth-youngest team in 1972, but the ’92-’93 Cowboys. They are the only other team on this list to be so young and so good.

Of course, even the Cowboys had a pretty short run. Their stay at the top was nothing like the ’70s Steelers or ’80s Niners, who were also quite young. [2]They were the third-youngest team in 1981, their first championship year. Free agency helped to minimize their time on top. The ’90s Cowboys were the first great team in the free agency era. Players gained full freedom of movement only in the year after their first Super Bowl. Plan B free agency allowed limited movement starting in 1989.

Free agency and the salary cap help to explain the path of the other four teams on the list. They point towards a more cautious prediction about the Seahawks’ dynasty hopes. Between them, the ’99 Rams, ’01 Bears, ’06 Chargers, and ’07 Colts won one Super Bowl and played in two others. Within three years of their great-and-young season, only the Chargers were significantly better than league-average.

These more recent examples may do a better job of predicting the Seahawks future success. Before the beginning of full free agency in 1993, good-and-relatively-young teams appear to have generally followed a clear and sustained upwards trajectory over the long term. Since then, however, success has generally been less sustainable. The table below looks at teams’ strengths over time according to PFR’s Simple Rating System. [3]I thank Bryan Frye for sharing his SRS dataset. Here I’ve made the cutoff any team that was in the five youngest teams in a given year and also had a SRS rating of at least 6. The table shows the trend in strength for the previous season and the following three seasons.

| Team | Year | SRS (t-1) | SRS (t) | SRS (t+1) | SRS (t+2) | SRS Wins (t+3) | AV-wtd age | Age Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIT | 1972 | -3.6 | 10 | 8.2 | 6.8 | 14.2 | 25.6 | 5 |

| BAL | 1975 | -8.7 | 8.6 | 9.8 | 5 | -8.8 | 25.9 | 5 |

| SFO | 1981 | -6.2 | 6.2 | -2.4 | 8.7 | 12.7 | 25.8 | 3 |

| NOR | 1987 | 0 | 10.1 | 1.5 | 4.6 | -1.3 | 26 | 4 |

| DAL | 1992 | 4.4 | 9.9 | 9.6 | 10.1 | 9.7 | 26.4 | 2 |

| Average | -2.82 | 8.96 | 5.34 | 7.04 | 5.3 | 25.94 | 3.8 |

| Team | Year | SRS (t-1) | SRS (t) | SRS (t+1) | SRS (t+2) | SRS (t+3) | AV-wtd age | Age Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAL | 1993 | 9.9 | 9.6 | 10.1 | 9.7 | 2.4 | 26.7 | 4 |

| IND | 1999 | -5.4 | 6.1 | 7.9 | -3.8 | 1.2 | 25.6 | 1 |

| STL | 1999 | -2.3 | 11.9 | 3.1 | 13.4 | -3.3 | 26.6 | 5 |

| IND | 2000 | 6.1 | 7.9 | -3.8 | 1.2 | 7 | 26.3 | 3 |

| CHI | 2001 | -6.3 | 7.9 | -5.3 | -3.5 | -8.2 | 26.5 | 5 |

| BAL | 2003 | -2.1 | 6.3 | 6.1 | -1.8 | 9.3 | 26.4 | 3 |

| IND | 2003 | 1.2 | 7 | 11.4 | 10.8 | 5.9 | 26.5 | 4 |

| SDG | 2004 | -6.8 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 26.5 | 2 |

| BAL | 2004 | 6.3 | 6.1 | -1.8 | 9.3 | -6.7 | 26.7 | 3 |

| SDG | 2005 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 5 | 26.8 | 5 |

| JAX | 2006 | 4.8 | 7.5 | 6.8 | -2.5 | -6.5 | 26.5 | 2 |

| SDG | 2006 | 9.9 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 5 | 6.6 | 26.5 | 5 |

| SDG | 2007 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 5 | 6.6 | 4.8 | 26.4 | 2 |

| IND | 2007 | 5.9 | 12 | 6.5 | 5.9 | 2.9 | 26.7 | 4 |

| SEA | 2012 | 0.8 | 12.2 | 13 | 25.8 | 1 | ||

| SEA | 2013 | 12.2 | 13 | 26 | 3 | |||

| Average | 3.34 | 9.09 | 5.86 | 4.95 | 2.09 | 26.41 | 3.25 |

One surprising pattern in these data is just how infrequently young teams won in the past. From 1966-1992, only five teams were among the five youngest and still had an SRS of at least 6. Since 1993, it’s happened 16 times. In the past, teams had more of an opportunity to gradually build strength. So it looks like there was a greater share of young teams building for something and old teams trying to stay on top. Since 1993, the standard deviation of team ages is about 20% smaller than it was before that. In the last ten years, the standard deviation is about 30% smaller than it was before 1993. The ages of rosters are more compressed than they used to be.

The other thing to take away from these tables is the dropoff in years 2 and 3 since full free agency. For the pre-1993 teams, the good-and-young teams held much of their value. After starting at an average SRS of 8.96, they were still at 7.04 two years later and then 5.3 three years later. Since 1993, teams have deteriorated more quickly. From an average of 9.09, the more recent high quality young teams fell to 4.95 two years later and all the way to 2.09 three years later.

Since there are only five teams in the pre-1993 group, we want to be careful with interpreting too much into the earlier data. It’s possible that the ’72 Steelers and ’81 Niners are anomalies. At the same time, the success three years later is skewed downwards by the ’75 Colts, who would have been much stronger in ’78 if they had a healthy Bert Jones.

With the bigger set of more recent teams, the clear takeaway is that in the current era, even very good and young teams are just slightly better than average than three years later. The Seahawks may buck this trend, but they probably won’t. With Russell Wilson to sign and long-term cap hits for players like Richard Sherman and Earl Thomas, they’re more likely to have a brief run than a long one.

Another alternative may be available, though. If Wilson makes the leap into the Brady-Manning class (he may) and Pete Carroll turns out to be a truly elite coach (also possible), they may be able to fashion a New England-kind of dynasty. That sort of dynasty is not really built on youth. Consider the aging patterns of the last five teams of the decade.

The ‘60s Packers, ‘70s Steelers, ’80s Niners, ‘90s Cowboys all showed the same pattern of being relatively young and then progressively aging during their runs. On the other hand, the Patriots show an entirely different pattern. They’re the only dynasty to actually not age as their run progressed. They started old and stayed old through their Super Bowl years. While the Seahawks are starting off younger than those Patriots teams, excellence at QB and coach still offers them their best hope of building a dynasty in the current NFL. The benefits of being young and good are much more fleeting than they used to be.

References

| ↑1 | My AV-weighted age calculations are very similar to Chase’s, but not always exactly the same. For example, I have Seattle third in 2013, while he has them second. We both had Seattle at 26 years, but I have Cleveland also at 26, instead of 26.1. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | They were the third-youngest team in 1981, their first championship year. |

| ↑3 | I thank Bryan Frye for sharing his SRS dataset. |

The past couple of days, we looked at the players with the most receiving yards and rushing yards in their final 16 regular season games. Today, we get to the quarterbacks.

Only one non-active player threw for 4,000 yards in his final 16 games.

| Trivia hint | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

Three other players threw for 3900+ yards. That doesn’t include Dan Fouts (3,805) or Dan Marino (3,869), but it does include quarterbacks from the great, the good, and the ugly category.

| Trivia hint 1 | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint 2 | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint 1 | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint 2 | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint 1 | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint 2 | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

I’m still short on time, so let’s keep the trivia train rolling. Yesterday, I looked at the players with the most receiving yards in their last 16 regular season games. Today, the players with the most rushing yards in their last 16 games.

Excluding LeSean McCoy, Adrian Peterson, and Doug Martin, only five players have rushed for over 1,500 yards in their final sixteen games. The record-holder rushed for 1,702 yards in his final sixteen games. Do you know who it is?

| Trivia hint | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

One other player rushed for at least 1,600 yards in his last 16 games Can you name him?

| Trivia hint | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

What about the other three players who rushed for 1,500 yards in their careers? All three retired early.

| Trivia hint | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

I’m very short on time this week, so here’s a fun trivia question. Last week, I noted that Justin Blackmon gained 1,201 receiving yards in his last 16 games. As it turns out, if Blackmon never plays in another NFL game, that would set the record for most receiving yards in a player’s final sixteen games (this excludes all active players, of course).

Who holds that record now? Two players gained just over 1,100 yards in their final sixteen games. Can you name them?

| Trivia hint 1 | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint 2 | Show |

|---|---|

| Trivia hint 3 | Show |

|---|---|

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

Rounding out the top five: Hart Lee Dykes caught 71 passes for 1,098 yards in his final sixteen games, as an off-the-field incident (which has nothing on this off-the-field incident) and repeated knee injuries ended his career. Finally, Terrell Owens gained 80 receptions, 1,087 yards, and 10 touchdowns in his last sixteen games.

September 23rd, 1981

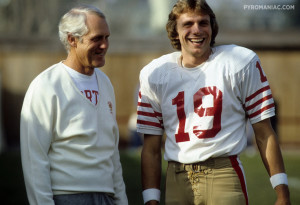

I’m not here to tell you that Bill Walsh is a bad coach. And I’m not here to tell you that Joe Montana can’t possibly succeed in the NFL. It’s just that if they want to still be here in two years, some changes are in order.

Walsh comes from the great Paul Brown coaching tree, and like his mentor, Walsh likes to throw the ball. That strategy, while unconventional, can work well when you have a Hall of Famer like Otto Graham or even a great talent like Ken Anderson. It doesn’t work when you have a scrappy young player like Montana. And lest you forget, Brown never won anything without Graham, and Brown’s Bengals went 55-56-1 with zero playoff wins.

Undeterred by that evidence, Walsh went about bringing Basketball On Cleats to Candlestick Park. Was his first year a success? San Francisco finished third in passing yards, 4th in first downs, and 6th in total yards. Quarterback Steve DeBerg led the NFC in completion percentage, too. But while Walsh’s horizontal passing game led to lots of yards and first downs, the team won only two games. Running backs Paul Hofer and Wilbur Jackson each caught 50 passes, but to what end?

They were two of only nine running backs to hit the 50-catch plateau in 1979, but what good is it passing to your running backs when you can’t attack a defense vertically? In a telling statistic, Baltimore was the only other team to have two running backs catch 50 passes, and the Colts went 5-11. The 49ers ranked 3rd from the bottom in rush attempts that season, but were above average in yards per carry. Maybe somebody should tell The Genius that San Francisco could have benefited from more runs and fewer passes.

The man who thinks he’s the smartest person in every room surely was going to learn from his 1979 failures, right? In 1980, Montana was handed the reins. How did he do? Walsh continued with his horizontal offense: Montana completed 64.5% of his passes, the 4th highest by a quarterback in NFL history (behind the great Ken Stabler and two Brown robots, Anderson and Graham). But the team went just 2-5 in Montana’s starts.

Fullback Earl Cooper was a nice player at Rice, but he was drastically overused by the 49ers last season. In addition to a team-high 171 carries, he caught 83 passes — but for only 567 yards. Cooper became the first player in NFL history to catch 80 balls and not get 700 yards, much less 567 yards. Cooper averaged an anemic 6.8 yards per reception, and prior to last year, no player with fewer than seven yards per catch had come within 20 passes of Cooper’s 83 grabs. In other words, the 49ers relied more heavily on a player doing so little more than any team in NFL history. Sure, the 49ers ranked 5th in passing yards, but they ran just 415 times, the second fewest number in the league. The team led the NFL in pass attempts and went 6-10 with an eight-game losing streak in the middle of the season. Genius. [continue reading…]

In 2013, the average completion went for 11.63 yards. That’s a pretty low number historically, although it’s actually a bit higher than some of the recent NFL seasons. Take a look at how Yards per Completion has generally been declining throughout NFL history:

If you want to discuss the quarterbacks who excelled in this metric, controlling for era is crucial. One simple way to measure the best passers when it comes to YPC is to measure how they fare in this metric relative to league average, and multiply that difference by the player’s number of attempts. For example, Nick Foles averaged 14.2 YPC last year, which was 2.6 YPC above average. Over the course of his 317 pass attempts, we could say he provided 529 yards above the average completion. That was the highest in the NFL last year, while Matt Ryan produced the lowest average. [continue reading…]

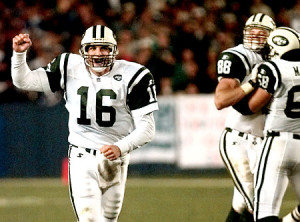

The 1998 season was one of my favorite years in NFL history. It was also a pretty weird one. We had Terrell Davis rushing for 2,000 yards, rookies Randy Moss and Fred Taylor making defenses look silly, and a quartet of old quarterbacks stun the football world. Doug Flutie came out of nowhere Canada to lead the Bills to a 7-3 record after being out of the NFL for nine years. Randall Cunningham, who had retired after the ’96 season, came off the bench in ’98 to produce one of the best backup seasons in NFL history. The other two quarterbacks are the stars of this post.

Vinny Testaverde had a very up-and-down career, although he was almost certainly a much better quarterback than you remember. Okay, Testaverde has lost more games than any other quarterback, but he played on some really bad teams throughout his career. Testaverde retired with a career winning percentage of 0.423. In 1998, he started 13 games for the Jets; based on that career winning percentage, we would have expected him to win 5.5 games in 1998. Instead, Testaverde went 12-1 in the regular season, giving him 6.5 more wins than we would expect. If that sounds remarkable to you, it should: that’s the 2nd largest discrepancy of any quarterback in NFL history in a single season (minimum 40 career wins). [continue reading…]

In 2000, a second-year Akili Smith was given the starting job and posted a miserable 52.8 passer rating. A year later, Jon Kitna took over for the Bengals, and his 61.1 rating was the worst among qualifying passers.

In 1993, Mark Rypien finished with the worst passer rating in the league two years after winning the Super Bowl. Washington drafted Heath Shuler the following year, and as a rookie, Shuler finished with the worst passer rating in the NFL.

The Seahawks almost pulled off this feat in the prior two years. In 1992, Stan Gelbaugh had the worst passer rating as part of the historically inept Seattle passing attack. In 1991, Jeff Kemp finished with the worst passer rating in the league. Kemp, the son of Jack , started the year with Seattle but finished it with Philadelphia. He didn’t have enough attempts with the Seahawks to qualify, so I probably wouldn’t include the ’91-’92 Seahawks in this category, although that may be pickin’ nits.

The table below shows the quarterbacks to finish with the lowest passer rating in the NFL in each year since the merger. For each passer, I’ve included his age as of September 1st of that season, his traditional metrics, and his passer rating. [continue reading…]

Mendenhall ended the season with 687 yards on 217 yards, a 3.2 yards per carry average. Ellington finished his rookie year with 118 carries for 652 yards, producing 5.5 yards per rush. One way to measure the magnitude of the difference in the effectiveness of these two players — and boy was there a large difference — is to simply look at the delta in the players’ yards per carry averages. In this case, that’s 2.36 yards per carry.

Where does that rank historically? Some teams — I’m looking at the Lions in the early Barry Sanders years — gave only a handful of carries to their backup running backs. So one thing we can do is to take the difference in the yards per carry between the team’s top two running backs and multiply that number by the number of carries by the running back with the lower number of carries. In each instance, I’ve defined the running back with the most carries as the team’s RB1, and the running back with the second most carries as the RB2. In Arizona’s case, that would mean multiplying -2.36 (Mendenhall’s average, since he was the RB1, minus Ellington’s average) by 118, the number of carries Ellington recorded. That produces a value of -278. [continue reading…]

Yesterday, I looked at the best AV-weighted winning percentages of offensive players. Today, we examine the same numbers but for defensive players and kickers since 1960. Again, players who entered the league prior to 1960 are included, but for purposes of this study, only their 1960+ seasons count (assuming they produced at least 50 points of AV). That’s a pretty important bit of detail to mention when it comes to the top player on the list. The player with the best AV-adjusted winning percentage since 1960 is Packers linebacker Bill Forester, who entered the NFL in 1953 but only gets credit for his 1960-1963 seasons in Green Bay (spoiler: those were pretty good ones). After him, of course, we have yet another Patriots lineman. Today it’s Vince Wilfork: [continue reading…]

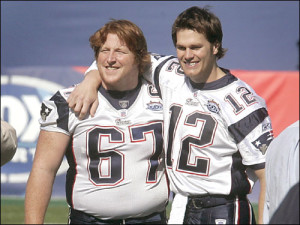

By this methodology, Dan Koppen has the highest AV-weighted career winning percentage of any offensive player since 1960. The table below shows his AV and team’s winning percentage in each season of his career. Because Koppen’s best season came in 2007, when the Patriots went 16-0, Koppen’s career winning percentage gets a big boost from that season (18.7% of his career winning percentage comes from ’07 since 18.7% of his career AV comes from that year). On the other hand, Koppen played in just one total game for the 13-3 Patriots (2011) and the 13-3 Broncos (2013), so he gets almost no credit for those performances. Of course, he doesn’t need it, because his average season, after adjusting the weights based on his AV grades, was a 13-3 season.

| Year | Tm | G | GS | AV | Record | % of Car AV | WtWin% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | NWE | 16 | 15 | 7 | 0.875 | 8% | 0.07 |

| 2004 | NWE | 16 | 16 | 10 | 0.875 | 11.5% | 0.101 |

| 2005 | NWE | 9 | 9 | 5 | 0.625 | 5.7% | 0.036 |

| 2006 | NWE | 16 | 16 | 10 | 0.75 | 11.5% | 0.086 |

| 2007 | NWE | 15 | 15 | 16 | 1 | 18.4% | 0.184 |

| 2008 | NWE | 16 | 16 | 10 | 0.688 | 11.5% | 0.079 |

| 2009 | NWE | 16 | 16 | 10 | 0.625 | 11.5% | 0.072 |

| 2010 | NWE | 16 | 16 | 11 | 0.875 | 12.6% | 0.111 |

| 2011 | NWE | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.813 | 1.1% | 0.009 |

| 2012 | DEN | 15 | 12 | 7 | 0.813 | 8% | 0.065 |

| 2013 | DEN | 0 | 0 | 0.813 | 0% | 0 | |

| Total | 0 | 100% | 0.813 |

The table below shows the top 500 career AV-adjusted winning percentages among all offensive player since 1960 (minimum: 50 points of AV). As always, players who entered the NFL before 1960 are included but only their seasons beginning in 1960 count. The table below is fully sortable and searchable, so get to searching and leave your thoughts in the comments. [continue reading…]

Okay, some fun trivia to kick off the week. Do you know which team last year had the worst points differential in games they lost? I’ll put the answer in spoiler tags.

| Click 'Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

Where does that rank historically? I thought it would be fun to look at the teams since 1950 with the worst average margin of defeat looking exclusively at performance in losses. This was a bit of a tricky one, but Scott Kacsmar was able to guess it on twitter. The answer?

| Show' for the Answer | Show |

|---|---|

The table below shows the 100 teams with the worst average points differential in losses since 1950. As always, the tables in this post are fully sortable and searchable. For viewing purposes, I’m displaying only the top 20, but you can change that in the dropdown box on the left. [continue reading…]

Yesterday, we looked at the Billick Index, a measure of coaches who managed teams that were good at preventing offensive touchdowns and bad at creating them. Today, the reverse, which is appropriately named after Don Coryell. Coryell’s teams were slanted towards the offense even when he was in St. Louis, but the situation exploded when he went to San Diego. Here’s a look at Coryell’s year-by-year grades in the Coryell Index: for example, in 1981, his Chargers scored 23.1 more offensive touchdowns than the average team, while opposing offenses against San Diego scored 10.1 more touchdowns than average. Add those two numbers together, and there were 33.3 more offensive touchdowns scored in San Diego games than in the average game in 1981 (this is the same information presented as yesterday, but now the “Grade” column reflects the number above average).

| Year | Record | OFF | DEF | GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | 4-9-1 | 1.8 | -11.8 | 13.5 |

| 1974 | 10-4 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 1 |

| 1975 | 11-3 | 6.5 | 0.5 | 5.9 |

| 1976 | 10-4 | 4.8 | -1.8 | 6.6 |

| 1977 | 7-7 | 6.6 | -6.6 | 13.1 |

| 1978 | 8-4 | 6.8 | -1.6 | 8.4 |

| 1979 | 12-4 | 12.4 | 6.6 | 5.8 |

| 1980 | 11-5 | 11 | 1 | 9.9 |

| 1981 | 10-6 | 23.1 | -10.1 | 33.3 |

| 1982 | 6-3 | 14.3 | -0.3 | 14.6 |

| 1983 | 6-10 | 5.1 | -16.1 | 21.1 |

| 1984 | 7-9 | 6.4 | -13.4 | 19.8 |

| 1985 | 8-8 | 19.8 | -15.8 | 35.6 |

| 1986 | 1-7 | 2.4 | -2.9 | 5.3 |

| Total | 111-83-1 | 124.4 | -69.6 | 194 |

The 2004 Ravens were hardly Brian Billick’s most interesting team. But those Ravens serve as a shining example of what you envision when you think of Baltimore in the 2000s: terrible on offense and great on defense. The team went 9-7 despite the Kyle Boller-led offense producing just 24 touchdowns, tied for the second fewest in the league. But Ray Lewis, Ed Reed, Terrell Suggs, Chris McAlister, and even Deion Sanders were on a defense that allowed only 23 touchdowns, the second best mark in the NFL. So Baltimore was +1 in net offensive touchdowns, but that doesn’t really demonstrate the type of team the Ravens were.

Here’s a better way: the average team in 2004 produced 35.9 offensive touchdowns. This means the Baltimore offense fell 11.9 touchdowns shy of average, while the defense was 12.9 touchdowns above average. So if you don’t like watching offensive touchdowns, the 2004 Ravens were the team for you: 24.8 fewer offensive scores came in Ravens games than in the average game that season.

That’s the 4th largest negative differential in NFL history, behind…

- The 2002 Bucs (-25.1), who allowed 18.1 fewer touchdowns than average while scoring 7.1 fewer offensive touchdowns;

- The 2005 Bears (-26.2), who allowed 14.6 fewer offensive touchdowns to opponents, and produced 11.6 fewer offensive touchdowns than average; and

- The 1967 Oilers (-28.7), who allowed 17.3 fewer offensive touchdowns than average and scored 11.3 fewer offensive touchdowns than the rest of the AFL.

Economists (I am one) have historically been trained to believe in the efficiency of markets. The simplest way to think of this is that market prices capture all relevant information. Of course, this is sometimes not quite right, or even close to right. All the mortgage-backed securities that helped bring down our economy were horrendously mispriced, for example, despite lots of people seeing the warning signs. Even then, people betting against those securities provided information about their true value. They were just drowned out for too long by people clamoring to buy that worthless stuff.

The sports betting market, though, is a case that we might actually expect to work better. Unlike mortgage-backed securities, everyone making a wager in Las Vegas is incentivized to get the price right. There’s nobody who’s pushing a bad wager on their clients, for example. [1]These perverse incentives have been going on a long time, too. Check out Michael Lewis’s Liar’s Poker for fascinating stories of investment bankers pushing junk on their clients. Therefore, we might expect efficient markets to mostly work in Vegas and that the odds would converge to the correct number.

Mostly, it seems like that’s what’s going on. Whatever information is not contained in the initial odds may be quickly corrected as people swoop in to take advantage. I’ve experienced this first-hand. Last year, I went to Vegas about a week after the first season win-totals for 2013 came out. I found the numbers online and came up with this list of wagers I was interested in. [continue reading…]

References

| ↑1 | These perverse incentives have been going on a long time, too. Check out Michael Lewis’s Liar’s Poker for fascinating stories of investment bankers pushing junk on their clients. |

|---|

A few years ago, Mike Tanier wrote a great column on the 1986 Eagles, the team that obliterated the record for sacks allowed with 104. But since Philadelphia had 53 sacks of their own (having Reggie White tends to help), Philadelphia was able to pull into a tie for worst sack differential of all time. That honor of -51 is shared with the 1961 Minnesota Vikings, an expansion team led by our good pal Fran Tarkenton. Minnesota’s defense recorded an absurdly low 16 sacks that season (the 14-team league average, including Minnesota, was 38), and led the league by a substantial margin with 67 sacks, most of them attributed to Tarkenton. Back then, expansion teams were not very good, although the team would turn things around soon.

What about the teams with the best sack differential? Four teams have recorded 40 or more sacks than they’ve allowed. [continue reading…]

What I’ve historically done — and done here — is to give each quarterback 100% of his value or score from his best season, 95% of his score in his second best season, 90% of his score in his third best season, and so on. This rewards quarterbacks who played really well for a long time and doesn’t kill players with really poor rookie years or seasons late in their career. It also helps to prevent the quarterbacks who were compilers from dominating the top of the list. For visibility reasons, the table below displays only the top 25 quarterbacks initially, but you can change that number in the filter or click on the right arrow to see the remaining quarterbacks. [1]Note that while yesterday’s list was just from 1960 to 2013, the career list reflects every season in history, using the same methodology as used in GQBOAT IV.

Here’s how to read the table. Manning’s first year was in 1998, and his last in 2013. He’s had 8,740 “dropbacks” in his career, which include pass attempts, sacks, and rushing touchdowns. His career value — using the 100/95/90 formula [2]And including negative seasons. is 12,769, putting him at number one. His strength of schedule has been perfectly average over his career; as a reminder, the SOS column is shown just for reference, as SOS is already incorporated into these numbers (so while Tom Brady has had a schedule that’s 0.25 ANY/A tougher than average, that’s already incorporated into his 10,063 grade). Manning is not yet eligible for the Hall of Fame, of course, but I’ve listed the HOF status of each quarterback in the table. Note that I only have quarterback records going back to 1960; therefore, for quarterbacks who played before and during (or after) 1960, only their post-1960 record is displayed. In addition, SOS adjustments are only for the years beginning in 1960. [continue reading…]

In 2006, I took a stab at ranking every quarterback in NFL history. Two years later, I acquired more data and made enough improvements to merit publishing an updated and more accurate list of the best quarterbacks the league has ever seen. In 2009, I tweaked the formula again, and published a set of career rankings, along with a set of strength of schedule, era and weather adjustments, and finally career rankings which include those adjustments and playoff performances. And two years ago, I revised the formula and produced a new set of career rankings.

This time around, I’m not going to tweak the formula much (that’s for GQBOAT VI), but I do have one big change that I suspect will be well-received. Let’s review the methodology.

Methodology

We start with plain old yards per attempt. I then incorporate sack data by removing sack yards from the numerator and adding sacks to the denominator. [1]I have individual game sack data for every quarterback back to 2008. For seasons between 1969 and 2007, I have season sack data and team game sack data, so I was able to derive best-fit estimates for … Continue reading To include touchdowns and interceptions, I gave a quarterback 20 yards for each passing touchdown and subtracted 45 yards for each interception. This calculation — (Pass Yards + 20 * PTD – 45 * INT – Sack Yards Lost) / (Sacks + Pass Attempts) forms the basis for Adjusted Net Yards per Attempt, one of the key metrics I use to evaluate quarterbacks. For purposes of this study, I did some further tweaking. I’m including rushing touchdowns, because our goal is to measure quarterbacks as players. There’s no reason to separate rushing and passing touchdowns from a value standpoint, so all passing and rushing touchdowns are worth 20 yards and are calculated in the numerator of Adjusted Net Yards per Attempt. To be consistent, I also include rushing touchdowns in the denominator of the equation. This won’t change anything for most quarterbacks, but feels right to me. A touchdown is a touchdown.

Now, here comes the twist. In past year, I’ve compared each quarterback’s “ANY/A” — I put that term in quotes because what we’re really using is ANY/A with a rushing touchdowns modifier — and then calculated a value over average statistic after comparing that rate to the league average. For example, if a QB has an “ANY/A” of 7.0 and the NFL average “ANY/A” is 5.0, and the quarterback has 500 “dropbacks” — i.e., pass attempts plus sacks plus rushing touchdowns — then the quarterback gets credit for 1,000 yards above average. [continue reading…]

References

| ↑1 | I have individual game sack data for every quarterback back to 2008. For seasons between 1969 and 2007, I have season sack data and team game sack data, so I was able to derive best-fit estimates for each quarterback in each game. For seasons between 1960 and 1969, I gave each quarterback an approximate number of sacks, giving him the pro-rated portion of sacks allowed by the percentage of pass attempts he threw for the team. |

|---|

It’s fun to play with weighted averages to see how the NFL has (or hasn’t) evolved. For example, the Giants led the league with interceptions: as a result, 5.8% of all interceptions thrown in the NFL last year were by Eli Manning or Curtis Painter. Since the Giants went 7-9 in 2013, that means 5.8% of all interceptions were thrown by a team that had a 0.438 winning percentage. Meanwhile, Kansas City and San Francisco each threw just 8 interceptions, or 1.6% of all NFL interceptions, and the Chiefs and 49ers had an average winning percentage of 0.719.

So while the average winning percentage of all NFL teams is of course 0.500, the average weighted (by interceptions) winning percentage of all NFL teams will be below .500 because bad teams tend to throw more interceptions than good teams. Last year, the averaged weighted winning percentage was 0.464 for all NFL teams.

What’s interesting is how little variation there has been over the years in weighted winning percentage. In fact, it’s been between 45% and 50% in just about every year since 1950: [continue reading…]

This year, the Vikings will play their home games at the University of Minnesota’s TCF Bank Stadium. The Metrodome is no longer, and Minnesota will play outdoors for two years before moving into a new indoor facility in 2016.

Should we expect the Vikings to struggle in 2014 in their temporary home? This scare piece noted that since the merger, only four teams (excluding those that moved cities) have played games in a temporary stadium for at least one season, and those teams saw an average decline of 5.8 wins. That’s a pretty misleading statistic, though. Consider:

- One of the teams included was the 2005 Saints, who dropped from 8 to 3 wins as the team played “home” games in Baton Rouge, San Antonio, and uh, East Rutherford following Hurricane Katrina. I don’t think the 2005 Saints are an appropriate comparison for any team.

- Another team was the 2002 Chicago Bears, who played in Champaign, Illinois while Soldier Field was being remodeled. The 2001 Bears were one of football’s great flukes: Chicago’s win probability added in the 4th quarter and overtime of games was one of the highest ever. Jim Miller and Shane Matthews led five 4th quarter comebacks. The Bears were 27th in yards per carry, allowed more net yards per pass than they gained, and yet went 13-3. Safety Mike Brown scored interception return touchdowns in overtime in consecutive weeks. And then the Bears promptly went 4-12 in 2002.

- The 1973 Giants are another team used in the study. New York used to play in Yankee Stadium, which as you may know was primarily a baseball park. On September 30th, 1973, the stadium closed for renovations for two (baseball) years. Of course, that meant it would be closed for nearly three football years: the Giants played the rest of ’73 and all of 1974 at the Yale Bowl in Connecticut; in 1975, the Giants shared Shea Stadium with the Jets, just as the Yankees were doing with the Mets.

It is the soldier, not the reporter, who has given us freedom of the press. It is the soldier, not the poet, who has given us freedom of speech. It is the soldier, not the campus organizer, who has given us the freedom to demonstrate. It is the soldier, who salutes the flag, who serves beneath the flag, and whose coffin is draped by the flag, who allows the protester to burn the flag.

— Father Dennis Edward O’Brien, USMC

Today is a day that we as Americans honor and remember those who lost their lives protecting our country. As my friend Joe Bryant says, it’s easy for the true meaning of this day to get lost in the excitement of summer and barbecues and picnics. But that quote helps me remember that the things I enjoy today are only possible because those before me made incredibly selfless sacrifices. And since this is a football blog, I thought I’d take the time to remember the many football players who have lost their lives defending our country.

The most famous, of course, is Pat Tillman, the former Arizona Cardinals safety who chose to quit football to enlist in the United States army. On April 22, ten years ago, Tillman died in Afghanistan. In Vietnam, we lost both Bob Kalsu and Don Steinbrunner. You can read their stories here. Hall of Famers Roger Staubach, Ray Nitschke, and Charlie Joiner were three of the 28 NFL men to serve in the military during that war.

An incredible 226 men with NFL ties served in the Korean War, including men like Night Train Lane and Don Shula. But it was World War II that claimed the lives of 21 former NFL players.

I first encountered the list below from Sean Lahman, identifying those 21 players.

- Nick “Mike” Basca

- Charlie Behan

- Keith Birlem

- Al Blozis

- Chuck Braidwood

- Young Bussey

- Ed Doyle

- Grassy Hinton

- Smiley Johnson

- Eddie Kahn

- Alex Ketzko

- Lee Kizzire

- Jack Lummus

- Roy “Bob” Mackert

- Frank Maher

- Jim Mooney

- Gus Sonneberg

- Len Supulski

- Don Wemple

- Chet Wetterlund; and

- Waddy Young

Jack Chevigny, former coach of the Cardinals, and John O’Keefe, an executive with the Eagles, were also World War II casualties. The Pro Football Hall of Fame has chronicled the stories of these men, too. Lummus received the Medal of Honor for his bravery at Iwo Jima, and you can read more about his sacrifice here.

While today isn’t Veterans Day, I’d still like to close with some more words from Father Dennis Edward O’Brien.

What is a Veteran?

Some veterans bear visible signs of their service: a missing limb, a jagged scar, a certain look in the eye.

Others may carry the evidence inside them: a pin holding a bone together, a piece of shrapnel in the leg – or perhaps another sort of inner steel: the soul’s ally forged in the refinery of adversity.

Except in parades, however, the men and women who have kept America safe wear no badge or emblem.

You can’t tell a vet just by looking.

He is the cop on the beat who spent six months in Saudi Arabia sweating two gallons a day making sure the armored personnel carriers didn’t run out of fuel.

He is the barroom loudmouth, dumber than five wooden planks, whose overgrown frat-boy behavior is outweighed a hundred times in the cosmic scales by four hours of exquisite bravery near the 38th parallel.

She – or he – is the nurse who fought against futility and went to sleep sobbing every night for two solid years in Da Nang.

He is the POW who went away one person and came back another – or didn’t come back AT ALL.

He is the Quantico drill instructor who has never seen combat – but has saved countless lives by turning slouchy, no-account rednecks and gang members into Marines, and teaching them to watch each other’s backs.

He is the parade – riding Legionnaire who pins on his ribbons and medals with a prosthetic hand.

He is the career quartermaster who watches the ribbons and medals pass him by.

He is the three anonymous heroes in The Tomb Of The Unknowns, whose presence at the Arlington National Cemetery must forever preserve the memory of all the anonymous heroes whose valor dies unrecognized with them on the battlefield or in the ocean’s sunless deep.

He is the old guy bagging groceries at the supermarket – palsied now and aggravatingly slow – who helped liberate a Nazi death camp and who wishes all day long that his wife were still alive to hold him when the nightmares come.

He is an ordinary and yet an extraordinary human being – a person who offered some of his life’s most vital years in the service of his country, and who sacrificed his ambitions so others would not have to sacrifice theirs.

He is a soldier and a savior and a sword against the darkness, and he is nothing more than the finest, greatest testimony on behalf of the finest, greatest nation ever known.

So remember, each time you see someone who has served our country, just lean over and say Thank You. That’s all most people need, and in most cases it will mean more than any medals they could have been awarded or were awarded.

Two little words that mean a lot, “THANK YOU”.

Thanks for stopping by the site today.

Guest blogger Andrew Healy, an economics professor at Loyola Marymount University, is back and the author of today’s post. As a reminder, there a tag at the site where you can find all of his great work.

Asante Samuel. Jahri Evans. Robert Mathis. These three players share something in common that offers a hint to finding steals in the middle rounds of the draft. All three eventually made Pro Bowls. Each was drafted in Round 4 or later. And each played for a notable football powerhouse in college: Central Florida [1]In 2003, Central Florida went 3-9 in the MAC. While the Blake Bortles Knights may not be a football powerhouse, either, the 2013 UCF team that went 12-1 in the American Conference bears little … Continue reading, Bloomsburg, Alabama A&M.

The success of these smaller college players relative to their marquee school competitors turns out to be a much more general phenomenon. In the middle rounds of the NFL draft, players from outside the traditional power conferences have been more than twice as likely to eventually make the Pro Bowl as players from the most famous programs. On defense, small school players have been even more likely to make the Pro Bowl than their major school counterparts.

Let’s use the 2003 draft as an example. Only 5% (6 out of 116) of the major college players selected in round 4 or later eventually made it to a Pro Bowl. At the same time, 12% (6 out of 50) of small college players would eventually be selected for Hawaii. At the very least, if you were watching the draft and wanting to know what the chances are that your team drafted a future star, those chances increased in the middle of the draft when your team picked a player from a school like Bloomsburg than when it picked another player from the SEC.

In fact, it’s hard to think of anything else that can match the impact of simply picking small-school players as a way to find stars in the middle rounds. The data suggest that this logic has even applied at the top of the draft for comparisons such as those between Buffalo’s Khalil Mack and South Carolina’s Jadeveon Clowney. But the big gains from focusing on smaller football schools have come from finding the gems that the draft buzz mostly bypasses. Consistently, general managers have wasted picks on players from major conferences, missing chances to find difference-makers―particularly on defense―from schools such as Northern Colorado and Idaho State. [2]Bonus points for getting those players. Aaron Smith was a 4th round pick out of Northern Colorado in 1999 and Jared Allen was a 4th round pick out of Idaho State in 2004.

The Data

I look at all players drafted from 1998-2007, stopping at the later year to give players time to make a Pro Bowl. The measure of excellence is making a Pro Bowl, but I’ll also look at All-Pro selections. I ignore players listed at special teams positions (P, K, and KR), although it’s possible you could make a Pro Bowl as a special teamer after being drafted at an offensive or defensive position. I also did not include fullbacks because it became so easy to make the Pro Bowl at that spot.

Major conferences are defined according to the traditional BCS definitions: Big East/American, Big 10, Big 12, Pac 10, SEC, and ACC. Notre Dame is also included with these bigger (in terms of football) schools. A school such as Wake Forest gets defined as a big football school by this measure and it probably shouldn’t be, but adjustments from this definition would be judgment calls and so this simple rule seems best.

Note that almost none of the middle-round small-school Pro Bowlers during this time period come from schools such as Boise State that were big football schools at the time. The two possible exceptions are Brett Keisel of BYU (drafted in 2002) and Paul Soliai of Utah, who was drafted in 2007 before Utah joined the Pac-12.

Comparing Average Success Across Schools

Small school players get drafted later than big school players, so we need to control for draft position to get a fair comparison between them. Later, I’ll use regression to do that. Here, I’m just going to break down results according to ranges of draft position. The chance of making the Pro Bowl is much higher in the early parts of the draft, so I’ll break things down there according to selection number rather than just the round.

The table below looks at the first three rounds of the draft. Overall, the chances of drafting a Pro Bowler tend to be higher for small school players in the first three rounds. The small school samples are limited in the first round, but the share of small school players who make a Pro Bowl is higher throughout than for big schools. Out of all the rounds, the 2nd round is the only one where we see a small trend the other way.

| Small schools | Big schools | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round | # of selections | % Pro Bowlers | # of selections | % Pro Bowlers |

| 1 (Pick 1-10) | 7 | 71.4% | 93 | 55.9% |

| 1 (Pick 11-20) | 8 | 50.0% | 91 | 41.8% |

| 1 (Pick 21-32) | 11 | 45.5% | 99 | 29.3% |

| 2 (Pick 33-48) | 26 | 23.1% | 131 | 24.4% |

| 2 (Pick 49-64) | 35 | 11.4% | 112 | 15.2% |

| 3 | 83 | 10.8% | 244 | 9.0% |

The largest differences, and the clearest benefit from drafting players from smaller schools, come in the middle rounds. The table below shows the differences in rounds 4-7. In round 4 over the ten-year period, teams have been about three times more likely to draft a Pro Bowler when picking from a small school rather than a big one. 12.9% of small school draftees in Round 4 have made the Pro Bowl, compared to just 4.1% of big school players.

| Small schools | Big schools | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round | # of selections | % Pro Bowlers | # of selections | % Pro Bowlers |

| 4 | 93 | 12.9% | 247 | 4.1% |

| 5 | 108 | 8.3% | 228 | 3.5% |

| 6 | 135 | 3.7% | 220 | 3.6% |

| 7 | 157 | 2.6% | 294 | 1.7% |

In round 5, we see a similarly large difference. Round 5 players from small schools have been more than twice as likely as big school players to make a Pro Bowl. Altogether, across rounds 4 and 5, despite 475 non-special teams players being drafted from big schools, just 18 (3.8%) have made a Pro Bowl. On the other hand, out of just 201 players drafted in those rounds from small schools, 21 (10.5%) made a Pro Bowl. If you wanted to find a future star in rounds 4 or 5, you would have increased your chances by more than double by looking at the Northern Colorados and Alabama A&Ms of college football rather than the USCs and Alabamas.

[Chase note: It is at this point that I decided I needed to stop reading the article. I trust Andrew, but found his claims too remarkable to just blindly accept. So I decided to open up my database to confirm. I removed punters and kickers but kept everyone else in the database. To my amazement, the numbers not only seem legit, but perhaps even under-reported. The average player selected from the 4th or 5th round from a Big School made 0.06 Pro Bowls, compared to 0.22 Pro Bowls for players from non-major schools!]

Regression Results: Controlling for Draft Position in a Flexible Way

To figure out the average bonus small school players offer compared to large school players, we can use linear regression to control for draft position. In the regressions, I predict whether a player became a Pro Bowler with a cubic polynomial in draft position and whether the player went to a major school. The regression results indicate that, looking across rounds and controlling for draft position, players from small schools are about 3 percentage points more likely to become Pro Bowlers. [3]We get almost the same result if we include higher powers of the pick number. We also get similar results if we use a logit instead of a linear regression. The standard error for the estimate is in … Continue reading

All rounds ( N = 2427 (0.014)):

The three percentage point bump for small school players is a substantial boost. Across all rounds of the draft, about 11.8% of the main position players made a Pro Bowl. Compared to this baseline, teams increase their chances of drafting a Pro Bowler by about 20% by drafting a small school player.

We can see more of this pattern by breaking things down according to the early and later rounds. If we look at rounds 1-3, nothing statistically significant emerges. The point estimate follows the overall pattern, but the result is not clear, in part due to the relatively small number of small school players drafted in the first three rounds.

Rounds 1-3 (N = 947 (0.034)):

On the other hand, in rounds 4-7, we get a very clear impact of picking small school players, an effect that is even more striking given the much smaller share of players who make the Pro Bowl in those rounds compared to earlier ones.

Round 4-7 (N = 1480 (0.011)):

We see that, controlling for the selection, small school players are 3.3 percentage points more likely to make the Pro Bowl. [4]The t-statistic is 3.04 and the p-value is .002. This represents about a doubling of the chance that a major school player makes the Pro Bowl. Just 3.1% of major school players drafted in Rounds 4-7 at the main positions made the Pro Bowl. The model predicts that around 6.4% of small school players drafted in those same positions would have made the Pro Bowl.

All-Pro Appearances

So focusing on small school players offers a much better way to draft a future star according to Pro Bowl appearances. And it doesn’t look like this is just about Pro Bowls. Instead, it’s pretty clear that small school players perform better more generally than major school players, once we control for draft position, with these differences primarily driven by the middle rounds, particularly 4 and 5.

Small school players drafted in rounds 4-7 are also about twice as likely to appear on an All-Pro team as their major school counterparts. Controlling for draft position, small school players are about 1.3 percentage points more likely to make an All-Pro team, relative to a baseline where 1.5% of major school players made an All-Pro team.

All-Pro (N = 1480 (0.008)):

Particularly given the relatively small number of players who made an All-Pro team, we can look at this another way by considering the number of appearances a player made on an All-Pro team. Controlling for draft position, players drafted in the middle rounds from small schools have an average of .036 more All-Pro selections than major school players. The mean number of All-Pro selections for major school players is .022, so small school players are predicted to have more than twice the number of All-Pro selections as their major school counterparts. [5]The small school players drafted in rounds 4-7 who made an All-Pro team are (with the number of appearances in parentheses): Adalius Thomas (2), Asante Samuel (3), Brandon Marshall (1), Cortland … Continue reading

Number of All-Pro Appearances (N = 1480 (0.015)):

[math]All-Pro Appearances = f(Pick, Pick^2, Pick^3) + 0.036 *Small School [/math]

The Best Defense Comes from Small Schools

One other interesting pattern in the data is the offense/defense breakdown. All of the above effects are driven by the defense. If we look just at offense, there’s basically no difference between big and small schools, which mimics what Chase found using a different methodology last year. However, there are large gaps for defensive players.

Take the regression from before for rounds 4-7. Now let’s break it down separately for offense and defense:

Round 4-7, Offense only (N = 749 (0.016)):

Round 4-7, Defense only (N = 731 (0.015))::

The last gap is pretty enormous. Even if we don’t control for the spot the player is selected―which works against small school players since they get drafted later―we see the huge differences between small and large school defensive players. Out of 499 defensive players drafted in rounds 4-7 from major conference schools between 1998 and 2007, 10 (2.0%) made the Pro Bowl. On the other hand, out of 231 small school players drafted in those same rounds, 18 (7.8%) made the Pro Bowl. The gap for all-pro appearances is similarly large. There were a total of 10 all-pro appearances for the 499 large-school defensive players (.020 per player) and 17 all-pro appearances for the 232 small-school players (.073 per player) drafted in rounds 4-7 during this period.

Even though we have fewer than half as many draftees to pick from compared to major school players, look at the starting 11 we can field from small school players mostly picked in round 4 or later, with two round 3 draftees to fill in a couple of holes:

DE Robert Mathis

DT Paul Soliai

DT Aaron Smith

DE Jared Allen

OLB Joey Porter (3)

MLB Jeremiah Trotter (3)

OLB Adalius Thomas

CB Asante Samuel

CB Cortland Finnegan

FS Kerry Rhodes [6] Rhodes has actually never made a Pro Bowl, but he was second-team All-Pro in 2006. He did not count in the players from small schools who have made a Pro Bowl.

SS Antoine Bethea

Note that if you go back a few more years, you can substitute La’Roi Glover (5th round, 1996, San Diego St.) for Soliai and Rodney Harrison (5th round, 1994, Western Illinois) in at SS, sliding Bethea in for Rhodes at FS. That is a pretty sweet defense, all built on middle-to-late round picks from small schools.

Conclusion

The data show that picks in the middle rounds of the draft have been substantially more productive when spent on players from smaller schools. Despite picking major-school players more than twice as frequently, teams have found as many stars from the smaller schools. On defense, they have actually found substantially more stars from schools such as New Hampshire than ones such as LSU. A defensive player taken in round 4 or later has been almost four times more likely to eventually make a Pro Bowl when that player comes from a school outside the traditional power conferences. Stars such as Jared Allen, Asante Samuel, and Robert Mathis are part of a larger pattern. Teams have found those essential mid-round steals by drafting players from smaller schools.

Why has there been this opportunity to do better by picking small school players? One possibility is that there was less information out there about those players, a gap that would have been decreasing as film and televised college games have become ubiquitous. That explanation makes some sense since the benefit to smaller school players emerges in the middle rounds, long after the Brian Urlachers (New Mexico) and Joe Greenes (North Texas) who were impossible to miss had been selected. However, with the sample going from 1998-2007, this explanation seems unsatisfying since teams have had relatively easy access to information about any college player.

The explanation that I think could make more sense is some kind of risk aversion, kind of like the bias that leads to punts on fourth down. Maybe teams in the middle rounds, not seeing clear standouts, felt that it’s safer to pick the player from Alabama instead of the one from Idaho State. Even though it’s anything but safer, general managers can say to themselves that they’re getting a player who’s a known quantity due to the college program he comes from. Picking the major school player might even be the kind of move that’s harder to criticize, putting the general manager in a similar position to the coach facing 4th and 3 at midfield, where the best choice for the team may not be optimal for the decision maker. Whatever the reason, the bias towards major school players in the middle rounds has left available potential stars to the teams that have chosen players from overlooked schools.

However, this potential opportunity may already be gone. Since 2008, six defensive players have made Pro Bowls and were drafted after round three. All six were actually from major schools: Kam Chancellor (Virginia Tech) and Richard Sherman (Stanford) in Seattle, Geno Atkins (Georgia), Henry Melton (Texas), Alterraun Verner (UCLA), and Greg Hardy (Mississippi). Across offense and defense, it’s eight Pro Bowlers for large schools (adding Carl Nicks and Jordan Cameron) versus four for small schools (Alfred Morris, True Receiving Yards champ Antonio Brown, Josh Sitton, and Julius Thomas, and not counting Jerome Felton, who plays FB), about the same ratio as players drafted altogether. Still, the biggest stars here are clearly the big school players.

Even though we need more years of data on all the players in these drafts, it is possible that the previous trend has shifted. Assuming that’s right, why might that have happened? One possibility is that ever more schools are getting national media attention, meaning that small schools aren’t so small anymore. [7]Another possibility is that NFL teams have changed their behavior. There has been almost no change over time, though, in the share of small school defensive players selected at certain points in the … Continue reading Another possibility that seems even more plausible to me is that the increasing information on high school players means that great players are now less likely to be at small schools in the first place. Even though there will always be some great players who end up at small schools (see Watt, J.J.), maybe Jared Allen would have been recruited more heavily if he played now. There may now be fewer diamonds in the rough than there used to be. That idea suggests there might have been even more diamonds in the rough if we look at earlier years. And that looks like it might be exactly the case. Just looking at rounds 4 and later in some of these earlier drafts is kind of incredible. In 1989, there were five (non-kicker) Pro Bowlers from small schools and only one from a large school. In 1990, there were nine small school Pro Bowlers (including HOFer Shannon Sharpe) compared to just four from major schools. In 1991, it was eight small school Pro Bowlers compared to just two major school players. [8]Some of the late round diamonds in the rough may have become undrafted free agents in later years. For example, James Harrison (Kent State) and London Fletcher (John Carroll) are two small school … Continue reading All of this appears even though substantially more large school players are drafted in rounds 4-8. While the chance to find a small school steal was just on defense from 1998-2007, it seems like the opportunities may have been all over the field in earlier years.

References

| ↑1 | In 2003, Central Florida went 3-9 in the MAC. While the Blake Bortles Knights may not be a football powerhouse, either, the 2013 UCF team that went 12-1 in the American Conference bears little resemblance to where the program was a decade ago. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Bonus points for getting those players. Aaron Smith was a 4th round pick out of Northern Colorado in 1999 and Jared Allen was a 4th round pick out of Idaho State in 2004. |

| ↑3 | We get almost the same result if we include higher powers of the pick number. We also get similar results if we use a logit instead of a linear regression. The standard error for the estimate is in parentheses. |

| ↑4 | The t-statistic is 3.04 and the p-value is .002. |

| ↑5 | The small school players drafted in rounds 4-7 who made an All-Pro team are (with the number of appearances in parentheses): Adalius Thomas (2), Asante Samuel (3), Brandon Marshall (1), Cortland Finnegan (1), Jahri Evans (5), Jared Allen (4), Jerry Azumah (1), Lance Schulters (1), Matt Birk (2), Michael Turner (2), Robert Mathis (1), Terrence McGee (2), and Trent Cole (1). Of these, McGee made it as a special teams player. Amongst major college players drafted in rounds 4-7, Dante Hall and Leon Washington made All-Pro teams as special teamers during this time. |

| ↑6 | Rhodes has actually never made a Pro Bowl, but he was second-team All-Pro in 2006. He did not count in the players from small schools who have made a Pro Bowl. |

| ↑7 | Another possibility is that NFL teams have changed their behavior. There has been almost no change over time, though, in the share of small school defensive players selected at certain points in the draft. |

| ↑8 | Some of the late round diamonds in the rough may have become undrafted free agents in later years. For example, James Harrison (Kent State) and London Fletcher (John Carroll) are two small school UDFAs who made Pro Bowls. |

The NFL Draft is this week, which means we have something resembling real football to talk about. But how much impact will the players who hear their names called during the 2014 Draft have on the 2014 season? Here’s the short answer: as a group, they will make up about 10% of games played by all players and 8% of all starts.

What do I mean by that? Each year, every team’s players start 352 games, which is the product of 16 (games) and 22 (starters). Players selected during the 2013 Draft started 27 games per team last year, which is in line with the recent average of eight percent. I also looked at the number of games played by all drafted rookies, and divided that by the number of games played by all players on that team. Take a look: the blue line represents games played by drafted rookies and the red line represents games started; both numbers on shown on a percentage basis for the league as a whole. [continue reading…]

I can’t tell you how any of the prospects in this year’s draft will turn out, but I can walk you through how the quarterback position has changed over the course of NFL history.

Methodology

For all three variables, I will be using the same methodology to measure “league average” in each season. Each player in each year gets credit for his percentage of league-wide pass attempts in the season multiplied by his value in each variable. For example, when calculating the 2013 league average, Peyton Manning’s [rushing numbers, height, draft position] was worth 3.6% of the league average, while in 1958, Johnny Unitas’s [rushing, height, draft position] was worth 6.7% of the league average. This gives us a weighted average for each variable, weighted by the number of pass attempts by that quarterback. [continue reading…]

Last week at Five Thirty Eight, Nate Silver noted that San Antonio Spurs head coach Gregg Popovich has produced an excellent record against the spread. He also checked in football’s version of Pop, Bill Belichick, and came to the same conclusion: Belichick hasn’t just been great, but he’s been great against the spread, too.

My database on point spreads goes back to 1978, so I went ahead and calculated the Against-The-Spread record of each head coach over the last 36 seasons. According to my numbers, Belichick has “covered” or won 40 more games against the spread than he’s lost, the most over this period. [1]My numbers differ slightly from Silver’s, although that’s not surprising. There is always some variation in point spread data, which is, of course, not official. The table below shows the 122 men who have coached at least 50 games or who were active in 2013.

Here’s how to read Belichick’s line: He has been coaching since 1991 (coaches who began before 1978 are included, but only their post-1977 seasons are counted (and only if they coached 50+ games since 1978)) and was last coaching in 2013. Over that time, he has coached in 332 games, including the post-season. His record against the spread is 182-142-8, which gives him a 0.562 winning percentage (ignoring ties). [2]When calculating regular winning percentage, we treat ties as half-wins and half-losses. In his article, Silver excluded ties from calculating ATS winning percentages. I don’t know … Continue reading His real record is 218-114-0, which gives him a 0.657 winning percentage (again, including the playoffs). The table is sorted by the last category, which represents the difference beteween his number of wins against the spread and his number of losses against the spread. [continue reading…]

References

| ↑1 | My numbers differ slightly from Silver’s, although that’s not surprising. There is always some variation in point spread data, which is, of course, not official. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | When calculating regular winning percentage, we treat ties as half-wins and half-losses. In his article, Silver excluded ties from calculating ATS winning percentages. I don’t know what’s customary, but Silver’s method makes sense: in the event of a “push” all money is simply returns. |

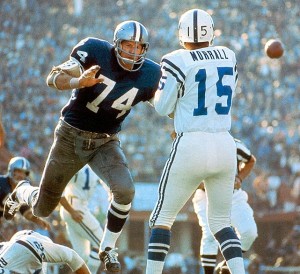

Five days ago, Earl Morrall passed away at the age of 79. His story is well-known to many, but it’s one worth recounting for the uninitiated.

Born in Muskegon, Michigan, Morrall was a star quarterback and baseball player at Michigan State. He made it to the College World Series in 1954 as an infielder, and a year later he guided the Spartans to a 9-1 record as a senior and a victory over UCLA in the Rose Bowl. Morrall was selected by San Francisco with the 2nd overall pick in the 1956 draft, where he sat behind Y.A. Tittle for a year.

In that draft, Pittsburgh used the first overall pick on safety/kicker Gary Glick, who had been a jack of all trades in college, but the team quickly had buyer’s remorse. After the 49ers selected John Brodie with the third pick in the 1957 draft, the Steelers saw an opportunity to acquire Morrall, and did so by sending two future first round picks (and linebacker Marv Matuszak) to the 49ers for Morrall. [1]The trade occurred in September 1957, so the two first round picks were Pittsburgh’s 1958 and 1959 selections. Neither panned out for San Francisco — the players selected were Jim Pace … Continue reading

Why was Pittsburgh so desperate to trade for him? Because Pittsburgh really needed a passer: the only other quarterbacks on the roster at the time were a pair of 22-year-olds named Len Dawson (yes that Len Dawson), whom the Steelers selected with the 5th pick in the ’57 draft, and Jack Kemp (yes that Jack Kemp). The Steelers knew you couldn’t count on young quarterbacks — the team released a 22-year-old Johnny Unitas two years earlier — which explains the trade with the 49ers. As a reminder, just about everything Pittsburgh did before 1970 was a disaster.

Morrall produced solid numbers as the Steelers starter in ’57, but threw seven interceptions in his first two starts with the Steelers in 1958. Pittsburgh’s head coach at the time was Buddy Parker, who had coached the Lions from 1951 to 1956. Parker was not content to turn the job over to Dawson, so he traded Morrall and a pair of picks [2]One of whom likely turned into the great Roger Brown to Detroit for his old quarterback, Bobby Layne. [continue reading…]

References

| ↑1 | The trade occurred in September 1957, so the two first round picks were Pittsburgh’s 1958 and 1959 selections. Neither panned out for San Francisco — the players selected were Jim Pace and Dan James. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | One of whom likely turned into the great Roger Brown |

Yesterday, I looked at team turnover in the passing game for every team in 2013. You can review the pretty complicated [1]While I admit to it being complicated, I think the added value in accuracy is worth the added layer of complexity; frankly, I can’t think of a simple way to calculate turnover that really … Continue reading formula in that post, but the short version is to give each player credit for the lower of two values: his percentage of team receiving yards in Year N and his percentage of team yards in Year N-1. Today, I use that same concept to analyze team passing for every year since the merger.

And the team with the greatest receiving turnover in NFL history (even including pre-1970 teams) is the 1989 Detroit Lions. Take a look at the players who caught passes for Detroit in 1988:

| Receiving | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Age | Pos | G | GS | Rec | Yds | TD | |||

| 82 | Pete Mandley | 27 | PR/WR | 15 | 14 | 44 | 617 | 14.0 | 4 | 41.1 |

| 33 | Garry James | 25 | RB | 16 | 16 | 39 | 382 | 9.8 | 2 | 23.9 |

| 80 | Carl Bland | 27 | wr | 16 | 2 | 21 | 307 | 14.6 | 2 | 19.2 |

| 89 | Jeff Chadwick | 28 | WR | 10 | 8 | 20 | 304 | 15.2 | 3 | 30.4 |

| 83 | Gary Lee | 23 | KR/wr | 14 | 6 | 22 | 261 | 11.9 | 1 | 18.6 |

| 30 | James Jones | 27 | FB | 14 | 14 | 29 | 259 | 8.9 | 0 | 18.5 |

| 87 | Pat Carter | 22 | TE | 15 | 14 | 13 | 145 | 11.2 | 0 | 9.7 |

| 49 | Tony Paige | 26 | rb | 16 | 2 | 11 | 100 | 9.1 | 0 | 6.3 |

| 81 | Stephen Starring | 27 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 89 | 17.8 | 0 | 14.8 | |

| 38 | Scott Williams | 26 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 46 | 15.3 | 0 | 4.2 | |

| 81 | Mark Lewis | 27 | te | 3 | 3 | 3 | 32 | 10.7 | 1 | 10.7 |

| 41 | Paco Craig | 23 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 29 | 14.5 | 0 | 3.6 | |

| 26 | Carl Painter | 24 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.1 | |

| Team Total | 26.2 | 16 | 213 | 2572 | 12.1 | 13 | 160.8 | |||

References

| ↑1 | While I admit to it being complicated, I think the added value in accuracy is worth the added layer of complexity; frankly, I can’t think of a simple way to calculate turnover that really captures what analysts value. |

|---|