A couple of weeks ago, Andrew Healy contributed a guest post titled, “One Play Away.” He’s back at it today, and we thank him for another generous contribution. Andrew Healy is an economics professor at Loyola Marymount University. He is a big fan of the New England Patriots and Joe Benigno.

What teams do we remember the most? Going back to the merger, the 1970s Steelers, the 1980s 49ers, the 1990s Cowboys, and the 2000s Patriots seem to stand above the rest. Each of these teams earned that place in our collective memory by winning the most Super Bowls in the decade.

How different could it have been? In other words, were the dynasties that happened by far the most likely ones? Or were there others that were equally, or even more likely? Think of teams that have suffered unusually cruel sequences of defeats (cue nodding Vikings, Bills, and Browns fans). We all know that those teams could have won Super Bowls. But maybe the more interesting question is whether those teams realistically could have won multiple Super Bowls, or even have become the dominant team of the era.

Today, I estimate the chances that different teams had of becoming the Team of the Decade (the TOD) for the ’70s, ’80, ’90s, and ’00s. Some of the results are surprising. One of the teams that became the TOD was actually much less likely than another to dominate that decade. Only two of the four teams truly stand out as being clearly the single most-likely team to be the TOD.

Even more interesting are the teams that might have been dynasties instead of the ones we’ve come to know. In most cases, these teams won at least one Super Bowl. In one case, though, a team that became famous for losing easily could have been not just a one-time winner, but a team that became a dynasty and dominated the decade.

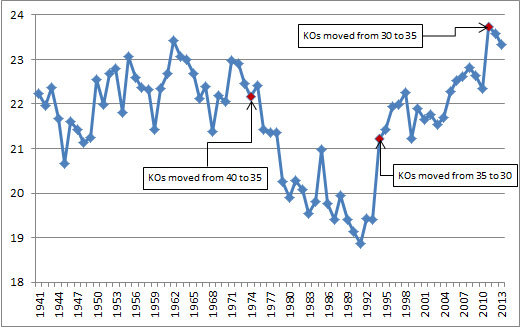

To come up with the estimates of a team’s chances of winning Super Bowl, I simulated the playoffs 50,000 times. I used the actual playoff brackets and then created win probabilities for each game based on team strength. In tables that follow below, I’ll describe the probabilities that teams won multiple titles in a decade. I’ll also pick a True Team of the Decade (most expected Super Bowl wins), a What-Might-Have-Been-Dynasty that Won Nothing, a Team that Wasn’t as Good as We Remember, and a A Bottom-Feeder Team(s) for each decade.

First, a brief description of how I performed the simulations before getting to the rankings:

- The playoffs were run under the rules in a given year: All rules relating to seeding, home field, and number of teams were used. If there was a rule in place preventing matchups between divisional opponents in a given round, I also applied that rule. To some extent, the fewer teams in earlier years helped make dynasties more likely in those decades.

- Pro Football Reference’s Simple Rating System was used to measure team strength: I used PFR’s for all years to be consistent. It’s worth noting that their ratings and DVOA usually match up closely. Another possibility is to try to simulate DVOA ratings, but it seems simpler to just use SRS throughout. In some cases, there are some differences, such as for the 1998 Broncos and 1999 Titans.

- I used the beginning of the NFL season to define the decades: So 1970-79 means Super Bowls V-XIV. An interesting thought experiment is to consider Super Bowl time instead of calendar decades. Then the Raiders would have been the team of Super Bowls XI-XX. Anyway, I’ll stick with the convention. It’s worth noting that my results suggest the Raiders were not as good as we might remember.

1970s

The table below shows each franchise’s probability of having won 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 Super Bowls during the decade according to the methodology described above. The final column shows the expected number of Super Bowl wins for the decade.

The True Team of the Decade: Pittsburgh Steelers

The Steelers had only a 14.5% chance of winning no Super Bowls in the ’70s and a 4.9% chance of winning the four that they did. The expected value of SB wins for Pittsburgh was 1.67, the highest value for any team in any decade.

The What-Might-Have-Been-Dynasty that Won Nothing: Minnesota Vikings

The Vikings are not too far away from the Steelers and Cowboys. There was only a 23.6% chance the Vikings would have won nothing in the ’70s. And they certainly could have won multiple championships. There was over a 35% chance the Vikings would have won at least two titles and a 9.6% chance they would have won at least three. Of all the teams that won nothing, the 1970s Vikings are the best candidate for the team that could have been the TOD.

The What-Might-Have-Been Dynasty that Won Nothing, Part 2: Los Angeles Rams

A little bit behind the Vikings are the Rams. Los Angeles had only a 39% chance of winning no Super Bowls in the ’70s and a 20.3% chance of winning multiple titles.

The Team that Wasn’t as Good as We Remember: Oakland Raiders

When I starting working with the data, I expected the Raiders to challenge for the TOD. Five losses in the AFC championship to go with the one title. Seven playoff appearances. Despite all that, the Raiders only had the sixth-most expected titles in the decade. In fact, they didn’t really underperform at all in terms of titles. They had a 39.5% chance of winning none at all. The Raiders’ SRS ratings explain this. Oakland was never really great, only passing +10.0 in a year (1977) where they finished second in the division.

Bottom-Feeder Teams: New York Giants, New York Jets

Only two teams played the entire decade and missed the playoffs every single year. They happened to be the two teams that played in New York. The chance that two teams would miss the playoffs every year and New York would happen to miss playoff football entirely: about 0.2%.

1980s

The True Team of the Decade: San Francisco 49ers

Unlike the 1970s, the ’80s weren’t close. The Niners were similar to the ’70s Steelers with an expectation of 1.64 Super Bowl wins in the decade. The ’80s 49ers had about a 4.2% chance of winning the four Super Bowls they did and 51.7% chance of winning at least two. And, while not shown in the table above, it’s exciting to note that the Niners had a 0.004% chance of winning seven Super Bowls in the 1980s.

The What-Might-Have-Been-Dynasty that Won Nothing: Miami Dolphins

I was really surprised by this one. The Dolphins come in third in the 1980s in expected SB wins with 0.81. Based on their consistency in the first half of the decade, the Dolphins had an 18.6% chance of winning multiple Super Bowls in the 1980s. That’s substantially higher than the 12.4% chance for their nearest competitor: the much better-remembered Denver Broncos who were annihilated in three Super Bowls.

The Team that Wasn’t as Good as We Remember: Oakland/LA Raiders

Despite never being close to dominant, the Raiders won two Super Bowls in the 1980s. According to the number of SB wins we would have expected them to have, the Raiders actually rank 11th, behind six teams that won none in the decade. They had about a 5.5% chance of winning multiple titles in the decade.

A Bottom-Feeder Team: Houston Oilers

For teams that played every season since the merger, the Oilers had the least hope of winning a title over the 1970s and 1980s combined. That’s a little surprising given that they had at least one memorable moment in the playoffs during that stretch, unlike some of the teams ahead of them.

1990s

The True Team of the Decade: San Francisco 49ers

This one almost leaps off the page. Not only were the Niners on top in the 1990s in terms of expected SB wins, they were way on top. Given the Cowboys’ relatively short run, it’s not surprising that they would do worse here, but they’re closer to the 10th place Rams on this list than they are to the 49ers. Even though they only won one in the decade, the Niners had the same number (1.64) of expected titles in the ’90s as they did in the ’80s, and a 51.7% chance of multiple titles.

The What-Might-Have-Been-Dynasty that Won Nothing: Buffalo Bills

The Bills actually do worse on this list than I would have expected. They were about even money to win the zero titles that they did in the ’90s. They had an 11.0% chance of winning multiple titles, making them the top-ranked no-title team of the ’90s, but ranking them well behind the ’70s Vikings, the ’70s Rams, and the ’80s Dolphins.

The What-Might-Have-Been-Dynasty that Won Nothing, Part 2: Kansas City Chiefs

On the field, the ’90s Chiefs only went to one AFC Championship game and no Super Bowls. Nevertheless, they’re about even with the Bills in terms of the Super Bowls they could have won. They had a 10.4% chance of winning multiple titles in the ’90s.

The Team that Wasn’t as Good as We Remember: Pittsburgh Steelers

I’m not sure there’s a great candidate in this category, so I was tempted to just pick the Raiders again to keep the pattern. You could go with Broncos here, but the 1998 Broncos are one case where there’s a clear gap between SRS and DVOA, which gives them more credit. The ’90s Steelers had four playoff byes in a run of six straight playoff appearances. Still, they had a 59.3% chance of winning no Super Bowls and only a 7.9% chance of winning multiple titles.

A Bottom-Feeder Team: Phoenix/Arizona Cardinals

The worst team in two consecutive decades. Over twenty years, the Cardinals had 0.003 expected titles. That’s only 0.003 more expected titles than the Houston Texans and they weren’t even in the league yet.

2000s

The True Team of the Decade: New England Patriots

Less dominant than the other True TODs, the Patriots of the aughts still have a healthy gap over their closest rival, the Colts. There was only a 17% chance the Patriots would have gotten shut out in the ’00s. There was a 41.7% chance that the Pats would win multiple titles in the decade, more than double the chance of any other team.

The What-Might-Have-Been-Dynasty that Won Nothing: Philadelphia Eagles

The Eagles rank third in expected titles in the ’00s with 0.78, just a hair behind the Colts for second. They also look similar to the 1970s Rams and 1980s Dolphins in terms of multiple-title potential. They had about a 17.4% chance of winning multiple titles in the aughts.

The Team that Wasn’t as Good as We Remember: Tampa Bay Buccaneers

Hopefully, it’s not too hard to remember a decade that ended with President Obama in the White House, but the Bucs come in lower here than I might have guessed. They made the playoffs five times, but still are only 14th in expected SB wins. They actually had a 71% chance of winning no titles in the decade. Even in their best year, 2002, where they ranked #2 in SRS and #1 in DVOA, they were far from dominant and so had only about a 21% chance of winning the title.

Bottom-Feeder Teams: Buffalo Bills, Detroit Lions

Neither team made the playoffs in the decade, a more impressive accomplishment than the ’70s Giants and Jets in an era of expanded playoffs. Both cities also suffered through deindustrialization and so seemed to deserve better football as a compensating differential.

Closing Thoughts

I was excited to check this out because I wanted to compare teams like the ’90s Bills and the ’70s Rams. That comparison makes it pretty clear that the ’70s Vikings are hands-down the clearest What-Might-Have-Been-Dynasty that Won Nothing. This is all post-merger, so arguably the best Vikings team of that era (the ’69 edition) doesn’t even count in the calculation. If you count the 1969 Vikings, there was only about a 1-in-6 chance that those Vikings would end up with no Super Bowls.

Maybe the most remarkable regularity over the years is how the Cardinals have been so bad for so long. Even though Arizona came close in 2008, the Cardinals had only an 11.2% chance of winning any of the last 44 Super Bowls. In fact, they were lucky just to make the one Super Bowl that they did (in more ways than one).

Finally, a couple of thoughts about this decade. While we’re only four years in, this decade could wind up resembling the 1990s. The Patriots right now are playing the role of the ’90s Niners, while the Seahawks may be the best candidate to be the Cowboys. So far, the Patriots have been (perhaps surprisingly) dominant. There’s only about a 27% chance that New England would have no titles in the 2010s and there was even a 28.5% chance that the Patriots would have already won multiple titles; that likelihood is more than four times more as any other team. Despite having none on the field through four seasons, the ’10s Patriots are on pace through four years to have the most expected SB wins for any decade. They already have 1.07 expected wins, more than double their nearest competitor.