Denver has scored at a historic rate.

Today’s insane statistic comes courtesy of

RJ Bell: the difference between Denver and the #2 team in points per game

is larger than the difference between the #2 and #31 teams. The Broncos are averaging 39.8 points per game this season, 11.6 points more than the (

surprisingly second-ranked) Bears. And Chicago is averaging just 9.9 more points per game than the Jets, the #31 ranked scoring team.

That is, well, crazy. The record for points per game in a season is 38.8, set by the 1950 Rams. The 2007 Patriots are second at 36.8, and both of those teams scored slightly more points through ten games than the 2013 Broncos. So while Denver is on pace to break the scoring record, some regression to the mean over the final six games should be expected.

If the Broncos want to set the record for most points scored relative to the second highest scoring team in the league, Peyton Manning and company have some work to do. That mark is held by the ’41 Bears, who averaged 36.0 points per game, 12.5 more than the Packers that year. Second and third on that list are the ’07 Patriots (8.4) and ’50 Rams (8.3), so Denver has a realistic shot of setting the modern record.

I’ll be honest: as dominant as the Broncos offense has been, I’m a little surprised to see them so far ahead of the competition in points scored. After all, consider:

- The Eagles have just 19 fewer yards than the Broncos, and Nick Foles actually leads Manning in both passer rating and Adjusted Net Yards per Attempt;

- In PFR’s Expected Points Added, the Broncos offense is at 14.7 EPA-added per game, while the Saints offense is at 11.3. That’s a relatively small difference considering the fact that Denver has scored 12.1 more points per game than New Orleans.

- The Chargers have a higher completion percentage than the Broncos and six fewer turnovers, but have averaged 17 fewer points per game.

- The Packers are actually a hair ahead of Denver in yards per play (6.3531 to 6.3529), but have scored two fewer touchdowns per game.

So what’s going on? I’m perfectly fine with Denver being general run-of-the-mill dominant, but the team’s points scored numbers makes it seem like the Broncos might be the greatest offensive machine ever. I think I’ve identified the two reasons to explain the gap:

Red Zone success

Philadelphia has scored a touchdown just 46% of the time the Eagles made it into the red zone, which ranks 28th in the league. San Diego isn’t much better at 50% (22nd). The Saints are at 52.5% (20th), and the Packers are down at 30th at 43%. So some excellent offenses are really struggling in the red zone, which gives them disproportionately low points per game averages. Oh, and Denver? They’re at 79.1%, by far the highest rate in the league. It’s not unusual for a great offense to dominate in the red zone — the ’07 Pats were at 70% — but what is unusual is seeing the other top offenses struggle there.

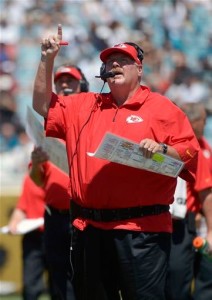

I have red zone data going back to 1997, and the highest ever performance was set by Kansas City in 2003. The Trent Green–Priest Holmes–Tony Gonzalez Chiefs scored a touchdown on 77.8% of all red zone opportunities (42 out of 54), so the Broncos (34 out of 43) could break that record this year. More likely, though, is that the Broncos go from otherworldly in the red zone to just great, which would drop the team’s points per game average.

Number of Drives

The Broncos are averaging 2.85 points per drive, while the Saints are #2 at 2.46. That’s not a huge difference — the gap between #2 and #7 is slightly bigger. The difference, as you can deduce, is that the Broncos are averaging 13 drives per game while the Saints are at just 11.3 drives per game. Why is that? New Orleans’ average drive takes 2:56 minutes, the third-longest in the league (and San Diego is #1 at 3:13), while the Broncos are in the bottom five at 2:17 (the Eagles are last at 2:02). That Chip Kelly edge is erased, though, because Philadelphia’s opponents average 2:48 per drive, the third highest rate in the league. Denver’s opponents take just 2:18 per drive, the third lowest (just a second ahead of Detroit and eight seconds longer than Kansas City).

The Broncos defense is not great, but it does rank 6th in completion percentage allowed. Combine that with the fact that Denver ranks 4th in percentage of opponent plays that are passes, and incomplete passes occur on 25% of all plays run by Broncos opponents, the second-highest rate in the league behind Kansas City. That’s not surprising for a team with such a high Game Script, but it does stop the clock from running for long stretches, which gives Denver’s offense more possessions The Chargers are 28th in this statistic (18%), which is one reason why San Diego is dead last in offensive drives (10.2 per game).

But there’s another reason why Broncos’ opponents tend to have short drives: Denver leads the league in 20+ yard plays allowed at 54. As a result, teams don’t end up with many clock-chewing drives against Denver: opponents tend to gain big yards quickly or throw incomplete passes. That increases the number of drives for the Broncos, which (one could argue) inflates the success of the team’s offense. It’s all relative, of course — Denver is still #1 in points per drive by a wide margin — but it’s worth recognizing that Denver has scored 75% more points per game than an average of the other 31 teams, but “just” 62% more on a per-drive basis. That accounts for about 3 points per game. Add in the insane success in the red zone, and the lack of success there by the other top teams, and you have the reasons for the crazy stat at the top of today’s post.

Manning Record Watch Update

After six games, I analyzed how likely Manning was to break the single-season touchdown record. At the time, he had 22 touchdowns, and the formula projected him to throw 2.99 TDs/G the rest of the way to finish with 52 touchdowns, narrowly breaking Tom Brady’s record.

Now? Manning has 34 touchdowns, as his pace has only slightly declined. What does that mean? To calculate Manning’s odds using Bayes Theorem we need to know four things:

1) His Bayesian prior mean (i.e., his historical average): 2.38, as this number wouldn’t change from the original post.

2) His Bayesian prior variance (the variance surrounding his historical average): Again, no change here, so we use 0.0986.

3) His observed mean: Instead of 3.667, we will use 3.4.

4) His observed variance: This one involves just a little bit of work. What I suggested we do last time is calculate the number of passing touchdowns per game Manning averaged in the first six (now ten) games of each season since 2000, along with his average over the rest of the season (then, 8-10 games, now, 4-6 games). Then we take the difference of the variances of each column, as we did in step two.

Manning’s variance over the rest of the season is 0.3052 TDs/G, while his variance through ten games is 0.2214; the differential there is 0.0838, which is the variance of our current mean.

Once you have your number for these four variables, then you substitute those numbers into this equation:

Result_mean = [(prior_mean/prior_variance)+(observed_mean/observed_variance)]/[(1/prior_variance)+(1/observed_variance)]

Or, using our numbers:

[(2.38 /0.0986) + (3.4 / 0.0838)] / [(1/0.0986) + (1/0.0838)]

which becomes

[24.14 + 40.57] / (22.08) = 2.93

This picture will never get old.

After averaging 3.667 TDs/G over 6 games, we projected Manning to average 2.99 TDs/G the rest of the year. Since he averaged “only” 3 touchdowns per game over his next four games, we downgrade him from 2.99 to 2.93. Of course, we already had a significant regression factored into his future projection — we dropped him by 0.67 TDs/game from his average, which is the point of using Bayes Theorem. So while he’s at “only” 3.4 TDs/G on the season after 10 games, since he’s played at that level for longer, he only loses about half a touchdown per game over his projection the rest of the way.

That gives Manning 17-18 touchdowns, which puts him at a season-ending projection of 51-52 touchdowns. He’s still more likely than not to break the record, although obviously this analysis ignores lots of elements like strength of schedule. And with a visit to Kansas City and a game against the Titans (who have allowed a league-low 7 touchdowns through the air), perhaps he’s actually an underdog to even tie Brady at 50.