Over at Footballguys.com, I analyzed how the fantasy value of quarterbacks, running backs, wide receivers, and tight ends have changed since 1990. The NFL is a very different beast than it was 23 years ago, but you might be surprised to see what that means for fantasy football. To measure value, I examined the VBD curves for each of the four major positions in fantasy football.

For those unfamiliar with VBD, you can read Joe Bryant’s landmark article here. The guiding principle is that the value of a player is determined not by the number of points he scores but by how much he outscores his peers at his particular position. This means that in a league that starts 12 quarterbacks, each quarterback’s VBD score is the difference between his fantasy points and the fantasy points scored by the 12th best quarterback. The cut-offs at the other positions are 12, 24, and 36, for tight ends, running backs, and wide receivers, respectively.

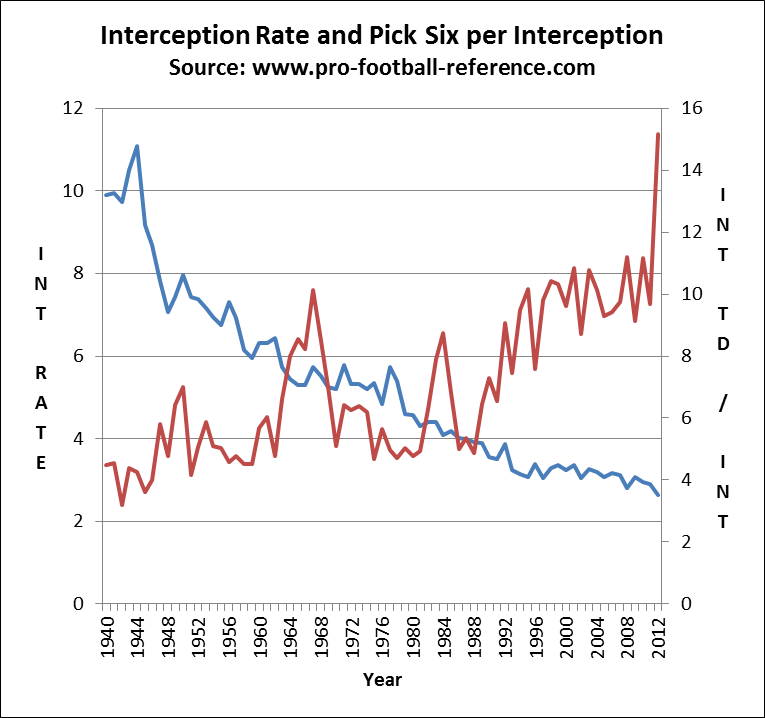

The NFL in 2013 won’t closely resemble how the league looked in 1990, but what does that mean for fantasy football? To determine that, we need to see if VBD has evolved with the rest of the football statistics. Let’s start with a graph displaying number of fantasy points scored by the last starter at each position since 1990. As you can see, quarterback scoring has risen significantly over the last two decades, and the production of the 12th tight end has nearly doubled over that time period.

You can see the full article here.