One of the very first posts at Football Perspective measured how various passing stats were correlated with wins. One of the main conclusions from that post was that passer rating, because of its heavy emphasis on completion percentage and interception rate, was not the ideal way to measure quarterback play. But what about ESPN’s Total QBR, a statistic invented specifically to improve on — and supersede — traditional passer rating?

As a reminder, we can’t simply correlate a statistic with wins to determine the utility of that metric. The simplest way to remember this is that 4th quarter kneeldowns are highly correlated with wins. Just because you notice it’s raining when the ground is wet doesn’t mean a wet ground causes rain; i.e., just because two variables are correlated doesn’t mean variable A leads to variable B (alternatively, variable B could lead to variable A, variable C could lead to both variable A and B, or the sample size could be too small to determine any legitimate causal relationship). That said, it at least makes sense to begin with a look at how various statistics have correlate with wins.

The Sample Set

Throughout this post, I will be looking at a set of quarterback data consisting of the 152 quarterback seasons from 2006 to 2013 where the player had at least 14 games with 20+ action plays. Games where the quarterback had fewer than 20 plays were excluded, but the quarterback was still included if he otherwise had 14 such games.

The next step was to sum the weekly quarterback data on various metrics, including wins, and create season data. This allowed me to measure the correlation between a quarterback’s statistics over those 14+ games with that player’s winning percentage in those games.

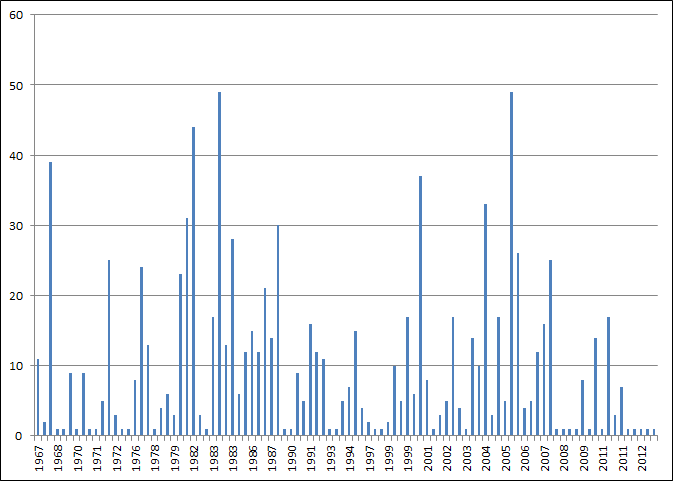

As it turns out, ESPN’s Total QBR is very highly correlated with wins, with a 0.68 correlation coefficient. This is to be expected; after all, Total QBR is based off Expected Points Added on the team level, which generally tracks wins and losses. The second most correlated statistic with wins was Adjusted Net Yards per Attempt, my favorite non-proprietary quarterback metric. After ANY/A, both traditional passer rating and touchdowns per attempt were the next most correlated statistics with wins (after all, this is only a step or two away from saying scoring points is correlated with wins). In another unsurprising result, passing yards had almost no correlation with wins, while pass attempts had a slight negative correlation (as any Game Scripts observer would know). Take a look:

When ESPN first introduced QBR, I wrote that I was intrigued by the possibility of this metric, but frustrated that the specific details of the formula remained confidential. At the time, a clutch weight feature was included in the calculations, which made the metric more of a retrodictive statistic than a predictive one. Since then, ESPN has tweaked the formula several times, and the clutch weight has been capped. ESPN is not engaged in academia, so I understand why they have not published all the fine print; as a researcher, I’m still frustrated by that decision. Still, with 8 years of QBR data now publicly available, we can answer two questions: does Total QBR predict wins and how sticky is Total QBR?

We know that a high Total QBR is correlated with winning games, but we also know that there’s limited value to such a statement. If having a high Total QBR was one of the driving factor behind winning games, than such a variable would manifest itself in all games, not just the current one. So with my sample of 152 quarterbacks, I used a random number generator to divide each quarterback season into two half-seasons. Then I calculated each quarterback’s average in several different categories and measured the correlation between a quarterback’s average in such category in each half-season with his winning percentage in the other half-season. The results:

As you would expect, all of our correlations are now smaller. But ESPN’s quarterback rating metric remains the best measure to predict wins. Perhaps even more impressively, Total QBR is more correlated with future wins than past wins. That’s pretty interesting. Another interesting result is that passer rating fares pretty well here, although much of the same issues as before remain with using correlation to derive causal direction.

One other concept to remember is that our sample of quarterbacks consists of players who were heavily involved in at least 14 games. That makes sure Peyton Manning, Tom Brady, and Drew Brees are involved, while filtering out some Christian Ponder, Blaine Gabbert, and Brandon Weeden seasons. In other words, the data set contains more above-average quarterbacks than a random sample would, so we may not be able to justify certain conclusions from this study.

The other important question is whether Total QBR is predictive of itself; i.e., how “sticky” is this metric over different time periods. We know that interceptions are very random, and knowing a quarterback’s prior interception rate is not all that helpful in predicting his future interception rate. Where does Total QBR fall along those lines?

The most “sticky” stats were passing yards and pass attempts, which in retrospect isn’t too surprising. These reflect the style of the offense, the talent of the quarterback, and the quality of the defense, so they should be easier to predict. The second-least sticky metric was wins, which also makes sense. After that, ESPN’s Total QBR fits in a narrow tier with most of our other metrics as being somewhat predictable.

Conclusion

The numbers here indicate that Total QBR is worth examining. It may be a proprietary measure of quarterback play, but it’s not a subjective one with no basis in reality. It does seem to be the “best” measure of quarterback play, although whether the tradeoff in accuracy for transparency is worth it remains up to each individual reader. One of the drawbacks I see in Total QBR is the failure to incorporate strength of schedule. And while no other traditional passer metric does, either, it’s also easy enough to make those adjustments. Hopefully, an SOS-adjusted Total QBR measure will be released soon (I’ll note that the college football version does include a strength-of-schedule adjustment). My sense is that Total QBR is underutilized because (1) ESPN haters hate it because it’s an ESPN statistic, (2) it’s proprietary, and (3) analytics types disliked it because of the (now-eliminated) clutch rating. While I would not suggest making it the only tool at your disposal, it does appear to deserve a prominent place in your toolbox.