I’ve written several histories of NFL career records, but the history of the career receiving touchdowns record is the most fascinating to me. Twelve men held the receptions title, and eleven held the receiving yards record. Seven different players held the record for rushing yards and for rushing touchdowns. Eleven quarterbacks held the passing yardage crown, while ten captured the touchdown title. This record is different. Thanks, primarily, to Don Hutson and Jerry Rice, only four players have held the record for receiving touchdowns since the NFL started keeping official statistics in 1932.

I’ve written several histories of NFL career records, but the history of the career receiving touchdowns record is the most fascinating to me. Twelve men held the receptions title, and eleven held the receiving yards record. Seven different players held the record for rushing yards and for rushing touchdowns. Eleven quarterbacks held the passing yardage crown, while ten captured the touchdown title. This record is different. Thanks, primarily, to Don Hutson and Jerry Rice, only four players have held the record for receiving touchdowns since the NFL started keeping official statistics in 1932.

Receivers to Hold the Career Receiving Touchdowns Record

Johnny Blood (7 years as record-holder)

By the end of 1932, the first season in the official NFL record book, Blood had scored 25 receiving touchdowns. Most of those occurred in the “pre-stat” era, with 22 of his scores coming between 1926 and 1931. That includes a career high (by far) eleven touchdowns in 1931—he never had another season with more than five touchdowns. He played until 1938, slowly racking up touchdowns and retiring with 37 through the air.

Don Hutson (49 years, 3 months as record-holder)

Huston finished the 1939 season with 36 receiving touchdowns, just one shy of Blood’s record. To begin 1940, he tied the record in the third quarter of a blowout loss to the Bears, and he broke it in the opening quarter of a blowout win over the Cardinals. He got a fortunate break when WW2 took much of the talent from the NFL; during the war-depleted years, Hutson had by far his most productive touchdown seasons (1941-43 were his only three season with double-digit receiving scores). He ended his career with 99 receiving touchdowns, a number that wasn’t approached for decades.

Steve Largent (3 years as record-holder)

Largent was two touchdowns shy of the record coming into the 1989 season. Things looked dim for the receiver, who scored in week one but followed with ten straight weeks in which he failed to find the end zone. However, he was able to tie the record in game twelve and subsequently break it in week 14. The last touchdown of his storied Hall of Fame career was the one that gave him sole possession of the record. He didn’t hold the record for long, because the most prolific player of all time was already on his heels.

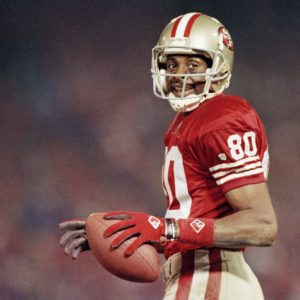

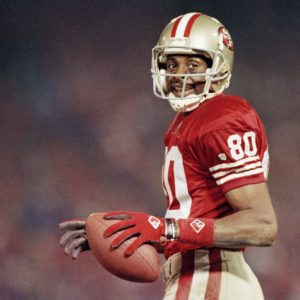

Jerry Rice (27 years, 10 months as record-holder, so far)

Through seven seasons (1985-91), Rice had already compiled 93 receiving touchdowns. In week 12 of 1992, Rice tied Largent’s record in a victory over the Eagles. The following week, in a dominant win over the Dolphins, World gained sole possession of the record, becoming the first player in history to top the century mark. He added an incredible 96 touchdowns after that, walking away with 197 and a distant lead over anyone before or since.

Future of the Career Receiving Touchdowns Record

This record seems like it’s going to last for a pretty long time. As of today, the top ten active leaders in touchdowns are:

Larry Fitzgerald – 120

Rob Gronkowski – 79

Jimmy Graham – 75

Antonio Brown – 75

Jason Witten – 72

A.J. Green – 63

Demaryius Thomas – 63

Greg Olsen – 60

Julio Jones – 57

DeSean Jackson – 55

DeAndre Hopkins – 55

Fitzgerald is 37 and is still 77 touchdowns short of the record. Gronk needs 118 to tie, which would more than double his career output to date. Given his injury history, it’s a little outlandish to expect him to come anywhere close. Graham is 122 shy and is just not very good anymore, and he hasn’t been for some time now. Brown is also 122 away, and he is both 32 years old and out of the league for being a total head case.

Witten has looked and played like an old man since he entered the league. Green looks like he aged a decade overnight. Thomas can’t find a team, and Olsen looks his age. Jones famously doesn’t score touchdowns, while Jackson is 33 and not the threat he once was.

Looking for younger players on the right track, I don’t see anyone. But let’s discuss a few anyway. How about DeAndre Hopkins, Mike Evans, Odell Beckham Jr., Davante Adams, and Travis Kelce.

Hopkins is 28 and has 55 touchdowns. His career high was 13 in 2017. For reference, Rice had eight seasons with at least that many touchdowns (and six with more). He’d have to replicate his best season eleven times to own the record!

Evans is just 27, and he has 50 scores. He has also only had two seasons in which he played the full 16 games. With 9 touchdowns per 16 games over his career, he’d have to reproduce his career average—without missing a game—for over 15 more years. Or average 14.7 touchdowns a year over the next decade.

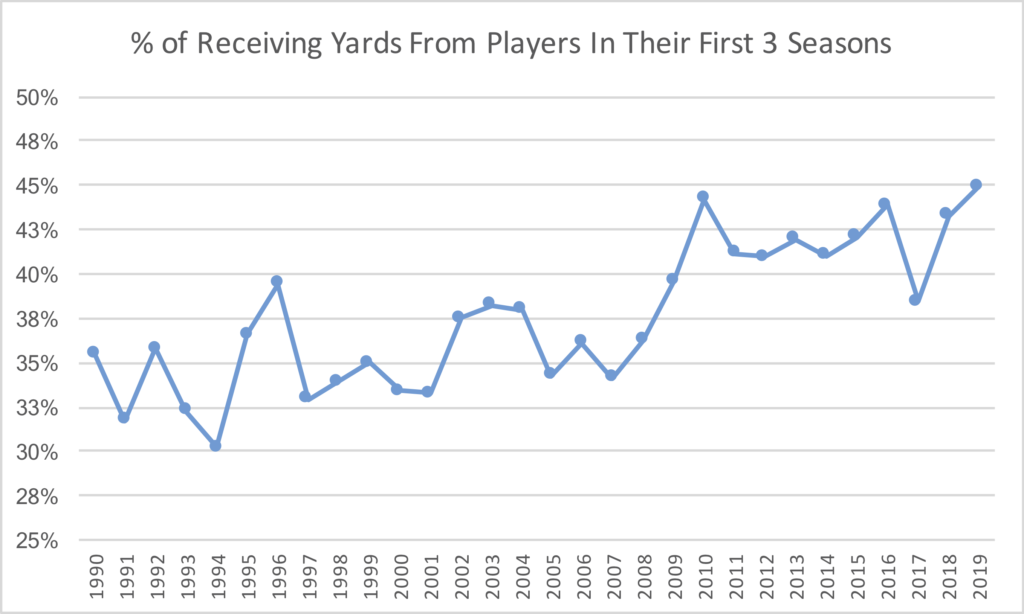

Beckham started his career on fire, scoring 35 touchdowns in his first three seasons. He’s one of just six players in history to accomplish that. But from 2017 to present, he has played in just 34 games and scored a mere 14 touchdowns. That means after his tremendous start he is now 148 touchdowns short of the record with no signs of reclaiming past glory.

Adams is 28 and has 46 touchdowns. Most of that came from 2016-28, during which time he scored 35 times. He had a down year in 2019, scoring just five touchdowns. That might not seem like an issue, but things have to go perfectly to take the crown from the king. Rice started slow with three touchdowns, but after that, he didn’t have a season as low as five until he was 35 years old and played in just two games. During his “peakiest” peak, from ages 24-33, his touchdown output looked like something from a video game: 15, 22, 9 (his down year), 17, 13, 14, 10, 15, 13, and 15.

Kelce will be 31 in a few weeks. He’s a scoring machine for a tight end, but with 38 touchdowns he is still 159 shy of Rice. If he was guaranteed to match his career high every year until he broke the record, he’d have to play until he was 47.

Maybe Reek Hill is a sleeper. He is a big play threat and a favorite target of a guy who throws a lot of touchdown passes. I don’t think he stands a chance. At 26, he’s already older than he seems. And he has just 33 touchdowns. Rice had 49 by that age and added 97 over the following seven seasons. Then he threw in another 51 just for funsies.

What I’m saying is this: I don’t believe any active player will break Rice’s record, even with expanded schedules.