Two years ago, I set a baseline for what a pre-season projection system should hope to accomplish. The simplest baseline of all would be to project each team to go 8-8. That would require no thought at all: a person could wake up 49 years and eight months from now and project each then-existing team in the NFL (or its successor league) to go .500 in the 2067 season. So any projection system has to beat that, at a minimum. As I wrote two years ago:

If you did that in every season from 1989 to 2014, your model would have been off by, on average, 2.48 wins per team. This is calculated by taking the absolute value of the difference between 0.500 and each team’s actual winning percentage, and multiplying that result by 16. So that should be the absolute floor for any projection model: you have to come closer than that.

Now, let’s flash back to July of this year. The USA Today published its preseason predictions in a rather provocative fashion, particularly with respect to two teams. I see a ton of preseason projections every year and forget them minutes later, so please forgive me if you feel like I am picking on the USA Today here. That is not the intent, and other publications have made more egregious errors but are not at my fingertips. But this publication picked the Patriots to go 16-0 and the Jets to go 1-15, which was rather extreme.

Upon further view of their predictions, many of them are pretty ugly. So I decided to compare those predictions to the “every team in the same” test, or the “8-8” system.

There were six teams the USA Today got really wrong, where an 8-8 projection would be at least 3.0 games closer to being accurate:

The Buffalo Bills are 8-7 (off of 0.500 by 0.5 wins); the USA Today predicted them to go 4-12 (off by 4.5 wins).

The Green Bay Packers are 7-8 (0.500 projection is off by 0.5); the USA Today predicted them to go 12-4 (off by 4.5).

The Los Angeles Rams are 11-4; an 8-8 projection would be off by 3.5 games, but the USA Today had the Rams are 4-12, off by 7.5 games.

The Oakland Raiders are 6-9 (off by 1.5); the USA Today had them at 11-5 (off by 4.5).

The Detroit Lions are 8-7 (off by 0.5); the USA Today had them at 5-11 (off by 3.5).

The Tennessee Titans are 8-7 (off by 0.5); the USA Today had them at 12-4 (off by 3.5).

You might say the loss of Aaron Rodgers shouldn’t be held against them, and that the Rams success caught everyone off guard. Both of those things are true, but we also know that superstars get hurt and surprise teams happen every year. Both of those facts should urge predictors to be more conservative in the aggregate.

The USA Today thought the Titans would be great and the Bills terrible; both are 8-7. And the USA Today had the Raiders at 11-5 and the Lions at 5-11; instead, Detroit has two more wins than Oakland. These, again, are signs that we shouldn’t be too overconfident in our preseason projections (a look at the Giants and the Rams projected wins totals would also work to that effect).

Now, there were also three teams where the USA Today beat the 8-8 system by at least 3 games.

The Indianapolis Colts were projected to go 5-11 by the USA Today; they are 3-12 (USAT off by 1.5, .500 prediction off by 4.5).

The Cleveland Browns were projected to go 4-12; they are 0-15 (USAT off by 3.5, .500 prediction off by 7.5).

The Pittsburgh Steelers were projected to go 12-4; they are 12-3 (USAT off by 0.5, .500 prediction off by 4.5).

In the case of the Colts, Browns, and Bears, predicting them to be bad — but not terrible — was the wise move. (That would have worked with the Jets, too: the 1-15 projection is now off by 4 or 5 wins, giving another win to the 8-8 system). The Steelers were projected to be very good, and that prediction was nailed. The USA Today even wins the Patriots bet as we stand right now (12-3 is closer to 16-0 than 8-8), but a more conservative approach would have been better.

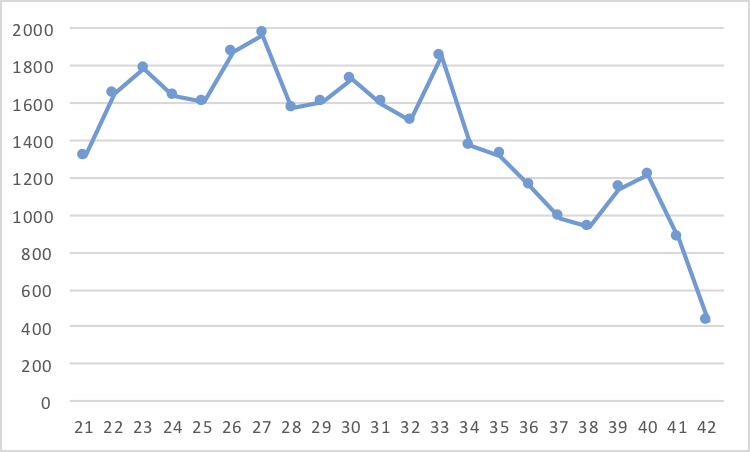

Overall, the USA Today fared worse than the blind 8-8 system. The USA Today projections were closer than the 8-8 system for 13 teams. Meanwhile, the 8-8 system was closer on 15 teams, with four teams (Houston, Kansas City, Jacksonville, New Orleans) currently graded as ties. Take a look: [continue reading…]