Yesterday, I did a fairly simple analysis to compare interception numbers across eras. Because I covered the methodology in the previous post, I am not going to regurgitate that information here. Instead, I want to just get right into it. When I did the career adjusted sacks post, I went step-by-step in the same manner I did in the single season article. This time, however, I think we can skip past all that and look at the end results.

Career Adjusted Interception Totals

The first table is sorted by the last column, but you can re-sort by any header you like. Using Rod Woodson as an example, here’s how you read the table: Woodson intercepted 71 passes against 8401 attempts at a 0.85% rate. His passing environment modifier (Mod) is worth 142%, and the softened version of that (Soft) is worth 121%. Taking the average of his actual interceptions and interceptions per 500 attempts in order to account for volume gives us the Mid adjustment, which is 98% in Woodson’s case. Applying my homebrewed league strength multiplier (LSM) gives him a 99% adjustment.

If we multiply Woodson’s 71 interceptions by Mod, Mid, and LSM, we get a whopping 97.7 adjusted interceptions for his career. If we dampen it by multiplying those 71 picks by Soft, Mid, and LSM, Woodson’s career adjusted interceptions come to 83.2, good for the highest mark ever. [1]For the ModTot, that’s 71 * 142% * 98% * 99%. For the SoftTot, that’s 71 * 121% * 98% * 99%.

Using the actual historical average as a baseline appears to be a bit much, going by the numbers it produces. I think having Charles Woodson, Ed Reed, Rod Woodson, a serial rapist, and Aeneas Williams as the top five (by ModTot) is fine; giving Chuck credit for 101 interceptions is a bit much for me. Moving the all time leader in picks, Paul Krause, down to ninth also feels a tad harsh as well. Sure, I think he tends to be overrated by people who look at one number and base their entire evaluation on that single data point, but I also think having such a commanding lead over any modern player should count for something. For this reason, I think the SoftTot column produces results with greater face validity.

The last column gives us a top ten of seven Hall of Famers, one senior candidate who will likely get the necessary votes soon, possibly the best safety of the 1990s who would be in Canton already if he played for Dallas or San Francisco, and a a vile monster who was good at picking off passes and not really much else.

Let’s Be Reasonable

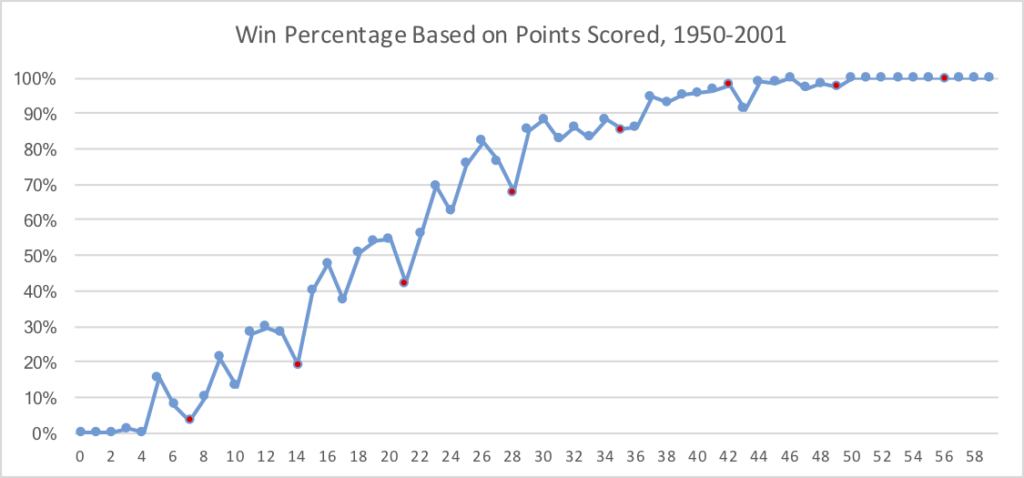

The wacky looking career totals form the table above convinced me to try using a new baseline. I decided to use the last 40 years of football, which incorporates nearly the entire period of open offense football. [2]I refer to football in the wake of the Mel Blount Rule and rules enabling offensive linemen to extend their hands to block in 1978, as well as the subsequent offensive revolution heralded by the … Continue reading When I looked at that timeframe, the historical baseline moved from 4.80% to 3.16%. because of that, I have dubbed the new baseline the Austin Percentage. Having a lower baseline means that fewer players will see their totals go up, and only the most recent players will their totals go up significantly.

The table below is sorted by the last column, but you can sort by any of the headings. Using Krause as our example, read the table thus: Krause picked off 81 passes against 5623 attempts at a 1.44% rate. His volume adjustment is worth 117%, and his league strength multiplier is worth 88%. His Austin figure is 60%, which comes to 80% when the effect is halved. [3]Recall from the first table that his Mod and Soft were 91% and 96% because of the highest baseline. If we apply the Mid, LSM, and Austin modifiers to Krause’s 81 actual interceptions, his total plummets to 49.9, which ranks tenth on the career list. If we replace the Austin modifier with the softened version, Krause’s number falls to just 66.4, which allows him to maintain his place atop the interception mountain. [4]To arrive at the numbers in the Austin column, we use: 81 * 117% * 88% * 60%. To find the results for the HalfTot column, we use: 81 * 117% * 88% * 80%. These figures are rounded and will produce … Continue reading

If you earnestly believe older players relied too much on archaic passing to glean their big interception totals, the Austin column might be for you. Before we find Krause at number ten, only Rod Woodson and Eugene Robinson had any action prior to 1990. Recent ball hawk Richard Sherman is in a fourteen-way tie for 104th place in career interceptions, with 37. However, when Austin 3.16 comes around, Sherman jumps to 18th, which does feel more appropriate for one of the premier turnover artists of recent vintage. In fact, his 8.4 interception boost is the highest number of any player, just beating out the bonuses of 8.3 and 8.1 for fellow playmakers Xavien Howard and Marcus Peters. Wandering mercenary Aqib Talib finds himself pretty high on the career list when looking at the Austin total.

While some recent players saw modest gains, older players saw their totals fall off a cliff with the lower baseline. Emlen Tunnell, a real life hero who picked off 79 passes—but did most of his damage in the 1950s—suffers a reduction of 43.6 from his total. He goes from ranking second on the official list to 54th on the Austin list. That seems a little steep, even to a noted old school player hater like I am. Night Train Lane and Johnny Robinson join Krause and Tunnell as the only other players to lose at least 30 from their totals. Turn-of-the-century players like Sam Madison and Patrick Surtain see almost no change in their career numbers.

I think the last column makes the most sense at first glace. Tunnell, Robinson, and Jim Norton all lose more than 20 from their real numbers, and no one gains more than 3.6. Krause loses 14.6, but because Tunnell lost 22 and his lead over anyone else was huge, he remains in first place. Rod Woodson loses 4.7 from his total, while Charles Woodson and Ed Reed each lose about half a pick, resulting in the three ending pretty clustered, and all close to Krause at the top. While Tunnell has a large reduction, his actual number of interceptions was so high to begin with that he still ranks sixth here.

I am often interested to see where Ken Riley and Dave Brown will fall, relative to one another. Riley has 65 interceptions to Brown’s 62. The Austin adjustment puts Brown ahead, while my preferred adjustment leaves the Bengals legend with a 54.6 to 53.4 lead. Riley never made a Pro Bowl, but he earned first team all pro honors once and second team honors twice. Brown made one Pro Bowl and one all pro second team. Given how close together these two are in terms of actual production, the gap in their public perception is pretty interesting to me. When you consider the fact that Brown was his team’s top corner, while Lemar Parrish was the top corner in Cincinnati until 1977, the issue is further muddled.

I will leave further commentary to the FP faithful, if any remain.

References

| ↑1 | For the ModTot, that’s 71 * 142% * 98% * 99%. For the SoftTot, that’s 71 * 121% * 98% * 99%. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | I refer to football in the wake of the Mel Blount Rule and rules enabling offensive linemen to extend their hands to block in 1978, as well as the subsequent offensive revolution heralded by the likes of Bill Walsh, Don Coryell, and Joe Gibbs. |

| ↑3 | Recall from the first table that his Mod and Soft were 91% and 96% because of the highest baseline. |

| ↑4 | To arrive at the numbers in the Austin column, we use: 81 * 117% * 88% * 60%. To find the results for the HalfTot column, we use: 81 * 117% * 88% * 80%. These figures are rounded and will produce slightly different results if you copy and paste to work with them yourself. |