Yesterday, I began looking at how the 12 expansion teams of the modern era fared during their first 13 years of existence. Today, the bottom half of the list:

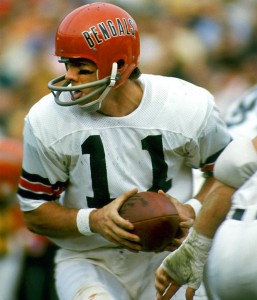

#6 Cincinnati Bengals (1968-1980)

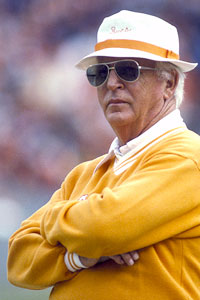

Art Modell purchased the Browns in 1961; Modell and Paul Brown, the only coach the franchise had ever known, clashed almost immediately. In January 1963, Modell fired Brown, who began plotting his revenge almost immediately. At the time, the AFL was gaining traction, but Brown had no desire to be in a “lesser” league. By the time the AFL had decided to add Cincinnati as an expansion franchise, the AFL and NFL had already agreed to merge prior to the start of the 1970 season. Brown was part of the ownership group that brought the Bengals into professional football, and became the team’s first head coach. One of his first decisions? Hiring a young Bill Walsh.

The Bengals played like a typical expansion team in 1968, but their hopes seemed to change the following season. With the 5th pick in the 1969 draft [1]The AFL and NFL had a common draft beginning in 1967; the Bengals, with the second worst record in the league, ended up with only the fifth pick in the draft, causing them to miss out on O.J. Simpson … Continue reading, Brown didn’t have to look far: he selected Cincinnati signal caller Greg Cook. The former Bearcat was an immediate star: his 9.4 yards per attempt average remains the highest ever by a rookie quarterback with at least 175 pass attempts. Cook led the AFL in completion percentage, yards per attempt and quarterback rating, but was mostly known for his powerful arm. His 17.5 yards per completion average that season has only been bested once since, and it remains the 12th highest mark in league history. Making the season more incredible was that Cook tore his rotator cuff against the Chiefs… in week three. Following surgery to repair his shoulder, Cook threw just three more passes, prompting many to wonder how great he could have been.

The Cook injury left the Bengals devoid of talent at the quarterback position. Cincinnati started the 1970 season 1-6, and had turned to a weak-armed but mobile and intelligent quarterback named Virgil Carter to lead the offense. It was Carter and Walsh who implemented the first version of the West Coast Offense into the NFL, and the Bengals won their last seven games to sneak into the playoffs.

In 1971, Carter led the league in completion percentage, but by 1972, Ken Anderson had beaten him out for the job. Anderson would lead the league in completion percentage in ’74, passing yards and yards per attempt in ’74 and ’75, and make the Pro Bowl in ’75 and ’76. Cincinnati, despite being stuck in the same division with football’s emerging dynasty, won at least 10 games in 1973, 1975 and 1976. In 1975 the Bengals went 11-3, with two of those losses coming against the Steelers.

Brown was threatened by the ambitious Walsh, and the rocky relationship between the two climaxed after the ’75 season. Brown, ready to retire, named offensive line coach Bill Johnson his replacement. Walsh resigned, and the team began a steady decline as the decade concluded. Under Forrest Gregg in 1981, the Bengals had a shocking turn around that landed them in the Super Bowl, but that lands just outside the scope of this study. During the Bengals first 13 seasons, the team won no playoff games, but did make the playoffs three times and won 47% of their games. The early Bengals will always be remembered for being at the intersection of the passing of the torch — however unwillingly — between two of the best coaches of all-time.

#5 Houston Texans (2002-2011)

After Dom Capers’ success in guiding the Carolina Panthers into the NFL, Houston’s Bob McNair tapped Capers to try his hand at the expansion game a second time. Unfortunately for the Texans, they were placed in the same division as Peyton Manning, who was about to embark on perhaps the greatest nine-year period of quarterback play in the history of the sport. The Colts would win the division seven of the first nine years of the AFC South’s existence, going 16-2 against the Texans over that stretch. The Colts dominance with Manning was remarkable: I argued in the New York Times last January that Manning’s dominance was the reason Gary Kubiak and Jack Del Rio had been given such unusually long leashes.

The 2002 Texans started in miracle fashion, defeating the Dallas Cowboys in their very first game. But the decision to build the franchise around Capers and quarterback David Carr ended up backfiring. Houston appeared to make steady progress in its first three seasons, before crashing miserably to a 2-14 mark in 2005. Capers was shown the door, but Carr was kept around for one more season. While Carr made modest improvements in ’06 — he actually led the league in completion percentage thanks to an uber conservative playing style — he ultimately will be remembered for having led the league in sacks in 2002, 2003 and 2005. Outside of Andre Johnson, the Texans generally struggled in the draft until being fortunate enough to land Mario Williams with the first overall pick in 2006. Whiffing throughout the draft, and on the quarterback and coach, ultimately had the franchise rebuilding after four years.

Under Kubiak, who was brought in to replace Capers, the Texans steadily improved as an organization. They became a trendy pick for sportswriters to tout seemingly every summer, but Houston consistently missed the playoffs. With Manning injured in 2011 and Wade Phillips doing a masterful job coaching the defense, the Texans finally captured the AFC South last season. Houston won its first playoff game against the Bengals, before losing a heartbreaker in Baltimore a week later.

The Texans struggled as an expansion franchise, essentially repeating the exercise twice. The second time around the Texans got it right, but the slow start relegates them to the bottom of the list. With 3 seasons remaining, it’s too early to truly compare the Texans to any other franchise on the list. Like the Cowboys and Vikings, the Texans appear well positioned in year 10 to begin a run of success, especially in a watered down AFC South. But by winning just 41% of their games to date, it’s hard to rate them any higher than #5.

#4 – Atlanta Falcons (1966-1978)

The Falcons bridge the gap between the mediocre expansion franchises and the truly terrible. Atlanta won 37% of their games during their first thirteen seasons and went through five coaching changes. For awhile, Atlanta was more interesting for what happened before it was awarded a team than for what the Falcons ever did on the field.

In the summer of 1965, the AFL and NFL wars were at their peak; the leagues were still a year away from formally announcing the merger. Both leagues were looking to expand, with the AFL ultimately landing in Miami and Cincinnati while the senior league settled in Atlanta and New Orleans. But in 1965, all of football eyed Atlanta. In the early ’60s, Atlanta was one of the largest growing cities in the country and the most attractive city in the Southeast region. At the time, there weren’t any professional sports teams in any of the seven southeastern states. In 1964, the city nearly acquired the Cardinals from St. Louis, and things looked grim once the Cardinals chose to remain in Missouri. Then, in the fall of 1964, the city was able to lure baseball’s Milwaukee Braves to Atlanta and become the first major pro sports team in the South. In fact, the city of Atlanta had already begun building Atlanta Stadium (renamed Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium in 1976) in the hopes of luring a professional sports franchise. In the middle of 1965, the AFL had reached an agreement with the city to bring professional football to the South. The NFL, fearful of losing a key market to the AFL, swooped in at the last minute, reaching an agreement with the city to give the NFL exclusive rights to Atlanta. The AFL responded by going to Miami.

Atlanta nailed its first pick, Texans linebacker Tommy Nobis, but did little right in their first decade. With the last pick in the first round of the ’66 draft, Atlanta selected quarterback Randy Johnson from Texas A&M-Kingsville. Johnson played poorly as a rookie and then regressed each of the next two seasons. Norb Hecker, an assistant in Green Bay under Vince Lombardi, was tapped to be the franchise’s first coach. Hecker won three titles in Green Bay and would pick up four more rings with the ’49ers in the ’80s. As the head man in Atlanta, however, he went 4-26-1. Norm Van Brocklin — after having failed as the inaugural coach in Minnesota — replaced Hecker and had mixed results as coach of the Falcons. Bob Berry, who had been drafted by Van Brocklin in Minnesota, became the new quarterback, and posted very good numbers in five years with the Falcons. But injuries to Berry and below-average talent kept the Falcons from ever topping 7 wins in a season.

After ’72, Atlanta traded Berry back to Minnesota for quarterback Bob Lee, who led the Falcons to a 9-5 mark in his first season. But the team regressed over the next three years, going 3-11, 4-10 and 4-10 in the middle of the ’70s. It wasn’t until Atlanta hired Eddie LeBaron as general manager and Leeman Bennett as head coach that the Falcons finally turned things around. Bennett, along with Jerry Glanville, helped give the franchise their first identity: in 1977, Atlanta set the record for fewest points per game allowed in a season, a mark that still stands. The “Gritz Blitz” Falcons only went 7-7, losing five games when the Falcons scored seven or fewer points. The next year — the 13th season for the franchise — Atlanta won 9 games and made the playoffs for the first time.

Because they only won 37% of their games, it’s hard to put Atlanta any higher than #4. The Falcons went through 5 head coaches and 13 different starting quarterbacks in their first 13 seasons, struggling to find an identity for over a decade.

#3 – Tampa Bay Buccaneers (1976-1988)

The Buccaneers famously started off as a franchise by losing their first 26 games. In year three, coach John McKay hired Joe Gibbs to run the offense, and drafted Grambling State’s Doug Williams in the first round. The defense, then led by Tom Bass, had started to become one of the league’s best units. Led by Lee Roy Selmon and a strong group of linebackers, the Bucs led the league in yards per carry allowed in 1978 and finished 5-11. In 1979, the Buccaneers ranked 1st in both points and yards allowed, and took an 8-7 record into the final week of the regular season. A victory would clinch the NFC Central division; a loss would keep Tampa Bay out of the playoffs. Playing in monsoon conditions, Ricky Bell rushed 39 times for 137 yards, and Tampa Bay kicked a fourth quarter field goal to win, 3-0. McKay’s squad reached the NFC title game, but fell to the Rams, 9-0.

Tampa Bay again made the playoffs in ’81 and ’82, but were one-and-done both times, courtesy of the Cowboys. Tampa plummeted to 2-14 in 1983; in 1984, the Bucs went 6-10, revovling the offense around James Wilder (407 carries, 85 receptions) and little else. In 1985, Atlanta’s Leeman Bennett took over as head coach and Steve Young, via the USFL, became the new quarterback. But neither would achieve any success in Tampa Bay: Bennett went 2-14 in consecutive years, while Young was unable to accomplish much with a depleted roster. The Buccaneers, even with consecutive #1 picks, were unable to fix the roster. Tampa Bay selected Bo Jackson with the first pick in 1986, but cost him his college eligibility by taking him on a private plane and forced him to choose baseball or football: he chose the former. In ’87, Tampa went with Vinny Testaverde, who was unable to do much more than Young had done the prior two years.

From 1976 to 1988, Tampa won only 29% of their games, the worst mark on the list. During that time, they had one of the most influential owners in the sport in Hugh Culverhouse, who would be much more relevant than his team during his tenure. (You can read about Culverhouse in Denis Crwaford’s excellent book here.) But with three playoff appearances in four years, the Bucs at least gave their fans one good stretch of football and a couple of home playoff wins: that’s more than you can say about the last two teams on the list.

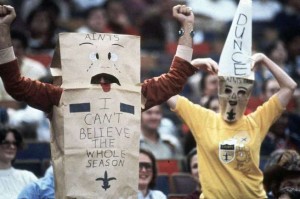

#2 – New Orleans Saints (1967-1979)

You can sum up the first two decades of New Orleans football with two words: The ‘Aints. It wasn’t until season twenty-one that the Saints finally made the playoffs or had a winning record; it took thirteen years for the team to even reach .500. New Orleans went through six head coaches in that span, and won just 30% of their games.

The Saints knew the value of a quarterback, and spared no cost in trying to find the man to build the franchise around. New Orleans traded the first overall pick and Bill Curry (acquired in the expansion draft) to the Baltimore Colts for Johnny Unitas’ backup, Gary Cuozzo. Curry would play in Baltimore for six years and make two Pro Bowls at center. Baltimore used the first pick to draft Michigan State’s Bubba Smith, and the two would help the Colts reach Super Bowl III and win Super Bowl V.

It was the first of many bad trades for the franchise. Cuozzo had become a hot commodity by throwing five touchdowns in relief of Unitas in his first NFL start, and the legend continued to grow from there about his abilities. But Cuozzo was a horrible fit for the expansion Saints. Behind a miserable offensive line, former San Francisco quarterback Billy Kilmer — who had also played halfback for the 49ers — was a better fit for New Orleans. Both men played in 1967 as the Saints struggled to a 3-11 season.

Hank Stram was hired in 1976 to turn the team around, but he could not work his magic in the Bayou. Archie Manning would miss the entire season with a shoulder injury, leaving the offense in the hands of Bobby Douglass and Bobby Scott. Even with Manning back in ’77, the Saints could only win 7 games in two years under Stram.

Finally, though, things looked bright in New Orleans as Dick Nolan was hired. In ’78, the team went 7-9, and got up to 8-8 in their thirteenth season. Manning was playing at a Pro Bowl level and Chuck Muncie was able to deliver on his enormous potential. It would all unravel soon, of course, but that’s outside the scope of this study. After thirteen years, it at least looked like the Saints had finally gotten on the right track.

#1 – Cleveland Browns (1999 to 2011)

How do you beat out the Saints for worst expansion franchise? The Browns had slightly more success on the field than the Saints, going 68-140-0 compared to New Orleans’ 54-127-5. And the Browns did make the playoffs in 2002, although it’s worth noting that they finished 9-7, a record that eight other AFC teams matched or exceeded that season. But considering how much easier it is in the era of free agency to turn around a franchise, the ineptitude of the Browns is even more confounding.

Consider that sixteen different quarterbacks have started a game for Cleveland since 1999. The Browns have gone from Tim Couch to Kelly Holcomb to Jeff Garcia to Trent Dilfer to Charlie Frye to Derek Anderson to Brady Quinn to Jake Delhomme to Colt McCoy, among others, in an attempt to find a reliable quarterback. Even the Saints were able to solve that part of the equation. The Browns have had six different coaches since re-entering the league, and a seventh coaching hire may not be far behind. Cleveland hasn’t had any sustained period of success, or anything longer than a fleeting moment when things looked appeared to be going in the right direction.

Cleveland started with Chris Palmer, who had been instrumental in directing the Jacksonville offense in ’97 and ’98. With their first pick, Cleveland took Tim Couch, a Mike Leach quarterback before NFL teams knew exactly what that meant. Cleveland lost their first game 43-0 to the rival Steelers, and finished the season 2-14. Cleveland went 3-13 the following year, ranking last in points scored and points differential for the second year in a row. Defensive end Courtney Brown, a star at Penn State with limited bust potential, ended up being the Browns’ second straight bust with the number one pick.

Cleveland fired Palmer and chose one of the brightest stars in college football, Miami’s Butch Davis, to resurrect the franchise. It would not be an exaggeration to state that Davis had better high-end talent in college, as Clinton Portis, Santana Moss, Reggie Wayne and Jeremy Shockey were on the 2000 Hurricanes offense; the defense featured Ed Reed, Vince Wilfork, Phillip Buchanon, Jonathan Vilma and Antrel Rolle. Butch Davis managed to find a needle in a haystack: the one Hurricane he spent an early pick on in his first three years was running back James Jackson, who averaged just 3.3 yards per carry on 321 carries in Cleveland.

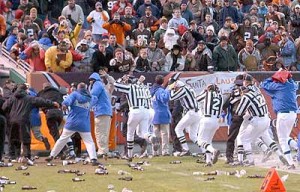

Davis’ Browns improved to 7-9 in his first season, largely on the strength of a strong defense. The best player on the team was Jamir Miller, a linebacker who would be the only Browns Pro Bowler until 2007. Miller tore his Achilles tendon in pre-season the next year, and never played again in the NFL. The ’01 season will mostly be remembered for Bottlegate, as Browns fans bitterly littered the field with beer bottles following a blown call.

The next season was the “highlight” for the new Browns, as Cleveland went 9-7 and squeaked into the playoffs. But it arguably caused more harm than good: in the playoff loss to Pittsburgh, Kelly Holcomb played magnificently, essentially signaling the end of the Tim Couch era. Holcomb started 10 games for the Browns after that, going 3-10. From ’03 to ’05, Cleveland won just 15 games, and looked no closer to having any direction or identity than they had before they ever re-took the field.

By January of 2005, ex-Browns coach Bill Belichick had become king of the coaching universe, an additional grain of salt to be rubbed in Cleveland’s wounds. The Browns responded by going after Belichick disciples, first with Romeo Crennel, then with Eric Mangini, in the hopes of hiring Belichick by osmosis.

In Crennel’s first year, Cleveland ranked last in points scored. The next year, Cleveland ranked in the bottom three in points and yards, struggling to a 4-12 record. In the 2007 off-season, Cleveland staged a quarterback competition between Charlie Frye and Derek Anderson — and drafted quarterback of the future Brady Quinn. The battle was hotly contested through training camp and then pre-season; Crennel famously flipped a coin to see who would start the first pre-season game. On September 3rd, Crennel announced that he was going with Charlie Frye as his week one starter. Frye didn’t even make it to half-time, getting benched by Crennel in favor of Anderson.

In a season that would do little more than prolong the agony and uncertainty, Anderson ended up having a Pro Bowl year, although Cleveland ultimately could not secure a playoff berth. With Anderson, Jamal Lewis, Kellen Winslow, Jr., and Braylon Edwards, the Browns looked to have the pieces for a dynamic offense for years to come. But greatness was not in the cards for the Browns. The next year, Winslow would develop a staph infection — one of at least six Browns to do so in a four-year period — and would catch only three more touchdowns in a Browns uniform. Braylon Edwards and Derek Anderson both flopped in 2008, and father time finally caught up with Lewis. The ’08 Browns stumbled to 4-12, setting the stage for the next Belichick disciple to come to town.

Under Mangini, the Browns went 5-11 in both 2009 and 2010, and could not decide on a quarterback. First it was Brady Quinn, then Derek Anderson, then Quinn, then Anderson, and for a moment or two, Josh Cribbs. Clevleand drafted Colt McCoy in 2010, but none of McCoy, Jake Delhomme or Seneca Wallace would win more than two games that season. In 2011 the Browns, now under Pat Shurmur, went all in on McCoy; the result was a 4-12 season and the impetus to draft Brandon Weeden in the first round of April’s draft.

With countless regime and quarterback changes, no organization has looked this inept and lacked an identity over the past thirteen years like the Cleveland Browns. From ’67 to ’79, in addition to the Saints, the Giants didn’t make the playoffs during that stretch, and the Falcons, Bills, Lions and Chargers only made it once. From 1999 to 2011, every team made the playoffs, and only the Bills joined Cleveland with an 0-1 record. Considering the era of free agency, no franchise has had a less impressive first thirteen years than the new Cleveland Browns.

Of course that’s just my opinion. You can vote in the poll below:

[poll id=”3″]

References

| ↑1 | The AFL and NFL had a common draft beginning in 1967; the Bengals, with the second worst record in the league, ended up with only the fifth pick in the draft, causing them to miss out on O.J. Simpson and Joe Greene. |

|---|