Last year, Jimmy Graham broke Kellen Winslow’s record for receiving yards in a single season by a tight end. Winslow gained 1,290 yards as a second-year player in 1980 for the San Diego Chargers. Last year, Graham finished with 1,310 receiving yards in his second season, while also catching 99 passes and scoring 11 touchdowns. Graham broke Winslow’s 31-year-old record, but Graham was leapfrogged in about fifteen minutes. By the end of the last Sunday of the regular season, Rob Gronkowski had upped his total to 1,327 yards, making him the new single-season leader in receiving yards and receiving touchdowns by a tight end.

Jason Witten and Aaron Hernandez each topped 900 receiving yards in 2011, and Tony Gonzalez, Antonio Gates and Vernon Davis remain among the game’s elite at the position. It would not be difficult to argue that we’re in a golden age of tight ends. There’s no doubt that passing has increased in both quantity and quality; have tight ends been the biggest beneficiaries of that change?

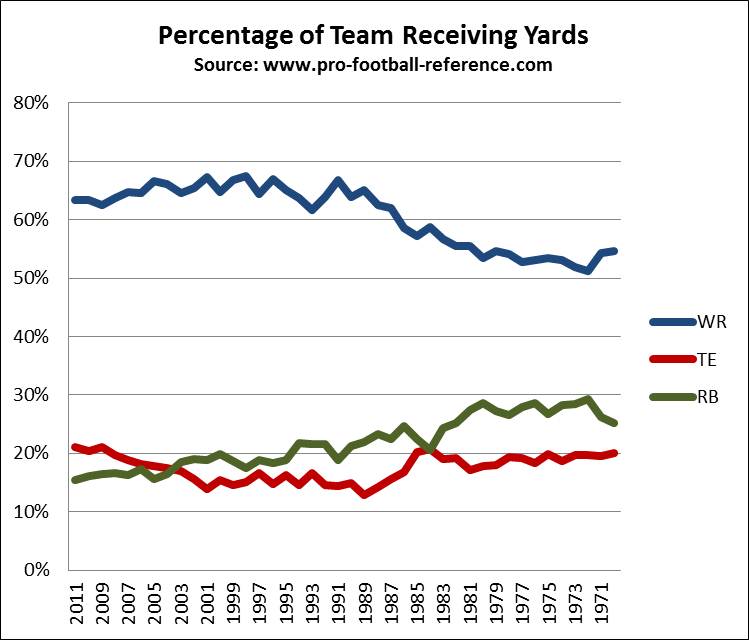

I examined every season in the NFL since 1970, when the AFL and NFL merged. I then calculated the percentage of receiving yards for each team that went to its running backs, tight ends and wide receivers. The table below shows those results[1]Some caveats: Obviously many players straddle the line across multiple positions. There are some judgment calls involved with H-Backs, tight ends turned wide receivers, running backs turned tight … Continue reading.

By the late ’90s, tight end production had dropped by about 25% of where it was at in the first years following the merger; running back contributions in the passing game had fallen even further, to about two-thirds of their previous levels. Wide receivers had become even more strongly the focus of the quarterback’s eye, as teams started using three- and four-wide receiver sets with regularity.

But as you can see, tight ends have regained their relevance in the last decade, stealing yards from both running backs and wide receivers. Tight end production was relatively high in the early days of the post-merger period, also known as the modern nadir of passing in general. Teams rarely used three wide receiver sets, and a fullback was a mainstay on the field. As a result, even if the tight end of the ’70s wasn’t necessarily as skilled a receiver as some of today’s stars, he was competing with a fullback instead of a slot receiver for his quarterback’s attention. As the fullback began being phased out, teams threw increasingly more often to wide receivers. By the end of the ’90s, the average team’s WR3 was responsible for roughly the same amount of receiving yards as the team’s top tight end or top receiving running back, representing a significant departure from prior history.

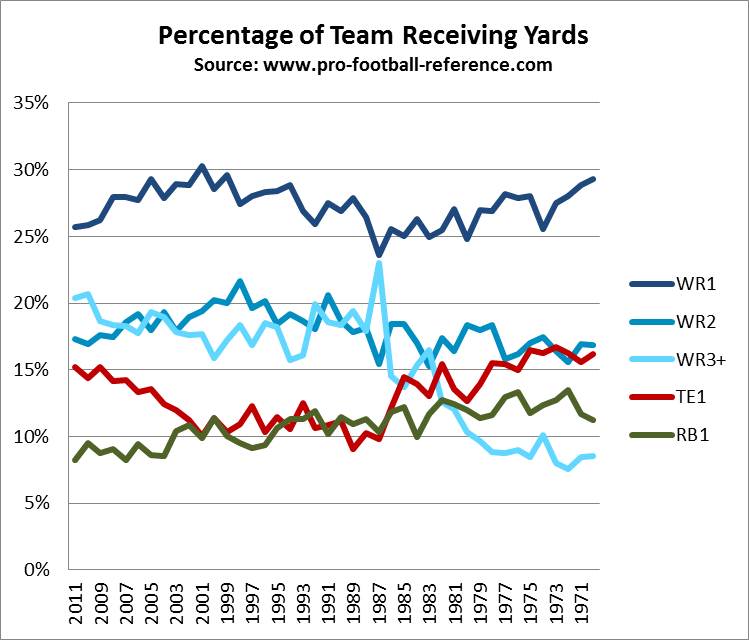

That’s a helpful overview, I hope, but we need to get more specific. The chart below shows the average production for each team’s number one and number two receivers, number one tight end, number one running back, and the production of all other remaining wide receivers on the team.

This is a fascinating graph to decipher. Some thoughts [2]For those wondering what the spike is in the middle of the graph on the WR3+ line, don’t pay it much attention. That spike is for the 1987 season, and due entirely to the use of replacement … Continue reading:

- The value of a WR1 has been relatively consistent over this time frame. I think most of the ups and downs are probably due to sample size issues rather than changes in league philosophy. However, I’d argue that we may be in a period where the value of a “true” WR1 who can dominate on the outside is declining; three good wide receivers are probably more valuable than the Larry Fitzgerald model the Cardinals have been trotting out the last two years. Arizona, in fact, decided to rectify the situation by drafting Notre Dame’s Michael Floyd in the first round of April’s draft. Consider that two of the three leading receivers in the NFL last season, Victor Cruz and Wes Welker, gained the lion’s share of their production come while lined up in the slot [3]According to Pro Football Focus, Welker (1,203 yards) and Cruz (1,208) both recorded the vast majority of their receiving yards while playing inside..

- A team’s second wide receiver can be expected to produce about 16-20% of the team’s total receiving yards, a mark that has been steady over the past four decades. But what’s been even more consistent is that the average WR2 and TE1 have combined for just over 30% of a team’s receiving yards. As the TE1 becomes a better target, it’s natural to expect the WR2 to be one of the sources to give up targets. It’s reasonable to conclude that the small spike in the WR2 line in the late ’90s is strongly related to the similar decline for TE1 production over those same years.

- There were two key rules changes enacted in 1978. The first prohibited bumping, chucking, or otherwise making anything other than incidental contact with a receiver beyond five yards from the line of scrimmage. The second allowed offensive lineman to be able to extend their arms, and push with open hands, allowing for better blocking and fewer holding penalties. With those rules in place, quarterbacks needed fewer blockers and receivers needed to be less skilled to get open. As a result, three and four wide receiver sets become more common, and the fullback was phased out. You can see the huge spike in the value of the third, fourth, fifth and so on wide receivers in the chart above. From 1970 to 1977, non-starting wide receivers consistently produced just under 10% of the team’s total receiving yards; by 1990, that number had doubled, and has shown no signs of subsiding.

- Whose slice of the pie did the third and fourth receivers take? The short answer is, the running backs. Running backs outside of the team’s top receiving back consistently gained about 15% of the team’s yards in the early ’70s; that number has been cut in half in today’s NFL. A team’s RB1 (again, measured by receiving yards only) has also lost a few percentage points since the 1970s. Fullbacks like the Jets’ Clark Gaines (17 receptions in a 1980 game) have been replaced by players like Wes Welker. Last year, over at smartfootball, I noted that the ’77 Colts had two running backs, Lydell Mitchell and Don McCauley, lead the team in receptions. Two running backs simply aren’t on the field at the same time very often in today’s game. Of course, that’s still a separate issue from why the RB1 production has been declining. I have some thoughts, but I’m curious to hear what you guys think on that one.

- And what of the tight end? Putting aside a team’s top tight end, the other tight ends have seen a small spike, going from about three to four percent to six percent of a team’s total yards. That reflects the fact that now teams frequently have multiple tight ends that are legitimate receivers, with the Patriots obviously leading the way. The TE1 spot has obviously shot up in importance since the ’90s, when you typically saw the top tight end just getting north of ten percent of the team’s yards. But on a percentage basis, TE1s were slightly more productive in the early ’70s. So what gives?

Obviously overall passing yards are up — teams are averaging 220 passing yards per game, not 150, as they did in the early ’70s. So obviously tight end production is up overall, even if the percentage is slightly down. I think the most likely explanation is the most obvious: there are simply more mouths to feed in the modern NFL.

The top tight ends of the early ’70s bore some resemblance to today’s top stars: they played on good offenses with very good quarterbacks and were the team’s first or second weapon. Think of stars like Charle Young in Philadelphia with Roman Gabriel, Ted Kwalick in San Francisco with John Brodie, the Jets’ Rich Caster with Joe Namath, or Jim Hart and Jackie Smith in St. Louis.

But the best offensive teams simply have more weapons today. Rob Gronkowski has to fight with Wes Welker, Aaron Hernandez, Deion Branch and now Brandon Lloyd. Jimmy Graham is great, but Marques Colston, Darren Sproles, Lance Moore Robert Meachem (or this year, Nick Toon) and Devery Henderson gave Drew Brees more than enough options if Graham was covered. Vernon Davis now has four former first round picks at wide receiver on his own team — Randy Moss, Michael Crabtree, A.J. Jenkins and Ted Ginn, along with Mario Manningham and Frank Gore. What would Jermichael Finley do if he wasn’t playing with Greg Jennings, Jordy Nelson, James Jones, Donald Driver and Randall Cobb?

The teams with the best offenses and the best quarterbacks tend to put as many receivers and tight ends on the field as they can. So while Gronkowski and Graham are producing historically great numbers, they’re competing with more quality players than their forefathers had to. But a rising tide lifts all ships, and I don’t think there’s any reason to expect tight end production to decline anytime soon. As good as Graham was last year, he only accounted for 24% of the Saints receiving yards. For an elite tight end, there’s nothing unusual about that.

References

| ↑1 | Some caveats: Obviously many players straddle the line across multiple positions. There are some judgment calls involved with H-Backs, tight ends turned wide receivers, running backs turned tight ends, etc. I did my best to make the appropriate call in each case. Note also that for this article, I’ve eliminated all players who ended the season with negative receiving yards, and am only looking at receiving yards by running backs (which includes fullbacks), receivers and tight ends. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For those wondering what the spike is in the middle of the graph on the WR3+ line, don’t pay it much attention. That spike is for the 1987 season, and due entirely to the use of replacement players for three games. |

| ↑3 | According to Pro Football Focus, Welker (1,203 yards) and Cruz (1,208) both recorded the vast majority of their receiving yards while playing inside. |