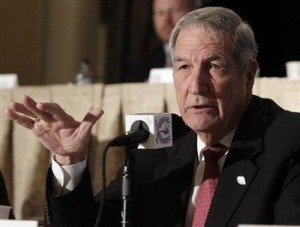

Gene Stallings coached in the NFL in the late ’80s, in between the Jim Hanifan and Joe Bugel eras of Cardinals football. He was the man who led the team as the franchise relocated from St. Louis to Phoenix. He coached under Tom Landry for over a decade in Dallas. But Gene Stallings will always be remembered for working under Bear Bryant and for embodying what it meant to coach Alabama football.

Stallings played on Bryant’s famous Junction Boys team at Texas A&M, and coached under Bryant when the Crimson Tide won national championships in ’61 and ’64. After his failed stint in the NFL, Stallings returned to Alabama, this time as the head coach. His crowning achievement was winning the 1992 national championship, capping a 13-0 season.

So why the background on Stallings today? One of the fun things about owning a website is seeing where your traffic comes from. I noticed a bunch of hits were coming from RollBamaRoll.com. So I went to the site to see what was driving the traffic (as it turns out, a random link to this passer rating article) and I found this great quote by Stallings on another page:

Everyone keeps talking about our game with Miami [in the 1993 Sugar Bowl]. The reason we won against Miami is this: We had the ball 15 minutes more than they did. We ran the ball for 275 yards against Miami. They ran the ball for less than 50 yards. When the game was over, we won. After a game, it may not look good. The alumni may be asking why we are not entertaining them. Let me assure you that our job is to win football games. You win football games by running the ball, stopping the run and being on the plus side of giveaway-takeaways.

I think every coach [1]Mike Martz excluded, of course. at every level has, at some point, uttered a phrase to essentially the same effect. It is quintessential Alabama football, but it could have just as easily come out of the mouth of Greasy Neale or Bill Cowher or Vince Lombardi. Of course, whenever I read a quote like that, two immediate questions come to mind. Is it true? And how can I determine if it’s true?

Stallings’ statement is undeniably true in the sense that outrushing your opponent and winning the turnover battle are highly correlated with winning. But as readers of my passer rating article know, such correlation says nothing about which way the causation arrow, if any, points. Take a step back and re-read his quote: It is only a step removed from saying “You win football games by outscoring the other team.” [2]A conservative coach could never utter such words, of course. But perhaps “You win football games by allowing fewer points than the other team” would have caught on if Bear Bryant had … Continue reading In fact, what exactly is Stallings saying besides “You win football games by playing better than the other team?” What is left out in his statement?

Obviously Stallings could never have meant to imply that special teams are meaningless; he surely received his first whistle in exchange for swearing to uphold forever the importance of special teams. And in no way would any coach worth his salt ever say that committing penalties is irrelevant. So if we say turnovers, rushing offense and rushing defense are the keys to victory, and we’re trying to say something more than “outscoring/outplaying the opponent is the key to success,” then we’re left with, essentially, “the passing game isn’t that important.”

But is that true? Gross passing yards probably are unimportant, as Alex Smith argued. But passing efficiency? Perhaps what Stallings really should have said was “winning the turnover battle and the passing efficiency battle are the keys to winning?”

Since 1940, over 10,000 teams have won the turnover battle in a professional football game; 78% of the time, they also won the war. Teams that had one more takeaway than giveaway won 66% of the their games; upping the turnover margin to +2 brings a team’s odds to 80%, and raising it to +3 jumps you to 87%. [3]No team has ever lost a game when winning the turnover battle by 8, 9, or 10 turnovers, but three teams did manage to lose despite a +7 edge in turnovers: the ’83 Bucs, ’67 Bears, and … Continue reading Let’s dig a little bit deeper.

Teams that are +2 in turnover margin *and* win the rushing battle win 91.1% of all games. This would seem to directly support what Stallings is saying. But wait: teams that are +2 in the turnover margin *and* win the passing battle win 93.7% of games. What’s the passing battle? You could define it in several ways — with passing yards obviously not being one of them — but I’m using Net Yards per Attempt to measure each team, which is simply the amount of passing yards by the team (which deducts sack yardage) divided by their total number of pass attempts (including sacks). The more efficient passing teams, i.e., those teams who averaged more NY/A than their opponents, have been even better than the more productive running teams. [4]And for those curious, teams that won the passing and rushing battles, while being +2 in turnovers, won 98% of their games.

At +3 and positive in the rushing margin category, teams won 94.4% of the time; at +3 and positive in the pass efficiency category, teams are successful 96.8% of the time. Teams that force one more turnover than they give up and outrush their opponents have won 84.3% of their games since 1940. But teams were successful 86.9% of the time when finishing +1 and ahead in NY/A differential.

If forced to choose, Tim Tebow prays that his team excels at NY/A differential rather than rushing differential.

Winning the turnover battle is highly correlated with winning — again, understanding that the causation arrow runs in both directions — but throughout the history of professional football, winning the turnover battle and being the better passing team has been better than winning the turnover battle and outrushing your opponent.

But let’s take it a step further and look at games where one team outrushed the other but also lost the passing battle. Those teams won 83.4% (when +3 in the turnover department), 77.0% (+2) and 63.3% (+1) of all games. On the other hand, when teams were outrushed by their opponent but won the NY/A battle, they had winning percentages of 90.7% (+3), 83.9% (+2) and 69.7% (+1). Assuming you can only win one, the evidence is clear: on average, winning the NY/A battle is more important than outrushing your opponent.

And, as you probably expected, the effect is getting stronger. Since 2004, when the NFL began another round of implementation to help the passing game, teams have won 95.7% (+3), 84.4% (+2) and 73.3% (+1) of the time when winning the NY/A battle but getting outrushed. [5]The associated sample sizes are 47 games (+3), 96 games (+2), and 131 games (+1).

Stallings is right, of course, that winning the turnover battle and outrushing your opponents are keys to victory. It should go without saying that game strategy is different when you have an excellent defense and rushing game and are significantly more talented than most of your opponents, as is often the case for Alabama during Stallings’ time and now. I’m taking Stallings’ statement out of context by applying it to the pro game, and that means there are all sorts of caveats that I’m putting to the side for now. If you wanted to take his statement and put in in the mouth of an NFL coach, what you’d want him to say — at least based on the last 70+ years of professional football — is that you win football games by passing efficiently, stopping your opponent from passing efficiently, and being on the plus side of giveaway-takeaways.

References

| ↑1 | Mike Martz excluded, of course. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A conservative coach could never utter such words, of course. But perhaps “You win football games by allowing fewer points than the other team” would have caught on if Bear Bryant had said it. |

| ↑3 | No team has ever lost a game when winning the turnover battle by 8, 9, or 10 turnovers, but three teams did manage to lose despite a +7 edge in turnovers: the ’83 Bucs, ’67 Bears, and ’61 Vikings (click on the links for the boxscores). |

| ↑4 | And for those curious, teams that won the passing and rushing battles, while being +2 in turnovers, won 98% of their games. |

| ↑5 | The associated sample sizes are 47 games (+3), 96 games (+2), and 131 games (+1). |