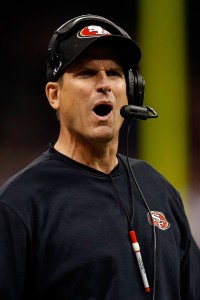

“He’s the best coach in football right now.”

That was what John Harbaugh said about his little brother after the game. It’s hard to argue: I’ve said a few times that I think Jim Harbaugh is the best coach in the league, too. (Although I gave my mythical COTY vote to Pete Carroll.)

It was a classy thing to say by the winning coach, especially on a day where he outcoached his little brother. Actually, the more accurate way of putting it would be to say that “John Harbaugh made fewer bad decisions than Jim Harbaugh.” Let’s go through the game in chronological order

The First Snap

I’ve watched enough Jets games to know that there’s a certain level of horribleness that comes with having a pre-snap penalty at the start of a quarter or half. Maybe you don’t want to blame Jim Harbaugh for the 49ers lining up in an illegal formation on the first snap of the game, but let’s just say this: that’s not how the New York media would react if Rex Ryan’s team did that. Jim Harbaugh would be the first to tell you that it was inexcusable to have such a penalty on the first snap of the game, and the team didn’t look any more prepared on snap two, when Colin Kaepernick and Frank Gore were on the wrong page of a fake-handoff that instead went to Lennay Kekua.

The Fake Field Goal

I’m not going to credit John Harbaugh for this one, but I’m not going to say it was a terrible decision, either. It was pretty obvious that John Harbaugh was going to do something on special teams, and the former special teams coach did have a couple of shining moments (most notably, Jacoby Jones’ 108-yard kickoff return for a touchdown). That said, on this particular play, I disagreed with the call based on the length Justin Tucker had to go to get the first down. I like fake field goals as much as the next guy, but a 4th-and-9 run by your placekicker is asking for trouble.

If I have to blame Harbaugh for a bad mistake on the fake field goal, I’m not going to focus on what he did in the Super Bowl. Think back to November 11th: leading 41-17 with 5:44 left in the 3rd quarter against the Raiders, John Harbaugh called for a fake field goal on the Oakland seven-yard line. Sam Koch ran it in for a touchdown, leaving the Ravens to go for their second favorite fake in Super Bowl XLVII.

But the call wasn’t a terrible one, and being aggressive is wise especially when you’re the underdog. I don’t know what the likelihood of success on that play was — can anyone really estimate that? — but according to Brian Burke, the Ravens needed a 62% chance of it to be successful for it to be the right call based on the Win Probability at the time, although that figure drops to 39% if you instead look at expected points added, instead. The reason the breakeven point is so low because a failure would still ensure that the 49ers would be pinned deep in their own territory. That turned out to be important: San Francisco went three-and-out, and Baltimore got the ball back on their 44-yard line. Three plays later, Joe Flacco hit Jacoby Jones for a 56-yard touchdown. In my opinion, the worse call during that stretch was made by Jim: after the fake field goal was stopped, the 49ers ran two plays and gained no yards. Then, on 3rd and 10, the 49ers ran Frank Gore up the middle. That’s an ultra-conservative call that cost his team more in expected points than John’s fake did.

How Not to Understand Two Point Conversions, by Jim Harbaugh

Trailing 28-6 halfway through the third quarter, Colin Kaepernick hit Michael Crabtree for a 31-yard touchdown. When you’re down by 22 points and score a touchdown, you always go for two. There are a few things to discuss here, so let me take them in order.

1) The two-point conversion rate is roughly 50%. In a world where the rate is say, 40%, the idea of it being “too early” to go for two has real meaning. In Brian Burke-speak, you would only want to go for two when the gain in Win Probability is positive, because the Expected Points Added will always be negative (i.e., it will always be 0.8 vs. 0.99 or 1 for the extra point). So you need to wait until late in the game when you are willing to trade expected value for variance, like say, when you’re trailing by 8 and you score a touchdown.

In a world where the conversion rate is 50%, the expected values between going for two and kicking the extra point are equal to each other. Therefore, the idea of it being “too early” to go for two simply has no meaning. Now there are times when it’s wrong to go for two — say, after being up by two points late in the game and you score a touchdown — but that is based on Win Probability, not on a phrase that has no meaning.

2) Let’s assume that the 49ers had a 50% chance of succeeding on the two-point conversion.Trailing by 22 points before scoring a touchdown, and assuming the 49ers scored two more touchdowns (without that assumption, everything else is meaningless), they would have had a 50% chance of tying the game if they wait until the third touchdown to go for two. But had they gone for two on the first touchdown, San Francisco would have had a 62.% chance of tying the game (with the other two touchdowns). That’s because you can tie the game if you hit on the two-point conversion attempt when down 16, or you can hit on the two-point conversion attempt when down by 16 and when down by 8. There is only a 25% chance of that happening, of course, but it’s a whole lot better than the 0% chance you’re left with in the first scenario. As it turned out, this theoretical exercise in arithmetic turned out to be a pretty big deal. Had Jim gone for two immediately, there’s a 25% chance the 49ers would have only needed a field goal to tie on the final drive instead of the touchdown. [1]I’ll point out that there’s probably some benefit to this bad coaching, as it incentivized the 49ers to go for a touchdown on the final drive instead of playing for overtime. But I feel … Continue reading

Am I thinking like a math nerd instead of an NFL coach? On Thanksgiving this year, Jason Garrett saw the same thing when his Cowboys trailed 35-13 early in the 4th quarter. After a 10-yard pass to Felix Jones to cut the lead to 16, he went for two, and Tony Romo ran up the middle for the conversion. Trailing 28-6 with over 8 minutes left in the third quarter, Peyton Manning once threw a touchdown to Marvin Harrison and then came back and hit Ken Dilger for a two-point conversion to cut the lead to 14. In 2006, Jeff Fisher’s Titans trailed by that same 28-6 score in the third quarter when they scored a touchdown. Fisher went for two and got it. But maybe that’s not a fair comparison since he had the benefit of a mobile quarterback like Vince Young, who scored on a quarterback draw.

3) Harbaugh’s failure to go for two was a tangible error that we can quantify — he cost the 49ers a 12.5% chance of tying the game via the two-point conversion route (and a 25% chance to rectify the situation following the miss). But when trailing by 15, Harbaugh again sent in David Akers to kick the extra point. This error was not as egregious, but trailing by 15 points, you want to go for two in a world where you can convert 50% of the time. This becomes more serious later in the game, but in any event, you always want to know where you stand. Delaying the decision to go for two is akin to putting your head in the sand. Some people might think that Harbaugh didn’t go for two after the first and second touchdowns because he didn’t want to stop his team’s momentum or sap their emotion after scoring. I have no desire to argue with those people.

4) Eventually, the 49ers did in fact score a third touchdown to narrow the gap to two points. I won’t harp too much on the actual play, but was passing really the best option? On 71 rushing plays on two-point conversions from 2007 to 2011, teams converted 46 times (65%). Considering the fact that San Francisco is arguably the best rushing team in the league, this was an odd call. Why did I use data from just 2007 to 2011? Because that post was from early in the year, not because I’m hiding anything. In fact, two-point conversion attempt runs were successful 8 out of 10 times in 2012, [2]I am excluding Matt Bosher’s “run” play, which was the result of a bad snap and not an actual (or intentional) two-point conversion attempt. For the same reason, I am excluding Adam … Continue reading with Maurice Jones-Drew and Colt McCoy being the only exceptions. I have to think San Francisco’s odds were better than 50/50 if they ran it on the two point conversion (which means they likely had a better than 25% chance of converting two straight two-point conversions, maximizing Harbaugh’s earlier error).

Jim the Aggressor

In one of my Super Bowl previews, I noted that Jim Harbaugh was the more aggressive brother when it came to situations other than 4th-and-1. Unfortunately, Harbaugh was not aggressive enough in a key situation on Sunday. Trailing 28-20, the 49ers faced 4th-and-7 from the Baltimore 21. They sent on David Akers for the kick, but after the miss, Chykie Brown was penalized for running into the kicker. Aha! New life for the 49ers! Faced with 4th and 2 from the Baltimore 16, obviously Harbaugh the Younger would go for it, I assumed.But meekly, he did not. If you assume that the 49ers had at least a 50% chance of converting on a two-point conversion, the odds rise a bit when they need two yards but aren’t bunched in on the goal line. Brian Burke has the success rate at 59%, but that’s for an average team.

In any event, forget about the actual success rates for a minute. According to Burke, the break-even success rate to make the decision to go for it correct in terms of Expected Points Added was 47%, but the break-even rate as far as Win Probability Added was 35%. What does that mean in English? That even if going for it in normal situations early in the game wouldn’t be wise, trailing by 8 with only 18 minutes left at your opponent’s 16 is one of those situations where you go for it even if it’s a close call. Now considering most of us would argue that a team like San Francisco should go for it on the first drive of the game facing 4th-and-2 at the 16, it becomes blatantly obvious that you do so when down by 8 with 18 minutes left. According to Burke, this dropped San Francisco’s win probability from 30% (if they went for it) to 26% by kicking. Throw in David Akers’ struggles, and it becomes a slam dunk decision to go for it. Had Akers missed the kick, Harbaugh never would have forgiven himself for this bad call.

Why was this decision by Harbaugh so poor? I opened up my Fourth and Harbaugh post with this line:

In most playoff games, each coach is faced with a critical fourth down decision. Often times the conservative coach delays the decision to go for it in favorable circumstances early in the game only to be forced to do so in less optimal situations in the final minutes.

That turned out to be proficient, not because I am wise, but because Harbaugh was meek. The 49ers chose to kick a field goal on 4th-and-2 from the 16, trailing by 8. With two minutes left in the game, San Francisco faced 4th-and-5 from the 5-yard line, trailing by 5. By delaying the decision to go for it earlier in the second half, Harbaugh was forced to go for it in a much more difficult situation at the end of the game: his team failed, and subsequently lost the Super Bowl.

One final note: this was a clear case of Harbaugh being too conservative. That is fundamentally different than the failure to go for two when down by 22 (before the touchdown), which was just wrong. Going for 2 down by 22 has nothing to do with being aggressive and everything to do with probability. That said, I think this decision to kick the field goal was the bigger mistake as far as hurting his team’s chances to win.

Now, for a brief interlude, let’s look at where John went wrong and Jim went right.

4th and goal from the 1

With 13:30 left in the 4th quarter, the Ravens led by 5 points. They had 2nd-and-goal from the 1-yard line, and ran Ray Rice to the left for no gain. On third down, they rolled Flacco out to the right; he couldn’t find an open receiver, narrowly avoided a sack, and threw out of bounds. On 4th and 1, with 12:57 remaining, Justin Tucker was sent in for a chip shot field goal.

Going for it on 4th-and-goal from the 1 is such a significantly better option that it’s easier to think of the few times when it’s not the right call. Like say, down by 2, with three seconds left. Because in the vast majority of cases, going for it is the right call.

If the Ravens converted, they would be in the enviable position of leading by 12 (and they would likely go for two, possibly making it a 14-point game) in the fourth quarter. If they miss, San Francisco would be backed up on their own 1, and we just saw how conservative the 49ers were when they got the ball at their own 6. What does a field goal get you? An eight-point lead is a lot better than a 5-point lead, but at what cost? San Francisco took over at their own 24 yard line, and Colin Kaepernick scored a touchdown within four plays. In a high-scoring game, touchdowns are much more important than field goals, and forcing your opponent to be conservative because of field position becomes critical. The downside there was small, and if the Ravens lost the game, critics would rightfully wonder whether John Harbaugh cost his team the Super Bowl. And according to Brian Burke, Harbaugh made another error when he elected to kick a field goal on 4th and 2 instead of attempting to end the game with a first down.

The Challenge

The immediate reaction on twitter was that Jim Harbaugh made a poor decision to challenge a spot midway through the fourth quarter. On 2nd and 8, leading by two points at the Baltimore 38-yard line, Joe Flacco hit Anquan Boldin for a 7-yard pass that was ruled a first down. San Francisco had already burned one timeout, and losing another would have been a big blow. But I liked this call by Harbaugh for a few reasons. One, he hadn’t used any challenges yet, and the odds that he would need to use two more challenges between the 8-minute and 2-minute marks of the game are very low, so he doesn’t “lose” anything besides the timeout if he was wrong. Two, this had the chance to make a big impact: yes, Baltimore would likely convert on 3rd-and-1, but possession was huge in this game, and the ability to end a Ravens drive in their own territory with one stop by their defense represents a pretty big reward. Finally, it looked like there was a good chance the call would be reversed. As it turned out, the call was reversed, and Jim’s challenge looked to pay dividends when on 3rd and 1, Flacco dropped back to pass.

Originally, we can assume a run up the middle was called, but as the 49ers inched every free man they could into the box before the snap, Flacco audibled to a pass. The gamble worked, as he hit Anquan Boldin for 15 yards. This was an example of the Jimmy and Joes winning the battle, but Jim Harbaugh played this one as well as he could.

The Final Series

It’s tempting to want to rip Jim Harbaugh and Greg Roman for the final series, which admittedly seemed to make little sense. On 1st-and-goal from the 7, LaMichael James ran up the middle for two yards. On second-and-5, the 49ers called sprint right option — an unusual call for this 49ers team — and Corey Graham easily knocked the ball away from Michael Crabtree. The best play of the drive came on the next snap, when it looked like Colin Kaepernick might run in for a touchdown on a quarterback counter. Alas, with the play clock about to hit zero, Jim Harbaugh called timeout, and the 49ers were never able to use their best play (a flag was thrown, so if not for the timeout, the 49ers would have been charged with a delay of game penalty.) Instead, on the official third down, Kaepernick lined up under center and again threw to Crabtree; this time, Jimmy Smith collided with Crabtree and prevented the reception. Finally, on fourth down, the 49ers called every fan’s least favorite play, a lob to the end zone. Did Jimmy Smith hold Crabtree, preventing him from getting to the ball? Probably. But no flag was thrown, and the ball fell incomplete.

The Safety

It was hard not to smile at the brilliant execution by John Harbaugh’s team on the intentional safety. I was asked on twitter whether I thought an intentional safety made sense with 12 seconds left. My answer was no, because there would theoretically be enough time for the 49ers to get a good enough return to get into field goal range, or throw a Hail Mary where pass interference was called, setting them up to tie the game with a field goal.

This was an unusual call, but it’s happened at least four times before. [3]Bill Belichick famously called an intentional safety once, but the circumstances were much different. In fact, the 49ers pulled off this move against the Bengals in week 3 of the 2011 season. There, Andy Lee took a snap with 8 seconds left from his own 18, and used six seconds of clock on the safety. But the Ravens were on their own 8, and with 12 seconds remaining, you could envision a scenario where they might only drain three or four seconds off the clock, and San Francisco could have time for a short pass to set up a long field goal or Hail Mary following the free kick (if they chose to fair catch the free kick).

Instead, the 49ers looked woefully unprepared for this possibility, and punter Sam Koch was able to run eight seconds off the clock. For the former special teams coach, this must have been the icing on the cake, as the Ravens used some elbow grease to drain the clock. Harbaugh instructed his lineman to hold, since the penalty for holding in the end zone is only a safety. That would be a variation of an old tactic by Buddy Ryan called the Polish Goalline.

Execution

Jim Harbaugh made several strategical errors that hurt his team, but I’m not going to blame the loss on him. The 49ers had some bad penalties and wasted key timeouts, usually the sign of a poorly coached team. But I’m still not going to blame him for the loss. The Ravens did a good job bottling up the 49ers at key moments in the first half, and they were able to successfully convert in the red zone (2 of 4) and on third downs (9 of 16) while the 49ers could not (2 of 6 and 2 of 9, respectively). Even with those disadvantages, and even with losing the turnover battle, the 49ers might have won the game if they hadn’t let Jacoby Jones score a 108-yard touchdown. The Ravens performed better, and the players won the game. With neutral coaching, I think the Ravens win that game more often than not. But it’s fair to wonder whether Jim Harbaugh could have started his dynasty yesterday if he had been a little smarter — and more aggressive — in the second half of the Super Bowl.

References

| ↑1 | I’ll point out that there’s probably some benefit to this bad coaching, as it incentivized the 49ers to go for a touchdown on the final drive instead of playing for overtime. But I feel dirty doing so. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | I am excluding Matt Bosher’s “run” play, which was the result of a bad snap and not an actual (or intentional) two-point conversion attempt. For the same reason, I am excluding Adam Podlesh’s successful run. That was actually a designed fake, but it doesn’t fit the spirit of the question. |

| ↑3 | Bill Belichick famously called an intentional safety once, but the circumstances were much different. |