Let’s review the passing games of the 2001 Raiders and the 2018 Raiders. Both teams were coached by Jon Gruden and had similar passing yardage totals: the 2018 Raiders gained 4,057 receiving yards (i.e., gross passing yards before deducting sack yards lost), while the 2001 version gained 3,862 receiving yards. But how those passing offenses were constructed were very different. [1]It is noteworthy, but not the intent of this post, that the 2001 Raiders passing offense was also much better. Oakland ranked 4th in passing yards in 2001, and more notably, 4th in ANY/A. The 2018 … Continue reading

In 2001, Gruden’s offense was largely centered around the team’s two top wide receivers, a pass-catching running back, and a tight end, in that order: Tim Brown had 1,165 receiving yards, Jerry Rice had 1,139, Charlie Garner gained 578 yards, and Roland Williams gained 298 yards. Brown and Rice combined for 60% of the team’s receiving yards, and the quartet gained 82% of Oakland’s passing yards. Jerry Porter, the team’s third wide receiver, was limited to 220 receiving yards, while fullback Jon Ritchie (154) was the only other player with 100 receiving yards. That did not stand out as unusual for the era.

The 2018 Raiders distributed the football in a very different manner. TE Jared Cook (896 yards) led the team in receiving, WR Jordy Nelson (739) was second, and RB Jalen Richard (607) was third… followed by three more wide receivers (Seth Roberts, Amari Cooper, Martavis Bryant) all topped 250 yards. Cooper was traded in midseason, of course, but the next two leaders in receiving yards were also wide receivers (Marcell Ateman and Brandon LaFell). The team’s top two wide receivers combined for only 30% of the team’s receiving yards, and the WR1-WR2-RB1-TE1 had only 67% of the team’s passing game.

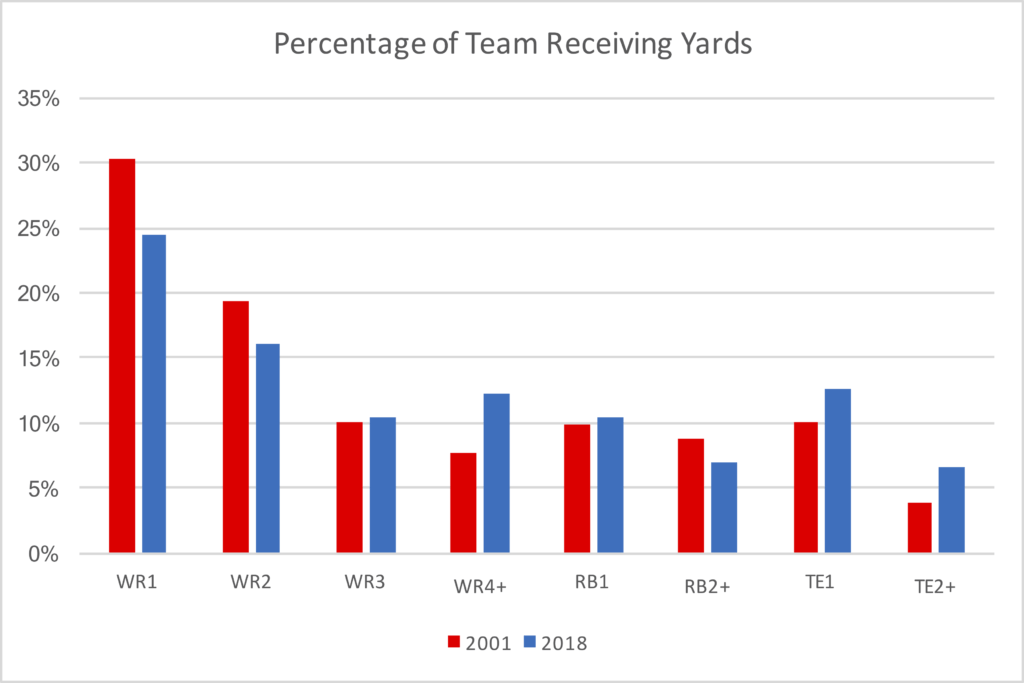

The 2001 Raiders were more centered around its top two wide receivers, while the 2018 Raiders were more focused on the backup receiving options and the tight end. And while this is just one extreme example, that description is representative of broader trends throughout the NFL. Consider:

- In 2001, the average team saw its WR1 and WR2 (in all cases, as measured by receiving yards) gain about 50% of the team’s total passing yards. That number dropped down to about 40% in 2018.

- In 2001, tight ends gained 14% of team receiving yards; that jumped to 19% in 2018, with similar increase for both TE1 and the team’s other tight ends.

- In 2001, WR4, WR5, WR6 (and so on) were end-of-the-roster type players who played special teams and rarely saw the field on offense. They gained about 8% of receiving yards, and 7 of 31 teams saw these players pick up 3% or less of their receiving yards. In 2018, that number jumped to over 12%, and 17 of the 32 teams saw these players gain over 13% of their team’s receiving yards.

The graph below shows the average percentage of receiving yards that went to the WR1, WR2, WR3, WR4+, RB1, RB2+, TE1, and TE2+ for the NFL in both 2001 and 2018.

It’s interesting that the production for WR3 hasn’t changed, even as teams go to more 11 personnel. That may be a reflection of injuries, or that teams (more?) frequently rotate their wide receivers. But my biggest takeaway is that the backup TE and the end-of-roster wide receivers have jumped from just 12% of the passing attack to 19% of the passing game. Part of that is the elimination of the fullback (and you can see a notable decline in RB2+ receiving yards since 2001) from many offenses, but it also represents a move away from the star wide receiver. Of course, as short passes to slot receivers and tight ends replace running plays, that naturally will show a more diverse passing game. [2]Idea for a future post: Given that teams pass more frequently now, and the passing pie has grown, have top outside wide receivers *actually* seen a decrease in the pie? Or is it that they are now … Continue reading

It’s interesting that the production for WR3 hasn’t changed, even as teams go to more 11 personnel. That may be a reflection of injuries, or that teams (more?) frequently rotate their wide receivers. But my biggest takeaway is that the backup TE and the end-of-roster wide receivers have jumped from just 12% of the passing attack to 19% of the passing game. Part of that is the elimination of the fullback (and you can see a notable decline in RB2+ receiving yards since 2001) from many offenses, but it also represents a move away from the star wide receiver. Of course, as short passes to slot receivers and tight ends replace running plays, that naturally will show a more diverse passing game. [2]Idea for a future post: Given that teams pass more frequently now, and the passing pie has grown, have top outside wide receivers *actually* seen a decrease in the pie? Or is it that they are now … Continue reading

There were 9 teams in 2018 where the WR4+ and TE2+ group actually outgained the number 1 wide receiver. This was most notable on the 2018 Dolphins, Redskins, and Cowboys. That happened just once in 2001: That was for the 2001 Bengals, who possessed one of the worst passing offenses in the NFL but also had — as their WR3 and WR5 — Chad Johnson and T.J. Houshmandzadeh. The idea that the production of your backups could outproduce your top wide receiver in the passing game across a number of teams is a new one.

Of course, I didn’t pick these years at random: if you look at the main chart in yesterday’s post, 2001 was a high-water mark for passing concentration in the modern era, and 2018 was the lowest mark. But while every year isn’t that extreme, the general trends fairly describe what’s happened to the average passing offense over the last two decades.

What stands out to you? Below is the full data set for each offense:

References

| ↑1 | It is noteworthy, but not the intent of this post, that the 2001 Raiders passing offense was also much better. Oakland ranked 4th in passing yards in 2001, and more notably, 4th in ANY/A. The 2018 Raiders ranked 20th in passing yards and 18th in ANY/A. Of course, it says a lot about the 2001 NFL vs. the 2018 NFL that the 2001 Raiders ranked much higher despite the 2018 Raiders actually gaining more yards. But this post is about breaking down how the receiving pie was broken up, not any of these other measures. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Idea for a future post: Given that teams pass more frequently now, and the passing pie has grown, have top outside wide receivers *actually* seen a decrease in the pie? Or is it that they are now just taking a smaller share of a bigger pie because of the short passes that replace the traditional running game? |