A few years ago, I looked at Eli Manning and the HOF in the context of an ANY/A Gray Ink test. What do I mean by that? Here’s what I did:

- Step 1) Calculate each quarterback’s ANY/A for each season of his career where he had enough pass attempts to qualify for the passing title (14 attempts per team game). ANY/A, of course, is calculated as follows: (Passing Yards + PassTDs * 20 – INTs * 45 – Sack Yards Lost) / (Pass Attempts + Sacks).

- Step 2) For each quarterback, award him 10 points if he led the league in ANY/A, 9 points if he finished 2nd, 8 points if he finished 3rd, … and 1 point if he finished 10th. A quarterback receives 0 points if he does not finish in the top 10 in ANY/A or does not have enough pass attempts to qualify.

- Step 3) For each quarterback, add his “points” from each season to produce a career grade.

I decided to update that post (written in 2014) and make a few changes.

1) I have included the results from the last four seasons.

2) I included sack data from 1960 to 1968, using estimated individual sack data based on team sack data.

3) I have lumped together the AAFC/AFL with the NFL in each season as if it was all one big league.

4) I have pro-rated the values based on the number of qualifying passers in each season. So let’s say a player ranks 4th in ANY/A in 2017, where there were 32 qualifying passers. He gets the average of 7 points and 7 points * 32 divided by 32, which is of course just 7 points. Now, let’s say a player ranks 4th in ANY/A in a 10-team league. He gets the average of 7 points and 7 points * 10/32 (2.18), which is 4.6 points. This is not a special formula, but a “good enough” metric that helps discredit players in smaller leagues, but not overly so (hence the average idea).

Okay, enough words. Here are the results. I have also included the raw totals, so you can see what happens if I didn’t pro-rate the values. Finally, I subjectively included some HOF labels at the end: actually in the HOF (not very subjective), Future HOFer, Borderline, and then either Not Eligible or a No for the HOF.

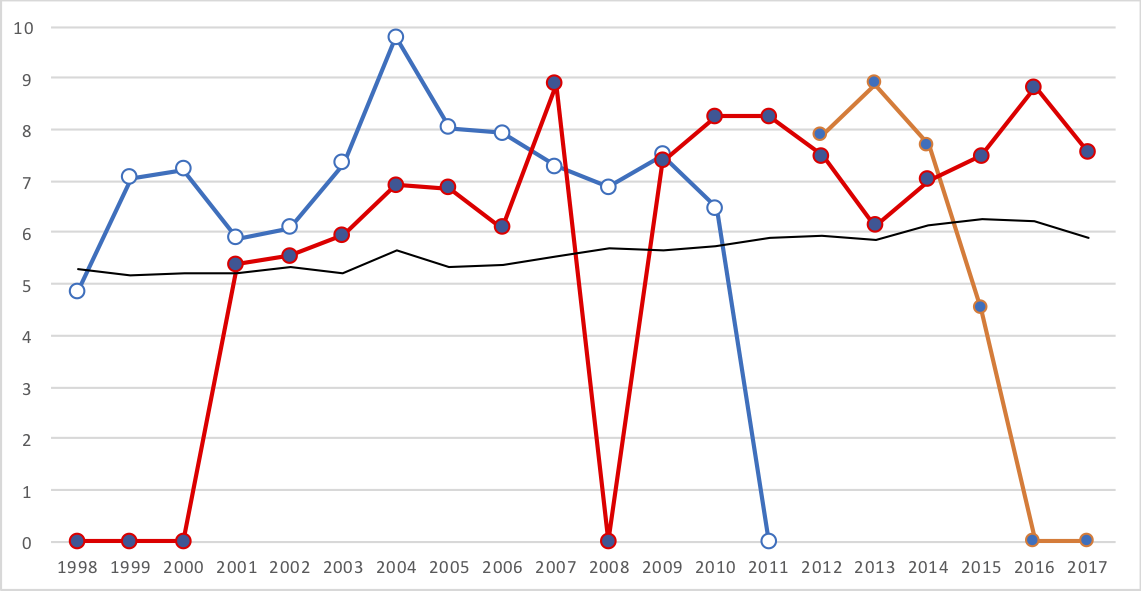

The future HOFers rank 1-4-5-13-18 by this litmus test: there’s not much to debate there.

Among the actual HOFers, only George Blanda — who is probably the least qualified quarterback of the “modern” era to make the HOF — ranks outside of the top 50. Bob Waterfield and Ken Stabler are the next lowest quarterbacks, and that’s consistent with how I’d view them. As a litmus test, this does a decent job for being a (somewhat) quick and dirty way to measure HOF play.

Among the Not Eligible guys, only Carson Palmer is in the top 60. He ranks 37th, on the back of a #1 season in 2015 with the Cardinals (+10.3 points, since there were 34 qualifying passers that year), a #3 season with the Bengals in 2005 (+8.25, also 34), and a 6th and 7th rankings in ’06 and ’14 (+5, +4.06). That’s not really a HOF career by any stretch, but it’s a memorable career.

Among the pure no guys — those who have been passed over and didn’t receive my subjective borderline label — you have Charlie Conerly at 26, Trent Green at 27, Boomer Esiason at 29, John Hadl at 31, Tommy Thompson at 33, and Milt Plum at 35. All good quarterbacks, occasionally great ones, who are HOVG (at worst) type players.

And then we get to the borderline guys. I gave 10 players that label, including three guys who entered the league in the last ten years and who are probably too young to really evaluate. Among the other 7…

Philip Rivers, Ken Anderson, and Tony Romo all are in the top 25, and make sense to be discussed together. None of the three won a Super Bowl, all three had fantastic efficiency numbers, and all three are more favored by the analytics crowd than the non-analytics crowd. Statistically, based on regular season efficiency, all three are clear HOF players. But, of course, that’s not the HOF test.

Steve McNair, Donovan McNabb, and Randall Cunningham are all borderline guys, too, and are underrated by an analysis like this that ignores rushing. They rank 68th, 72nd, and 104th. McNair (2003) and Cunningham (1998) each have a first place finish in ANY/A, while McNabb has a 2nd (2006) and 3rd (2004) place spot. McNair also has a 5th (2001) and a 9th (1999), while Cunningham has a 10th (1990), but that’s it, and that’s the problem. McNabb and McNair each have three finishes at 11 or 12 (worth zero) and McNabb has three more at 13/14; this analysis ignores solid seasons and rushing, which is going to hurt these guys a lot.

And then, of course, we get to Eli Manning. He was the inspiration for this post three years ago, and not much has changed since. Manning has a a 5th-place finish from 2011 (+6.1), and three 10th place finishes (2009, 2012, and 2015, each worth 1 point). He also has a 12th (2014) and a 13th (2010) place finish, but those are his only other top-15 seasons. Manning performs horribly in the ANY/A Gray Ink test for HOFers. He’s far behind Blanda, let alone the Stabler/Waterfield floor of quarterbacks.

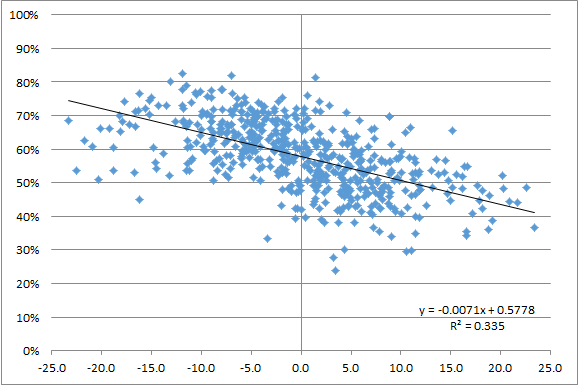

The graph below shows the data data but with color-coded labels: black for HOF or future HOFer,red for not in, orange for not eligible, and large green dots for the borderline guys. The running quarterbacks (McNair, McNabb, Cunningham, and Newton) are at the back of the pack with Manning (the second farthest dot to the right); the three “stats stars” are to the left, and then you have Ryan who currently ranks just outside of the top 40 (the X-Axis is rank; the Y-Axis is prorated value).

What do you guys think?