Brad Oremland is a longtime commenter and a fellow football historian. Brad is also a senior NFL writer at Sports Central. There are few who have given as much thought to the history of quarterbacks and quarterback ranking systems as Brad has over the years. What follows is Brad’s latest work on quarterback statistical production.

Best Statistical QBs of 2017

This is the third time in the last four years that I’ve written about my preferred stat for evaluating NFL quarterbacks, QB-TSP. In this post, you’ll find scores from the 2017 season, plus another way of using TSP.

If you’re not already familiar with the stat, I’d encourage you to read about how it works, but if you’re in a hurry, it is a purely statistical ranking, not my opinion. TSP measures production above replacement level, with “replacement level” defined as the level of play you’d expect from an available free agent (not your top backup). A good example last season was Jay Cutler, lured from retirement to play for Miami after Ryan Tannehill got hurt. Robert Griffin and Johnny Manziel didn’t play last season, but either one would have been a replacement player, as would an undrafted college senior. Anyone who you’re not sure whether or not they were still on a roster, like Kellen Clemens or Kellen Moore, is probably right around replacement level.

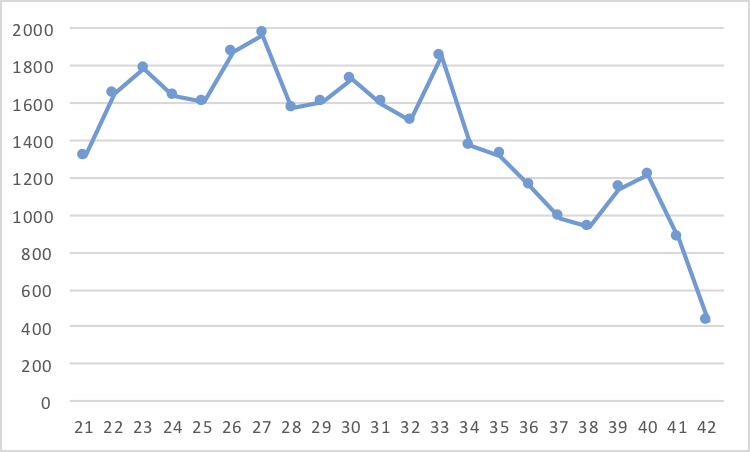

Here are rough explanations of single-season TSP and how it translates to Career Value:

* Zero TSP (0 CV) indicates replacement-level performance, on the fringe of being playable. 2017 example: Trevor Siemian.

* 500 TSP (0.3 CV) is an inconsequential season, an ineffective starter or a good part-time player. 2017 examples: Jacoby Brissett, Aaron Rodgers.

* 1000 TSP (1 CV) is an average season. The player had some value to his team, but he wasn’t a Pro Bowl-quality performer. 2017 examples: Blake Bortles, Dak Prescott.

* 1500 TSP (2 CV) is a good season, a top-10 season, a borderline Pro Bowl season. This is a positive contribution to any player’s résumé. 2017 examples: Ben Roethlisberger, Matthew Stafford.

* 2000 TSP (3.5 CV) is a great season. It’s a top-5 performance, the player almost always makes the Pro Bowl, and he’ll usually generate some all-pro support. 2017 examples: Alex Smith, Tom Brady.

* 2500 TSP (5.5 CV) is an exceptional season. These only occur about twice every three years. Most of them were first-team All-Pro, and about half were named league MVP. 2017 example: none. Matt Ryan in 2016 scored at this level, though.

* 3000 TSP (7.5 CV) is a legendary season, and the player always wins MVP. There have only been seven, the most recent being Peyton Manning in 2013 and Tom Brady in 2007.

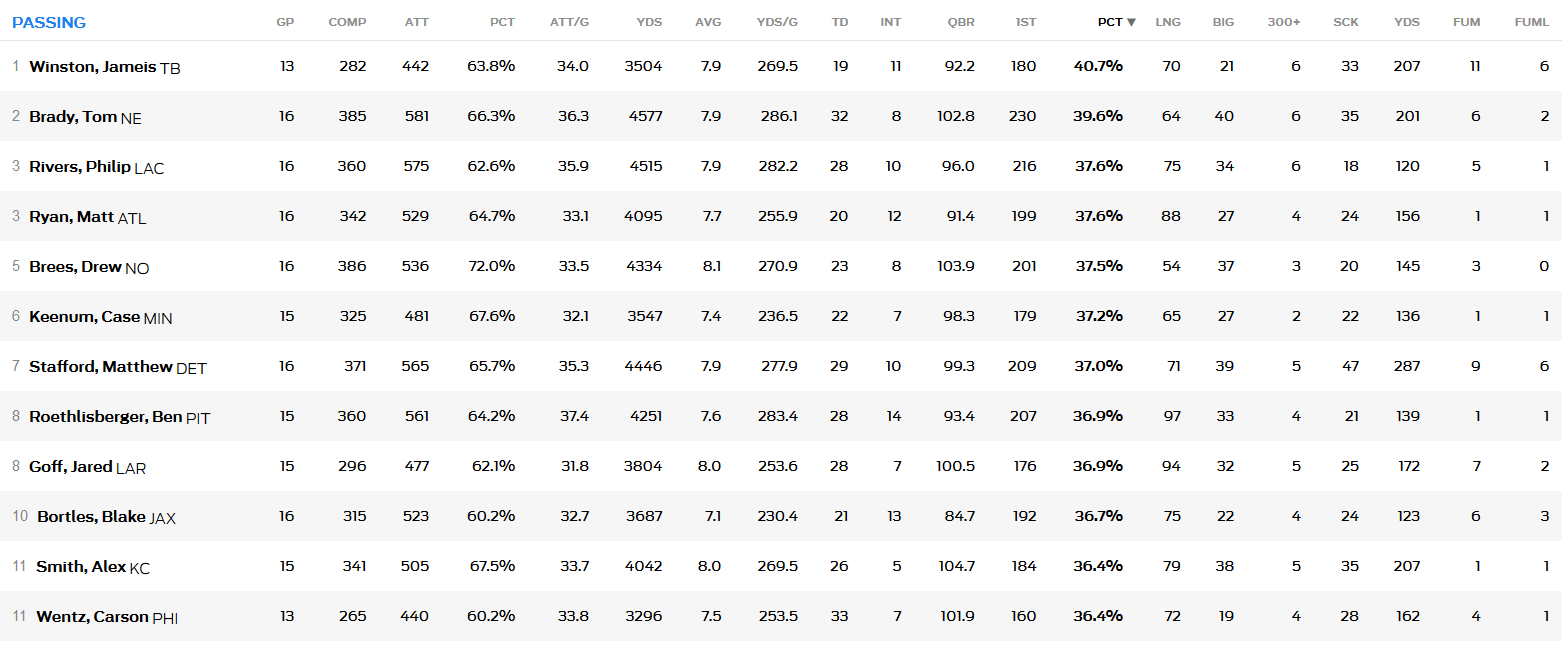

I’ll begin with raw data: QB-TSP for the top 40 in passing yards from the 2017 NFL season. The era-adjusted score, in the final column, is the one that aligns to the categories above. [continue reading…]